Seaweed: Should we be eating more of it?

Getty Images

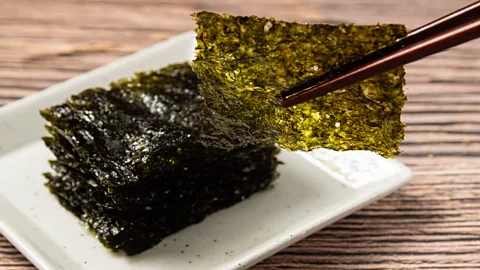

Getty ImagesSeaweed has long been a staple of many cultures, but the Western diet seems to have forgotten it. Is it a healthy ingredient we should be embracing?

Have you ever wondered why your homemade ice cream is covered in ice crystals, but shop-bought ice cream isn't? Or how onion rings are all the same size and taste like onion all the way around, when actual onions get smaller at the ends? Or how the beer you'd forgotten about still has a head on it half an hour later?

It's all thanks to seaweed extract, otherwise known as alginate, a natural fibre found in sea kelp, says Jeffrey Pearson, a professor of molecular physiology at Newcastle University in the UK.

While it's hidden in some foods in the West, whole seaweed is widely consumed in coastal parts of Asia. It's slowly becoming more well known in the West, and is being held up as a nutritional and sustainable "superfood". How true is that?

Some parents in the US have opted to replace fatty, salty crisps and other snacks for seemingly healthier dried seaweed as they have become more readily available. (Highly processed seaweed snacks can be high in salt and other additives and should be eaten in moderation.)

Other forms of seaweed can be low in calories, and packed with protein, fibre and polyphenols – which can lower the risk of heart disease, diabetes and some cancers – and can reduce blood pressure. It also contains iodine, which is important for thyroid function.

According to Pearson's recent findings, some species of seaweed may also help to control weight in people who are overweight or obese. This, he says, is because alginate inhibits lipase, an enzyme that helps the body digest fats – which means it can reduce the amount of fat digested from the diet by around 75%.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPearson and his researchers used an artificial gut to test the effectiveness of more than 60 natural fibres, by measuring how much fat was digested and absorbed when eaten with common foods including bread and yoghurt.

Pearson now plans to carry out clinical trials to see this effect when alginate is eaten as part of a normal diet. He hopes his research will lead to more alginate being cooked or baked into foods, such as bread, to help people manage their weight.

And it's not just weight loss that seaweed might help with. Large population studies in Japan have found a correlation between daily consumption of seaweed and lower rates of heart disease, compared with those who didn't eat any, and lower risk of stroke in men.

However, a recent review of 25 studies looked into the health benefits of eating seaweed. It found that many studies showing positive health outcomes correlating with a diet higher in seaweed carried out research on people who have health conditions such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, rather than the general population.

"In healthy individuals, it most likely won't breed any health benefits," says the paper's lead author, João Pedro Trigo.

Eating between 5g and 10g (0.1 to 0.3oz dry weight) of seaweed per day could, however, bring nutritional benefits from seaweed's fibre and nutritional content, Trigo adds. However, there is very little knowledge on how processing, such as fermentation, affects how seaweed's nutrients are absorbed by the body.

There are also some concerns around the potential risks of arsenic, lead and iodine found in seaweed. And some species of seaweed can contain more arsenic than others, says Florent Govaerts of the Norwegian food research institute Nofima.

"You can have the same species and one will contain a lot more arsenic than the other, depending on where it's produced," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe levels of arsenic in seaweed generally varies depending on the arsenic content in the water the seaweed is grown in.

But while there are real concerns around how much our diets can expose us to heavy metals, Alec Watt, director of macroalgae farm Green Ocean Farming in the UK, says all seaweed sold for human consumption is tested first.

"There are processes in place to check the seaweed," he says.

The type of arsenic seaweeds contain is the organic kind, which the body gets rid of in urine, says Pearson.

