Cardiff hospital trials cooling patients after cardiac arrest

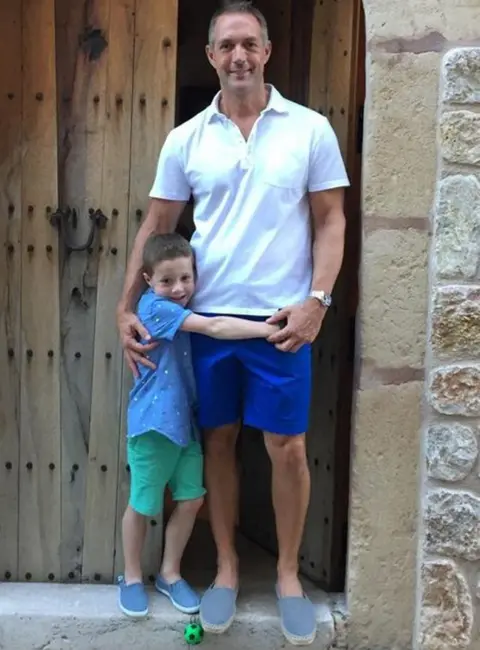

A year ago, Andrew Barnett collapsed and his heart stopped beating, as he played football with his young son.

Luckily, it was at on a pitch at a Cardiff leisure centre - which had a defibrillator - and the manager knew CPR techniques.

Andrew, 46, was revived and became part of a hospital trial to see if cooling the body in intensive care helps recovery.

The event was a complete blank but he realises how close to death he came.

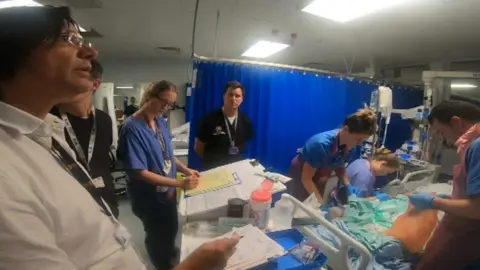

The cooling trial, involving nine UK hospitals, is being led by researchers at the University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff.

Altogether, 1,900 patients worldwide are part of the trial, called TTM2.

Half of patients were cooled down, often with pads and cold water, to bring them down to a temperature of 33C - our normal body temperature is 37.5C. They're kept like that for 24 hours, as well as getting all the usual life-saving treatment.

The other half are kept at normal temperature - but not allowed to get hot either - so the results can eventually be compared.

Dr Matt Morgan, intensive care consultant and researcher, is one of those leading the trial.

"It is looking at the importance of protecting the brain after someone suffers a cardiac arrest - and there have been theories since the 1960s of cooling the body to help protect the brain," said Dr Morgan.

"It's been used quite extensively in intensive care worldwide but what we really don't know is if that's truly beneficial."

'I couldn't believe it'

It was a during a "fathers and sons" football match the week before Christmas, with his seven-year-old son Seb, that Andrew collapsed.

He led an active lifestyle and works for a sportswear company but did not know that he had a blocked artery.

"It was a usual day," he recalled, ahead of the game on Astroturf at Eastern Leisure Centre in Llanrumney.

"I'd worked from home and been for a swim at lunchtime and brought my son up for the game in the evening. I have very little recollection, only what I've been told by the people who were there.

"I don't remember the game at all or falling over. They grouped around me to see what was wrong but I was completely out so they knew it was something serious."

Ben Clarke, leisure centre duty manager, was in the office when he was told about Andrew's collapse.

"I grabbed the defibrillator from reception and ran out - as soon as I got there I could see he was not in a good way, he was unconscious," he said.

"I knew he'd gone - his heart had stopped. I started CPR - a colleague started unpacking the defib. I did four or five cycles of CPR and the machine showed he needed a shock. He was a grey-blue colour and it was clear he was 'dead'".

The defibrillator also indicated he needed two more cycles of CPR - and Ben did this until Andrew started to show signs of life and the ambulance arrived.

When Andrew was admitted to the University Hospital of Wales, he was sedated and included in the trial - until he was taken off both the following day.

He cannot remember anything that happened the previous week - only waking up in the critical care unit the following morning.

"The first recollection I had was when they told me I'd had a cardiac arrest - I looked at the wall and I couldn't believe it, it was the sort of thing that happened to someone else."

About 6,000 people in Wales need resuscitating outside hospitals every year but only about 10% of these patients ever recover and leave hospital. Andrew is one of the lucky ones.

For Ben, it emphasised the importance of defibrillators being available in public places.

"It was good to know you'd helped save someone," he said. "Me and Andrew have met up a couple of times for a drink - we've formed a friendship out of something which was negative."

How is the UK involved?

The UK has contributed 392 of the 1,900 patients in the trial, which started in Sweden.

Hospitals taking part are:

- University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff

- Basildon University Hospital

- Birmingham University Hospital

- Bristol Royal Infirmary

- Manchester Royal Infirmary

- Queen Alexandra, Portsmouth

- Royal Berkshire, Reading

- Royal Bournemouth

- Royal Victoria, Belfast

How will patients find out if they are part of the trial?

The trial presents challenges over consent because, in intensive care, people are often unconscious and their family traumatised.

Staff will approach patients or families about the trial later, after the critical phase has passed.

But Dr Morgan is hoping they will understand the need to find out if the approach really is beneficial.

"We really, genuinely don't know what's best - that's why this trial is being done at all. If we did know best, there wouldn't be a trial."

Jade Cole, lead critical research nurse, said they looked at a range of criteria but patients needed to be have been revived for at least 20 minutes before they are appropriate for the trial. Patient safety and family wishes were a priority, she said.

"The family can veto what the patient would want because we don't want to upset a family in a very stressful situation," she said.

"I've done it hundreds of times but I've never had a patient unhappy about being involved in a research study - they have always been positive. They can be a bit shocked that you need to do research in intensive care."

Wales has contributed 54 patients to the trial, more than Germany or Italy. They're expecting the first results later this year.

Dr Matt Wise, lead UK investigator in the study and critical care consultant at UHW, added: "The risk of not conducting studies like this is that we'll carry on in many patients giving suboptimal or incorrect therapy.

"I remember talking at a conference in Brussels... and someone at the end asked me: If you have a cardiac arrest what temperature would you want to be? And I said - I'd want to be in the trial."

Family photo

Family photoAs for being part of the cooling trial, Andrew said he was "absolutely fine for that to happen".

"I went into casualty unconscious," he said. "It's key that patients going in become part of the process and non-consent because we all benefit from the medicine and the research that they're doing. It's also about how well you survive, so that's key as well."

He spent two weeks in hospital and had a further four months off work.

"I'm fine now - back to my normal work and day life. I'm back playing football with my son - training every Monday. You realise it can be taken away in an instance."