'I can't say my own name': The pain of language loss in families

Carolin Windel

Carolin WindelMithu Sanyal never learned her father's native language, Bengali, as a child. Is it too late to reclaim it?

Do you want to know a secret? A secret so shameful that I hid it for decades? It's only because of a chance conversation that I revealed it at all.

I was talking to a friend and colleague, Jacinta Nandi. She's an author, like me. Her father comes from northeastern India, like mine. Both of our fathers grew up speaking Bengali. Her father emigrated to England, and mine to Germany, where I grew up. Jacinta's father taught her a wealth of English puns – but, she says, "he never taught me a single word in Bengali". Like mine.

My father always spoke German to me. Of course I heard him speak Bengali: on the phone, or to the few Indian friends living in Germany. But I couldn't understand what he was saying. Even worse, my name, Mithu, is Bengali, but native Bengali speakers have told me that I don't pronounce it correctly.

Yes, that's right, I can't even say my own name.

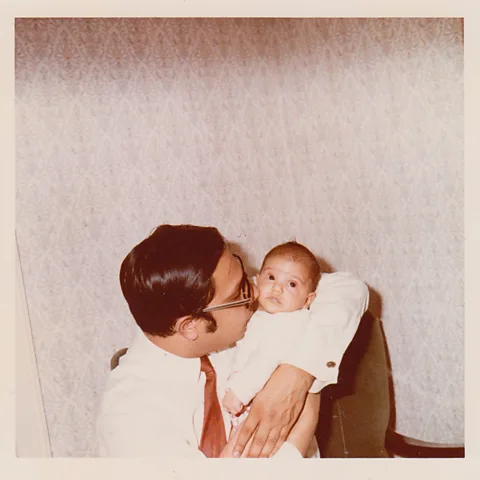

Mithu Sanyal

Mithu SanyalUp until my conversation with Jacinta I'd thought there was something seriously wrong with me. What kind of child doesn't learn their father's language?

Many of us, as it turns out.

Annick De Houwer is the director of the Harmonious Bilingualism Network and professor emerita of language acquisition and multilingualism at the University of Erfurt in Germany, and one of the world's leading experts on how and why some families lose their languages. In 2003, she published results from a survey of language use in 18,000 families in Flanders, a Dutch-speaking region of Belgium.

"I discovered how often it happens that bilingually raised children don't speak two languages," explains De Houwer, who is also the president of the International Association of the Study of Child Language. The survey and later studies by De Houwer and others across different countries and languages found that between 12% and 44% of children who grow up hearing two or more languages, actually end up speaking only one language. "Most babies start by learning words in both languages. But when they go to preschool they only continue with one. And why is that? Because suddenly there is only a focus on this one part of them and children soon sense that their other language is worthless. Worthless!"

Once I started thinking about it, I couldn't stop asking people how it felt not to be able to speak their family's language. Many opened up about feelings they'd bottled up all their life.

"My father was born in Lebanon but he spoke Arabic only on the phone or with visitors or in restaurants," says Andrea Karimé, a children's author and storyteller in Germany. "So as a child, I thought he was speaking a secret language. My father became a secret to me."

Emily Chowdhury, a Berlin-based artist, spoke of rejection: "When my parents discussed things we weren't supposed to hear, they switched to Bengali. Language was used to keep us out."

At the same time, and rather paradoxically, for those of us who inherited our ancestors' looks and names, there is often a wider social expectation that we would speak their language. When that is not the case, the reaction can be harsh. I love the poem "8 Confessions of My Tongue". The poet Noel Quiñones, who was born and raised in the US, describes the experience of having Puerto Rican ancestry yet not being fluent in Spanish: "My last name an invitation to strangers who say: your parents should have taught you". Or: you should have made more of an effort, as if toddlers put their fingers into their ears as soon as their parents speak Spanish. Among non-Spanish-speaking Latinos, there is a common experience of feeling ashamed or having their identity questioned over their language loss, research suggests.

I think of these lost languages as our "othertongues". They are present in our ancestry and childhood memories, and yet, strangely out of reach, because we never learned them ourselves, or were encouraged to forget.

