What Western medicine can learn from the ancient history of psychedelics

Alamy

AlamyAfter more than 10,000 years of use, the ancient cultures and indigenous communities who use plant medicines may hold lessons for today's psychedelic Renaissance.

In a cave nestled into the rocky vastness of the Andes in south-west Bolivia, amid rubble and llama dung, in 2008 anthropologists discovered a small leather bag which had once belonged to a shaman from the Tiwanaku civilization – a pre-Columbian empire in the Southern Andes – more than 1,000 years ago. Inside, they found a collection of ancient drug paraphernalia. This included a snuffing tube, spatulas to crush the seeds of psychoactive plants and traces of chemicals ranging from cocaine to psilocin, one of the active hallucinogens within magic mushrooms, and the base ingredients of the psychoactive tea ayahuasca.

Experts believe that the shaman's bag represents a unique window into the relationship between ancient civilisations and powerful hallucinogenic drugs. The substances found within the bag are also of growing interest to today's medical researchers.

Psychedelics such as MDMA, LSD, psilocybin (another compound found in magic mushrooms) and ketamine have been gaining attention in the Western world as a possible way to tackle burgeoning mental health crises. Their proponents see some psychedelic compounds as a potential new class of blockbuster treatments for psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression and substance abuse, among others. It's thought that the compounds may help to alter the perspective of individuals with so-called "diseases of despair", including suicide, drug overdose and alcohol abuse, in conjunction with talking therapy. However, these treatments have also been criticised as over-hyped and potentially harmful.

As this emerging field of medicine develops – and not without many twists and turns in the road (see factbox: No MDMA for PTSD) – discoveries such as the shaman's bag in the Bolivian Andes are shedding light on the role psychedelics played in ancient societies. (Read more about how our ancestors coped with trauma.)

No MDMA for PTSD

Taking psychedelic drugs through the approvals process to become medicines takes a great deal of research.

On 10 August, the US Food and Drug Administration announced that it would not be approving MDMA-assisted therapy as a novel treatment paradigm for moderate to severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Some promising results from a Phase 3 trial had been published in September 2023, however the FDA said there was insufficient data to conclude that the drug was safe and effective.

Yet among these cultures, psychedelics were perceived in very different ways. Yuria Celidwen, a senior academic at the University of California, Berkeley says that the term "psychedelic" is very much a modern Western construct. Indigenous communities across the Global South have incorporated these drugs into their lives for centuries, referring to them as spirit medicines.

"The belief in the West is that they are used to treat mental health disturbances," says Celidwen, herself of indigenous Nahua and Maya descent, and who aims to use her research to reclaim, revitalise and transmit indigenous wisdom. "But indigenous use isn't only about rituals and ceremonies, but everyday practices. For example, if something of value had been lost, the community would go to the medicine practitioner."

Historical documents do indeed point to psychoactive substances being used for healing purposes, but this was just one small aspect of their use. Instead, spirit medicines played a major role in building connections within communities, sacred rituals, palliative care, exploring consciousness, facilitating creativity and hedonism.

Records show that the ancient Greeks and Romans held seasonal rites involving the ingestion of a psychoactive drug called kykeon which contained LSD-like hallucinogens. But Osiris Sinuhé González Romero, a researcher at Harvard University's Center for the Study of World Religions, who documents the history of indigenous knowledge, says that psychedelic use likely stretches back much further in human history.

