Cardiac arrest survival chances are improved by study

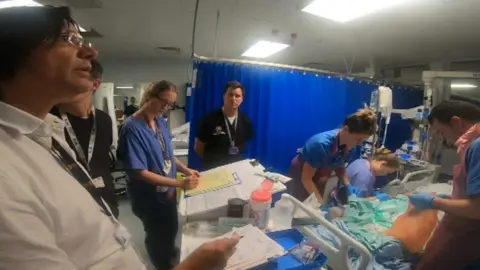

New research could transform the treatment of people whose hearts stop.

For more than 20 years, patients have been cooled to 33C (91F) when they arrive at hospital to try to increase survival chances.

But a new study has shown, so long as unconscious patients are prevented from developing a higher-than-normal temperature, any further cooling does not make a difference.

University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff supplied 54 patients for the study.

The study was the world's biggest cardiac arrest clinical trial, led by Sweden's Lund University.

"It's long been thought that cooling patients bodies after their hearts have stopped would improve survival and would improve their outcomes, but in fact this (study) suggests cooling to those low temperatures isn't helpful," said Dr Matt Morgan, who led the study in Wales.

The findings will help teams in intensive care departments focus on other treatments.

"Medicine is about doing things that work," Dr Morgan, an intensive care consultant, added.

"All you do by doing things that don't work is adding complications and the harms involved with them.

"It also means we can spend time doing the important things - nursing the patients, looking for the causes of the heart attack and caring for them in other ways."

Altogether 1,900 patients worldwide took part in the study.

Half were cooled down, often with pads containing cold water, to bring them down to 33C (91F) - our normal body temperature is 37.5C (99.5F) - and were kept like that for 28 hours, as well as getting the usual life-saving treatment.

The other half were kept at normal temperature - but not allowed to get hot either.

Results, which have now been published in the influential New England Journal of Medicine, show that hypothermia - when the body's temperature is below 35C (95F) - does not reduce death rates or recovery in unconscious patients with suspected cardiac arrest.

The trial presented challenges over consent because, in intensive care, people are often unconscious and their family traumatised.

So staff approached families about the study later, after the critical phase had passed - a process known as deferred consent.

Dr Morgan said this approach was vital to develop better treatments for the most seriously ill patients, and was keen to thank those who took part in this study.

One of the Welsh participants was Andrew Barnett, from Cardiff.

It was during a fathers and sons football match the week before Christmas 2018, with his seven-year-old son Seb, that he collapsed.

He led an active lifestyle and works for a sportswear company but did not know that he had a blocked artery.

"It was a usual day," he recalled, ahead of the game on Astroturf at Eastern Leisure Centre in Llanrumney.

"I'd worked from home and been for a swim at lunchtime and brought my son up for the game in the evening. I have very little recollection, only what I've been told by the people who were there.

"I don't remember the game at all or falling over. They grouped around me to see what was wrong but I was completely out so they knew it was something serious."

Family photo

Family photoLeisure centre duty manager Ben Clarke was in the office when he was told about Andrew's collapse.

"I grabbed the defibrillator from reception and ran out - as soon as I got there I could see he was not in a good way, he was unconscious," he said.

"I knew he'd gone - his heart had stopped. I started CPR - a colleague started unpacking the defib. I did four or five cycles of CPR and the machine showed he needed a shock. He was a grey-blue colour and it was clear he was dead."

The defibrillator also indicated he needed two more cycles of CPR - and Ben did this until Andrew started to show signs of life and the ambulance arrived.

When Andrew was admitted to the University Hospital of Wales, he was sedated and included in the trial - until he was taken off both the following day.

He cannot remember anything that happened the previous week - only waking up in the critical care unit the following morning.

"The first recollection I had was when they told me I'd had a cardiac arrest - I looked at the wall and I couldn't believe it, it was the sort of thing that happened to someone else."

About 6,000 people in Wales need resuscitating outside hospitals every year but only about 10% of these patients ever recover and leave hospital. Andrew is one of the lucky ones.

For Ben, it emphasised the importance of defibrillators being available in public places.

"It was good to know you'd helped save someone," he said.

"Me and Andrew have met up a couple of times for a drink - we've formed a friendship out of something which was negative."