Tyrian purple: The lost ancient pigment that was more valuable than gold

Alamy

AlamyFor millennia, Tyrian purple was the most valuable colour on the planet. Then the recipe to make it was lost. By piecing together ancient clues, could one man bring it back?

At first, they just looked like stains. It was 2002 at the site of Qatna – a ruined palace at the edge of the Syrian desert, on the shores of a long-vanished lake. Over three millennia after it was abandoned, a team of archaeologists had been granted permission to investigate – and they were on the hunt for the royal tomb.

After navigating through large hallways and narrow corridors, down crumbling steps, they came across a deep shaft. On one side were two identical statues guarding a sealed door: they had found it. Inside was a hoard of ancient wonders – 2,000 objects, including jewellery and a large golden hand. But there were also some intriguing dark patches on the ground. They sent a sample for testing – eventually separating out a vivid purple layer from the dust and muck.

The researchers had uncovered one of the most legendary commodities in the ancient world. This precious product forged empires, felled kings, and cemented the power of generations of global rulers. The Egyptian Queen Cleopatra was so obsessed with it, she even used it for the sails of her boat, while some Roman emperors decreed that anyone caught wearing it – other than them – would be sentenced to death.

That invention was Tyrian purple, otherwise known as shellfish purple. But though this noble pigment was the most expensive product in antiquity – worth more than three times its weight in gold, according to a Roman edict issued in 301 AD – no one living today knows how to make it. By the 15th Century, the elaborate recipes to extract and process the dye had been lost.

But why did this alluring colour disappear? And can it be resurrected?

In a small garden hut in north-eastern Tunisia, just a short distance from what was once the Phoenician city of Carthage, one man has spent most of the last 16 years smashing up sea snails – attempting to coax their entrails into something resembling Tyrian purple.

Alamy

AlamyA fishy empire

Tyrian purple was paraded by the most privileged in society for millennia – a symbol of strength, sovereignty and money. Ancient authors are particular about the precise hue that was worthy of the name: a deep reddish-purple, like that of coagulated blood, tinged with black. Pliny the Elder described it as having a "shining appearance when held up to the light".

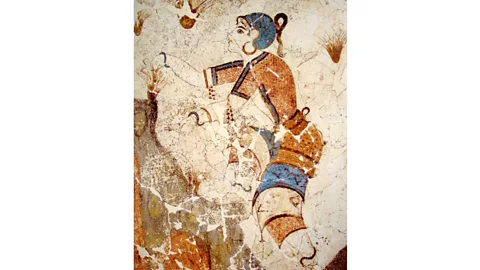

With its uniquely intense colour and resistance to fading, Tyrian purple was adored by ancient civilisations across Southern Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia. It was so central to the success of the Phoenicians it was named after their city-state Tyre, and they became known as the "purple people". The shade could be found on everything from cloaks to sails, paintings, furniture, plaster, wall paintings, jewellery and even burial shrouds.

In 40 AD, the king of Mauretania was killed in a surprise assassination in Rome, ordered by the emperor. Despite being a friend to the Romans, the unfortunate royal had caused grave offence when he strode into an amphitheatre to watch a gladiatorial match… wearing a purple robe. The jealous, insatiable lust that the colour ignited was sometimes compared to a kind of madness.

A slimy mystery

Oddly, the most celebrated pigment the world has known did not start life as a beautiful ultramarine gemstone, like its contemporary lapis lazuli – or a vibrant tangle of coral-pink roots, like the red dye madder. Instead, it began as a clear fluid produced by sea snails in the Murex family. More specifically, it was mucous.

Alamy

AlamyTyrian purple could be produced from the secretions of three species of sea snail, each of which made a different colour: Hexaplex trunculus (bluish purple), Bolinus brandaris (reddish purple), and Stramonita haemastoma (red).

Once snails had been collected, either by hand along rocky coastlines or with traps baited with other snails – Murex sea snails are predators – it was time to harvest the slime. In some places, the mucous gland was sliced it out using a specialised knife. One Roman author explained how the snail's gore would then ooze out of its wounds, "flowing out like tears", before being collected into mortars for grinding. Alternatively, smaller species could be crushed whole.