Getty Images

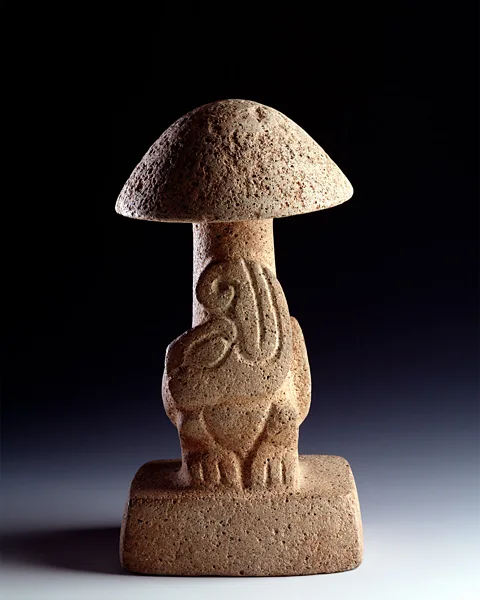

Getty ImagesArchaeologists believe that the psychoactive mushroom Amanita muscaria was first used in America sometime after humans first crossed the Bering Strait between eastern Russia and Alaska during the Ice Age around 16,500 years ago. The mushroom is still used today by the indigenous Ojibwa community in the Great Lakes region between Canada and the United States.

"We know that sacred mushrooms with psychoactive properties have an ancient tradition in Mesoamerica," says González Romero. "There's evidence of this from analysis of pollen, pictographic writing, ceramic sculptures of figurines holding sacred mushrooms, and even carved mushroom-shaped stones from the Mayan civilisation. It is thought that the use of the San Pedro and Peyote cacti [which both contain the psychedelic mescaline] goes as far back as 8,600BC in Peru and 14,000BC in Mexico."

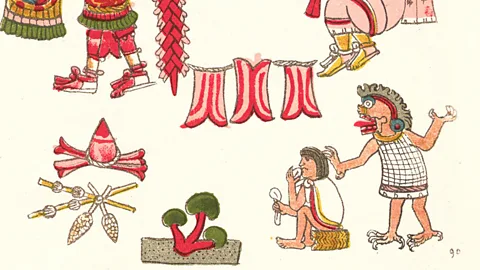

According to González Romero, one of the earliest known written documents describing a ritual involving sacred mushrooms is the Codex Vindobonensis.

Mexicanus 1, a pictorial book created by the ancient Mixtec civilisation – created by the indigenous Mesoamerican Mixtec people – between AD1100 and AD1521. According to the researchers Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez who have studied Mesoamerican Archeology and the Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1, one of the depictions features the God of the Wind carrying mushroom-holding lizards on his back, while participants in the ritual bear mushrooms in their hands.

Knowledge of these practices first began to be disseminated more widely through the writings of a Franciscan friar called Bernardino de Sahagún who spent decades studying and documenting the beliefs, culture and history of the Aztecs, following Spain's colonisation of Mexico. Albert Garcia-Romeu, professor in psychedelics and consciousness at Johns Hopkins University's School of Medicine, says that De Sahagún described Aztec rituals involving psilocybin-containing mushrooms in the 1520s, followed by what modern-day practitioners might call group therapy.

"He [de Sahagún] wrote that they would use these mushrooms in ceremonies where people would dance, sing and weep, and then in the morning, they would talk about their visions," says Garcia-Romeu.

But Celidwen says that for Western society to fully appreciate why indigenous communities have long valued these ceremonies and held these substances in such regard, it requires understanding the very different belief systems for interacting with and interpreting the world around them.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is growing interest within Western medicine in the use of psychedelics as a way of shifting perspective with the assistance of psychotherapy, helping people to process trauma and alteing the patterns of introspective thought which can take hold in conditions such as anxiety and depression.

However, Celidwen says that while psychedelic use in the West focuses on the individual, much of the use of psychoactive substances in ancient cultures across the Americas and the Global South has always been based around interacting with the natural and spirit worlds.

"In most of these traditional cultures, we don't have that sense of division between what is human and the natural world," Celidwen says. "We believe we are always interacting with living, responsive consciousness all around us, and when we use spirit medicines, we're looking for communication and to restore balance with that world. So the context is never individual wellbeing or mental health, but the collective wellbeing of the environment as a whole," she says.

Garcia-Romeu agrees, saying that among indigenous communities in Colombia, Brazil and Mexico, psychoactive substances are used to communicate with their ancestors, access other realms of being, and gain information about the world around them.

Having studied documents on Aztec medicine, González Romero has found that music, particularly drumming, has long played a role in psychedelic ceremonies as it reflects the beat of the heart, and is thought to aid a trance-like state which can facilitate creative expression. He explains that while we commonly use the word "shaman" to describe the practitioner who leads these ceremonies, this is a colonial concept. Instead, the term used by some indigenous communities directly translates as "the one who sings".

