The one simple change that will improve your media diet in 2024

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldWhere do you get your news? Here's how to deepen your understanding of current affairs – according to research.

Barely a month into 2024, it's difficult to know what shape the year will take. But one thing seems certain: politically, it's high-stakes. Elections will be held in the United States, Russia, Ukraine, Bangladesh, India, Taiwan, South Korea, and South Africa, for the European Parliament, and, many predict, in the UK too. That's not to mention the international conflicts in Israel-Gaza, Ukraine, and elsewhere, the climate crisis, explosion of AI, and economic challenges – among the other large-scale problems that require an informed and engaged public to help solve.

This means that it has, perhaps, never been more important to be a thoughtful, discerning citizen: no matter your country, you need a clear grasp of the world's issues – and of the policies put forward to solve them. People will never agree on the solutions, but surveys suggest most believe that a "good member of society" follows current affairs.

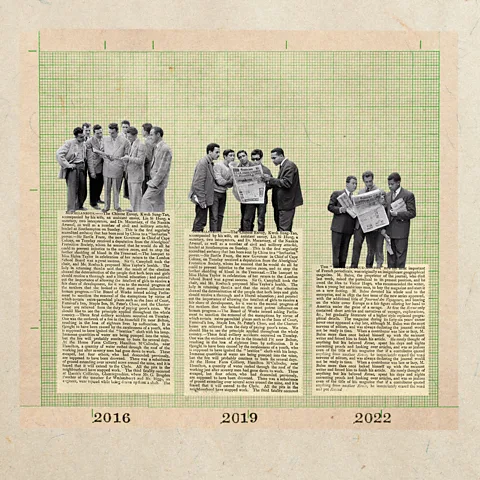

Yet by some measures, people's grasp of contemporary issues is fading. In the US, for example, recent polls have found that a shrinking share of adults say they follow the news closely – from 51% in 2016 to 38% in 2022. Among younger people, aged 18 to 29, it's just 19%.

It isn't just that citizens are tuning into traditional news media less. It's also that many are getting the news from elsewhere. Pew's polling has found, for example, that one in five US adults get their political news mainly from social media. And among those aged 18 to 29, it is nearly half.

Javier Hirschfeld/ Getty Images

Javier Hirschfeld/ Getty ImagesFacebook is the most common platform for news consumption in both the US and Europe, with one in three US adults getting news there regularly, compared to one in four on YouTube and one in six on Instagram and TikTok.

To be clear, social media can have benefits: it can be a source of support and community, for example, and help disseminate useful information, like public health guidelines. But in terms of informing people, there is a downside. Many assume that social media has made their fellow citizens more informed about current events. But research generally has found the opposite: the more time someone spends on social media, the less they know about politics and current affairs.

You're reading this on the BBC, so you could be forgiven for thinking we are simply blowing our own trumpet as a mainstream news provider. But I promise, there is evidence backing up these statements.

How Not To Be Manipulated

In today's onslaught of overwhelming information (and misinformation), it can be difficult to know who to trust. In this column, Amanda Ruggeri explores smart, thoughtful ways to navigate the noise. Drawing on insights from psychology, social science and media literacy, it offers practical advice, new ideas and evidence-based solutions for how to be a wiser, more discerning critical thinker.

The same 2020 Pew poll found that those US respondents who used social media the most, for example, were the least likely to correctly answer questions about topics in the news, like the Covid-19 pandemic and Donald Trump's impeachment. Only 17% of those who primarily got their news from social media had "high political knowledge", versus 45% who got their news from a news website or app.

Not only were the social media users less likely to know what was going on in the world – but they were more likely to have heard false, or unproven, claims and conspiracy theories. And they expressed less concern about these claims than other cohorts.

These findings have been backed up by other research. One study, for example, found that the more that participants used Facebook to consume and to share the news, the less political knowledge they had. Another found that every extra half hour of social media use reduced knowledge by about one correct answer out of an assessment of 16 questions.

Of course, it could be a chicken-and-egg situation. Perhaps people who are less interested in politics may be more likely to be on TikTok than (say) reading the BBC News app. And people have long decried the political disaffection of youth. (In one 1938 article I came across, an ex-provost bewailed "a flagging interest among young people in present-day politics" – caused, he said, by the distractions of "cinema" and "motor cars").

It's also important to remember that social media can offer numerous benefits when it comes to informing the public. For example, when major media outlets don't have the capacity, or access, to report what's happening on the ground, content shared by users who are there can fill huge gaps in knowledge. Take the Arab Spring: while the exact role of social media is still being debated, many academics agree that, particularly in countries where governments controlled media outlets, social media played a major role in sharing with the world what was happening. The same argument has been made about the Israel-Gaza war today. With international journalists' access into Gaza severely restricted, it is users on the ground (including Gazan journalists) who are sharing raw, unfiltered glimpses of life in the war zone through platforms like Instagram, TikTok and X (formerly Twitter).

Javier Hirschfeld

Javier HirschfeldBut social media has plenty of well-documented pitfalls, too. One is the potential tendency of social media platforms to create "filter bubbles": echo chambers helped along not only by like-minded communities of friends, but by ever-more-sophisticated algorithms that know your most intimately-held political opinions and push you similar content. Some research has found that this doesn't have as powerful as an effect as you might think – and even that social media users are exposed to a higher variety of media sources than traditional media users. But other experts disagree, and research has found that for highly divisive topics, in particular – like vaccines and abortion – users on platforms like Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) are more likely to see content that already aligns with their beliefs.

Algorithms often seem to reward more extreme ideological positions, and those with more extreme positions are most active on these platforms. On X, for example, users with extreme positions tweet more than more moderate users, while the majority of tweets are shared by a minority of extreme users.

Some of the social media firms have, under pressure, introduced labels or services that aim to stem misinformation. However, a lot of content is not vetted, fact-checked or verified, so these platforms have become common battlegrounds for forces of propaganda, disinformation and misinformation. Fake claims frequently go viral. Some even make their way into more mainstream media sources, like the recent false claim that a Palestinian baby killed by Israeli bombing was actually a doll, misinformation that was repeated (and later retracted) in a story by the Jerusalem Post.

You may also like:

So, if you're looking to be a smarter, better-informed citizen in 2024, should you avoid social media completely? Not necessarily. Like everything, it depends on how you use it. Given the research, I'd argue the best approach would be common-sense: limit your time on social media. Try to use it, primarily, for its original (if, today, somewhat archaic-seeming) purpose – keeping in touch with friends and forging new connections

As far as information-gathering on social media goes, make sure you are following reputable news outlets and journalists. Exercise caution with accounts and posts pushed your way by the algorithm. And, when you come across a news claim, always verify it before engaging.

In coming instalments, I'll describe other expert tips on how best to verify information – and much more. This is the first in a column about how to navigate the information (and misinformation) of today's world, drawing on psychology, social science and other evidence-based research.

In the meantime, here's to a smarter, wiser, and more discerning 2024.

*Amanda Ruggeri is an award-winning science and features journalist. She posts about expertise, media literacy and more on Instagram at @mandyruggeri.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.