But this is the end of the certainty. Accounts of how colourless snail slime was transformed into the dye of legends are vague, contradictory and sometimes obviously mistaken – Aristotle said the mucous glands came from the throat of a "purple fish". To complicate matters further, the dyeing industry was highly secretive – each manufacturer had their own recipe, and these complex, multi-step formulas were closely guarded.

"The problem is that people did not write down the important tricks," says Maria Melo, a professor of conservation science at NOVA University of Lisbon, Portugal.

Mohammed Ghassen Nouira

Mohammed Ghassen NouiraA purple pong

In antiquity, Tyrian purple was not just renowned for its colour. Dyeworks were hotbeds of rotting fishy flesh with the added piquancy of urine – often used to help pigments stick. Whole neighbourhoods could become enveloped in this putrid aroma, and cities where it was manufactured were considered unpleasant places to live. The smell would permeate deep into the fibres of stained cloth, lingering long after it was purchased. Since the wealthy had exclusive access to this shade, it may have been advisable to stay upwind of them. (Read more from the BBC about the disgusting origins of the colour purple.)

The most detailed record comes from Pliny, who explained the process in the 1st Century AD. It went something like this: after isolating the mucous glands, they were salted and left to ferment for three days. Next came the cooking, which was done in tin or possibly lead pots on a "moderate" heat. This continued until the whole mixture had been boiled down to a fraction of its original volume. On the tenth day, the dye was tested by dipping in some fabric – if it emerged stained with the desired shade, it was ready.

Given that each snail only contained the tiniest amount of mucous, it could take some 10,000 to make just a single gram of dye. Mounds of billions of discarded sea snail shells have been reported in areas where it was once manufactured. In fact, the production of Tyrian purple has been described as the first chemical industry – and this not only applies to the scale of the operations, but their exacting nature.

You might also like:

"It is not really easy to obtain the colour," says Ioannis Karapanagiotis, a professor of conservation chemistry at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. He explains that Tyrian purple is totally unlike other dyes, where the raw material – such as leaves – contains the pigment already. Instead, the sea snail mucous contains chemicals which can be turned into a dye, but only under the right conditions. "It is quite amazing," he says. And yet, many crucial details of the process are long forgotten.

Alamy

AlamyAn abrupt decline

In the early hours of 29 May 1453, the Byzantine city of Constantinople was captured by the Ottomans. This was the end of the Eastern Roman Empire – and it took Tyrian purple with it.

At the time, the city's dyeworks were at the centre of the industry. The colour had become deeply bound to Catholicism – worn by cardinals and used to dye the pages of religious manuscripts. But it had already been suffering, after a succession of excessive taxes. Now the church had lost control of the pigment's production altogether. So, the pope soon decided that red would become the new symbol of Christian power. This could be made easily and cheaply by crushing scale insects.

However, there may also have been another factor in the demise of Tyrian purple. In 2003, scientists stumbled upon a pile of sea snail shells at the site of the ancient port of Andriake in southern Turkey. In all, they estimated that this garbage heap, dating to the 6th Century AD, contained around 300 cubic metres (10,594 cubic ft) of their remains – corresponding to up to 60 million individuals.

Intriguingly, though the bottom of the pile – where the snails were discarded first – contained some plump, older specimens, those discarded more recently were significantly smaller and younger. One explanation is that the sea snails had been overexploited and eventually, there just weren't any mature snails left. This may have led to the extinction of dye production in the area, the researchers suggest.

But just a few years after this discovery, another would raise hopes of reviving this ancient colour.

Mohammed Ghassen Nouira

Mohammed Ghassen NouiraA determined revival

One day in September 2007, Mohammed Ghassen Nouira was taking his usual lunchtime walk on a beach on the outskirts of the city of Tunis, Tunisia. "There had been a horrible storm the previous night, so there were a lot of dead creatures on the sand, like jellyfish, seaweeds, small crabs, molluscs," he says. Then he noticed a smear of colour – an intensely reddish-purple liquid was oozing out of a cracked sea snail.