"Some alkaloids present in classically-used psychedelics, such as psilocybin mushrooms or LSA in the Rivea corymbosa plant, have psychodisleptic properties which means they cause auditive hallucinations or modifications in the auditory perceptions," says González Romero. "This means that even if you are not trained, you are able to create or hear music that has never been played for anybody in the world before. Perhaps because of this, in the Aztec worldview, mushrooms were seen as being related to Xochipilli, the god of song, music, joy, pleasure and fertility," he says.

These perceptions also extend to the way in which indigenous cultures viewed psychedelics for healing. González Romero says that the ritual could also involve fasting and sexual restriction for purification purposes, depending on what the practitioner deemed suitable for the patient. Some healing rituals would not involve music at all, but take place in complete silence during the night with domestic animals such as roosters and dogs locked away to avoid disturbances.

But while psychedelics could be used to treat anything from pain to fever, the emphasis was not so much on healing any one individual, but restoring balance to the community at large. "The Wixarika people have spoken about the Peyote cactus being used to bring their community back from anaemia after a big wave of malaria which depleted their population and health over 500 years ago," says Ahau Samuel, a practitioner of the Chicimeca tribe from Guanajuato, Mexico, who runs the plant medicine project Root of the Gods.

González Romero says that this is because some outbreaks of disease were perceived as being related to transgressions within the community, with the gods punishing the people by spreading illness. "The psychedelic rituals were a way of recovering the soul," he says. "The aetiology of indigenous medicines is very different. Some illnesses were seen as arising from a loss of balance between human beings and nature, for example a lack of respect from hunters killing more animals than they need and overexploiting the land," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGiven the long history of psychedelics in indigenous culture, many communities have mixed feelings about the recent boom in Western psychedelic research, spawning an industry which is expected to be worth $7bn (£5.3bn) by 2027.

Last year, Celidwen and a group of other researchers of indigenous backgrounds authored a paper where they raised concerns regarding cultural appropriation, exclusion of indigenous voices and leadership from the Western psychedelic field, and a lack of recognition of the fact that many of these substances are considered to have sacred value.

The authors of the study pointed out that while this burgeoning industry is built on medicines and practices which have been extracted and appropriated from indigenous culture, little of the wealth being generated by this multi-billion dollar industry is benefiting these communities. Reports suggest that while a place at a Western-organised psychedelic retreat might cost several thousand dollars, indigenous practitioners earn between $2 (£1.52) and $150 (£114.14) for performing similar services.

Others, including non-indigenous researchers, have questioned whether psychedelic medicines can achieve their stated goals of tackling mental health conditions, without in some way acknowledging the spiritual and mystical element of the psychedelic experience. Jules Evans, a psychedelics researcher at Queen Mary University of London, who directs the non-profit Challenging Psychedelic Experiences, explains that one of the reasons why adverse experiences can occur, is because they are so alien to our secular culture.

"Some indigenous American tribes have been using psychedelic plants for centuries," says Evans. "They have maps, guides, a deep familiarity with altered states of consciousness. Secular people, on the whole, do not. As a result, people can be bewildered by the experience and confused as to how to integrate it into a materialistic worldview. This existential confusion can last months or years, and the person who comes out on the other side may be very different to the person before," he says.

Celidwen says that one of the key limitations of the Western approach is that it focuses on psychedelic substances as akin to pills that can be patented. She says that if we can learn anything from the many thousands of years of use among ancient cultures, it is that the real power of psychedelics lies in their ability to encourage bonds between people and communities, as part of a collective experience.

"It's not the molecule itself, it is the larger constellation of relationships that are created that brings the healing," says Celidwen. "In the West, we often observe a peak of wellbeing right after the initial exposure to the medicine, but it isn't sustained because there is no collective context to the hallucinogenic experience. And because of that, you just risk creating another addiction because people keep going back to get the same sense of magic or wonder," she says.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.