Bovril: A meaty staple's strange link to cult science fiction

Alamy

AlamyInvented to make beef last long journeys to market, Bovril became a famous British kitchen staple. Less well-known is its link to an odd, pioneering science fiction novel.

A stout black jar of Bovril with a cheery red top lurks in many a British kitchen, next to tins of treacle and boxes of tea. The gooey substance, made of rendered-down beef, salt and other ingredients, can be spread on toast or made into a hot drink, but what many people don't realise is that this old-fashioned comfort food has a surprising link to science fiction.

The "Bov" part of the name is easy enough to decipher – from "bovine", meaning associated with cattle. But the "vril" bit? That's a different story, literally.

In 1871, an anonymous novel was published about a race of super-humans living underground. The narrator of The Coming Race, who has fallen into their realm during a disastrous descent into a mine shaft, is shocked to learn that they are telepathic, thanks to the channeling of a mysterious energy called vril.

"Through vril conductors, they can exercise influence over minds, and bodies animal and vegetable, to an extent not surpassed in the romances of our mystics," the narrator realises. Vril gives them strength, as well, rendering them capable of incredible feats. The people call themselves the Vril-Ya, and their society seems in many ways superior to that of the surface dwellers. (Read more from the BBC about the weird aliens of early science fiction.)

Alamy

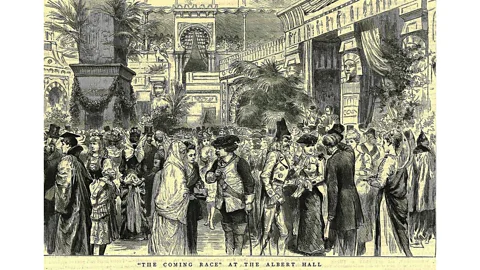

AlamyThe Coming Race was a runaway bestseller. It eventually became clear that the anonymous author was Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the prominent politician and writer (and, to give you a sense of his prose, the first person to start a novel: "It was a dark and stormy night…"). It became such a cultural touchstone that 20 years later, the Royal Albert Hall in London played host to the Vril-Ya Bazaar and Fete, to raise money for a school of massage "and electricity".

In 1895, a writer for The Guardian newspaper started a review of a new novel with this statement: "The influence of the author of The Coming Race is still powerful, and no year passes without the appearance of stories which describe the manners and customs of peoples in imaginary worlds, sometimes in the stars above, sometimes in the heart of unknown continents in Australia or at the Pole, and sometimes below the waters under the earth." The work under review? The Time Machine, by H G Wells.

And so you can see how, in the 1870s, when John Johnston, Scottish meat entrepreneur, was coming up with a name for his bottled beef extract, "vril" was a tip-of-the-tongue reference. Beef extract was not, on its own, a terribly compelling product. Johnston and other makers of the substance were responding to a demand for beef products in Europe, where raising cattle was prohibitively expensive, and the growth of cattle ranches in South America, Australia and Canada.

There was no way to get fresh meat from these far-flung places to Europe. But rendering the meat down into a paste and sealing it in jars yielded a shelf-stable product that could make the long journeys involved. (Johnston was not the only player in the meat extract game – Justus von Liebig, one of the founders of organic chemistry, founded Leibig's Extract of Meat Company to commercialise his process. The company later went on to produce Oxo bouillon cubes and Fray Bentos pies.)

How do you make a salty meat paste sound nourishing? By linking it to a fantastical substance with great powers. An excitable advert for Bovril in the program from the Vril-Ya Bazaar reads, "Bo-VRIL is the materialised ideal of the gifted author of 'The Coming Race'… it will exert a marvellous influence on the system, exhilarating without subsequent depression, and increasing the mental and physical vitality without taxing the digestive organs. It is a tonic as well as a food, and forms the most Perfect Nourishment known to Science."

The Coming Race has had a somewhat ominous afterlife. Members of the theosophy movement, including the spiritualist medium Madame Blavatsky, claimed that vril was real. Willy Ley, a German rocket enthusiast writing about conspiracy theories in Germany during the rise of the Nazis in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, said there was a society in Berlin that believed in vril: "They knew that the book was fiction, Bulwer-Lytton had used that device in order to be able to tell the truth about this 'power'.

"The subterranean humanity was nonsense, Vril was not. Possibly it had enabled the British, who kept it as a State secret, to amass their colonial empire."

Odd bedfellows, for a cup of meat tea.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.