Nouira, who works as a consulting manager, was immediately reminded of a story he had learned at school – the legend of Tyrian purple. He raced to the local harbour, where he found many more snails, exactly like the one on the beach. Their little spiral bodies are covered in spikes, so they often become trapped in fishermen's nets. "They hate them," he says. One man was plucking them out of his net and putting them in an old tomato can – which Nouira later took back to his apartment.

To begin with, Nouira's experiment was extremely disappointing. That night, he cracked the snails open and looked for the vivid purple entrails he had seen on the beach. But there was nothing there except pale flesh. He put it all in a bag to throw away, and went to bed. The next day, the bag's contents had undergone a transformation. "At that time, I had no clue that the purple was initially transparent – it's like water," he says.

Mohammed Ghassen Nouira

Mohammed Ghassen NouiraA modern application

Today scientists have been investigating a possible new use for Tyrian purple – or at least, one of the most important molecules involved. In its pure form, 6,6'-dibromoindigo is a deep purple powder, and it just so happens that it makes an excellent semiconductor – the basis of modern electronics. As an organic material it's biodegradable and less alien to the human body than silicon, so as well as making electronics more ecofriendly, it could potentially be used in wearable technologies. The best part? It can be made in a laboratory – with no sea snails involved.

Scientists now know that to jolt the chemicals in Murex snails out of their colourless state, they need to be exposed to visible light. Initially their secretions will turn yellow, then green, turquoise, blue and eventually a shade of purple, depending on the snail species. "If you do this process on a sunny day, it takes something like less than five minutes to have this transformation," says Karapanagiotis.

But this isn't instant Tyrian purple. The shade is actually made up of many different pigment molecules, all working together. Melo explains that there's indigo, which is blue, "brominated" indigo, which is purple, and indirubin, which is red. "Depending on the treatment of your extract, and on the dying, you can have very different colours," she says. Even once the desired colour has been achieved, there is still yet more processing to do to turn the pigments into a dye, such as converting them into forms that will stick to fabric.

For Nouira, this was the beginning of a 16-year obsession with uncovering the lost method for making Tyrian purple. Though others have investigated the secretions of sea snails before – including a scientist who processed 12,000 individuals into 1.4g of pure powdered pigment using industrial techniques – Nouira wanted to make it the old way, and rediscover the authentic shade that was venerated for millennia.

When he took those first sea snails in his apartment back in 2007, it was just a week after his honeymoon. "My wife was horrified by the by the smell; she almost kicked me out of the house… But I had to carry on," he says.

Mohammed Ghassen Nouira

Mohammed Ghassen NouiraIt took years for Nouira to make his first powdered dye, and when he did, it was a pale indigo colour, nothing like Tyrian purple and extremely dusty. Through years of trial and error, Nouira gradually discovered tricks that he suspects may have been used in antiquity – blending secretions from all three sea snail species mentioned in Pliny's account, adjusting the acidity of the mixture, alternating exposure to sunlight with darkness during preparation, and cooking his mixtures for different lengths of time.

For references, Nouira mostly used Byzantine mosaics depicting Justinian I and his wife Theodora – though he also later compared his results with surviving fragments of fabric. Eventually he ended up with pure pigments and dyes that he thinks are uncannily close to true Tyrian purple – and live up to the ancient hype. "It [the colour] is very alive, very dynamic," he says. "Depending on the light, it shifts and shimmers… it keeps changing and playing tricks on your eyes."

Mohammed Ghassen Nouira

Mohammed Ghassen NouiraAfter decades of pungent experiments in his shed, Nouira has been invited to display his pigments and dyed products at exhibitions all over the world, including the British Museum in London and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. He has also become something of a culinary expert on sea snail recipes; he recommends spicy Tunisian Murex pasta, or fried Murex. "It's crunchy, it's delicious, it's incredible," he says.

But Tyrian purple is again under threat. Today the challenge is not invasion, or secrecy surrounding how it's made – though like his ancient counterparts, Nouira is furtive about the exact details of his methods – but extinction. Murex sea snails are under threat from a barrage of human influences, including pollution and climate change. Stramonita haemastoma, which lends the colour a reddish tint, has already vanished from the eastern Mediterranean. So, whether or not Tyrian purple has finally been revived, one thing is certain: it could easily be lost all over again.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.