Seaweed can also contain high levels of iodine, but, again, the amount depends on the species of seaweed.

"You can get too much iodine if you eat too much seaweed," says Ingrid Undeland, a professor of food and nutrition science at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden.

"It's relatively small amounts before you hit the rough recommended daily intake. It also depends on the species and the potential presence of unwanted metals or elements in the water, which is a tricky message to convey," she says.

Too much iodine can lead to thyroid issues in some people, and more immediate side effects can include nausea and vomiting.

Also, studies have shown that several types of processing, including washing, blanching, boiling, soaking, drying, and fermentation, can reduce the amount of iodine in some seaweed species.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, there remains the small issue of taste. While seaweed extract doesn't taste of anything, Pearson says, he's tested participants' palettes with whole seaweed and found mixed results.

"We found that people either can't stand it, or they ask for more," he says.

Studies show that some people can be more sceptical of foods they're not familiar with. However, researchers have recently uncovered evidence that – contrary to popular belief – seaweed used to be a big part of ancient Europeans' diets during the transition to farming.

Researchers examined dental calculus from 74 individuals across Europe and found evidence that people ate seaweed during the Mesolithic Period around 8,000 years ago and into the Neolithic period 6,000 years ago.

"No one had found direct evidence of consumption of seaweed before prehistoric archaeological records. It was very unexpected," says Karen Hardy, co-author and professor of prehistoric archaeology at the University of Glasgow.

"We have preconceived ideas of what food is in Europe, and seaweed isn't the first thing that comes to mind," she says.

Perhaps, then, becoming accustomed to the taste of seaweed won't be that much of a challenge.

There may, however, be some confusion about how to actually eat seaweed and incorporate it more efficiently into our diets. Most seaweed we have access to in the UK and Europe is dried seaweed. Watt says that when rehydrated at home, the taste is affected.

"The difference between fresh and dried seaweed is as much as there between frozen garden peas and tinned marrowfat peas; they taste completely different," he says.

Watt recommends chopping up dried seaweed and sprinkling it into foods as a way to add seasoning. But while he's passionate about the benefits of seaweed, he's not optimistic about seeing frozen seaweed in supermarkets anytime soon.

"We need a celebrity chef to promote it," he says.

You might also like:

Despite seaweed's apparent communications issue, its reputation for having numerous health benefits prevails. When Govaerts carried out research to gauge people's knowledge and understanding of seaweed, he found that people in Norway and the UK generally have very little knowledge about seaweed, other than believing it's quite healthy, and sustainable.

But to make seaweed's messaging more complicated – it's not as simple as saying seaweed is healthy or unhealthy, safe or dangerous, researchers argue, because there are so many species.

Even in the UK and Europe, there are several species of seaweed growing for consumption, including ulva – otherwise known as sea lettuce – as well as sea spaghetti and red dulse, Watt says. Seaweed farming in Europe and the UK is primarily focused on kelp, though, because it's one of the hardiest species, and is quick to grow, says Watt.

Referring to all species of seaweed simply as "seaweed" is like referring to all vegetables as just a "vegetable", says Govaerts.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSeaweed species don't just vary in taste – their nutritional profiles are vastly different, too. And not only does the nutritional value of seaweed vary from one species to the next, but it varies depending on the water the seaweed is grown in, Undeland says.

"We should stop talking about 'seaweed', because they're so different in terms of how they relate to each other, and their contents. Some may be healthier than others and contain more proteins," says Undeland. "There are 145 species that are edible and six that are produced in mass quantity."

Whether seaweed – or certain species of seaweed – become more ingrained in the Western diet in the near future remains to be seen. There are still lots of unknowns regarding contamination of iodine and arsenic, however, seaweed's growing popularity is being taken into consideration by the European Food Safety Authority to better monitor this.

But celebrity chef or no celebrity chef, seaweed is associated with many health benefits, and could become a more widely and healthy addition to the Western diet. At the very least, it will no doubt continue to put homemade ice cream to shame.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.