In my case, there were actually two losses. I didn't learn my mother's native language, Polish, either. When I was growing up, my parents were warned against teaching me Bengali or Polish. They were told that if children learn more than one language simultaneously, they won't learn any of them properly. As if their languages might contaminate the "real" language – in this case, German.

"That's not a thing of the past, unfortunately," says De Houwer, referring to the long-disproven idea that bilingualism might hold children back, or confuse them. In fact, research has shown that bilingual children's speech is not delayed, and their tendency to sometimes mix their languages (known as code-switching, or translanguaging) does not mean they are confusing the two. Rather, it is a sign that they are using their dual vocabulary resourcefully, picking the most appropriate words for any given context.

Mithu Sanyal

Mithu SanyalMartha Bigelow, a professor for second language education at the University of Minnesota in the US, says there are still a lot of mistaken beliefs about language learning, "like it's better to not translanguage [mix languages], like it's better for some reason to know less than it is to know more". These beliefs have a concrete impact: "[In the United States] the advice is still that to learn English it's best to just speak English."

Even when it comes to second languages, there are clear distinctions in how society treats them. English is omnipresent in Germany, and considered desirable. My husband is British, and everybody speaks English to him even though his German is often better than their English. But other languages aren't welcomed in the same way. Turkish is one of the largest minority languages spoken in Germany, with a history that reaches back to labour migration from Turkey in the 1960s. And yet, Turkish speakers still face discrimination.

In 2020, a nine-year-old girl was reprimanded by her teacher for speaking Turkish to her friend in the playground of their school in Germany. As punishment, she was ordered to write an essay titled: "Why we speak German in school." The resulting essay included lines such as: "We are not allowed to speak our mother tongue. So that we improve our German". Her family made a formal complaint with the support of a lawyer, who questioned whether a child speaking English during breaktime would have been punished in the same way. There is a saying among Germans of Turkish ancestry: Turkish isn't a language you learn, Turkish is a language you forget as quickly as possible.

When my hometown in Germany, Düsseldorf, put up a street sign in Arabic as part of a celebration of multilingualism, it was smeared with racist graffiti, and attracted online comments demanding that "they" should learn German. While a street sign in Japanese that was put up at the same time was fine.

What explains this dramatic difference in how languages are valued?

Research suggests that it's often not about the languages at all – but about social attitudes, especially to immigration.

"[In Germany] immigration is still viewed as the exception to the rule, as not normal. Children who speak another language at home are seen as children who don't speak German at home," Mark Terkessidis, a well-known author in the field of migration and racism studies and member of the Academie der Künste der Welt, the academy of the arts of the world. "So when these kids come to school there's a focus on the deficit and not on the resource."

The resulting loss can have a profound impact on family relations. Parents may feel sad if their children do not speak their language. These feelings can go both ways. Janice Nakamura, professor of English at Kanagawa University in Japan, studied children in mixed families in Japan who could not speak the language of their non-Japanese parent. As adults, many felt angry with their parents. This is what Nakamura described as "language regret": the sense of a lost opportunity, because they didn't learn the other language.

De Houwer comments:. "So whichever way you put it, it's not good for family relations. It's really a very important thing to speak the languages of your parents: for the parents, for the children, for the family."

There are many things society can do to support this process, says De Houwer. One practical example is how multilingualism is treated in schools. "It is really necessary to actively – actively! – respect all the languages that children bring to the classroom and there are very simple ways of doing that. For instance, pronouncing a child's name correctly."

At this point in the interview I start crying, thinking of my own name and my inability to say it properly for so long. In De Houwer's view, such small steps could make a big difference, as could simply asking children how to say "hello" in the language they speak at home: "Important things like that. And then you can learn these," she continues. "And you can ask children to help you. And then all the children in the class are going to have to learn how to say hello to this new kid. To show an appreciation of all those different languages. It's a matter of paying attention to it. It's not a matter of money. It's a matter of changing attitude."

This appreciation, giving languages a more visible presence can also be helpful, says Bigelow. "It shouldn't just be a 'home language', it should be an 'everywhere language' that is legitimised in a lot of public spaces through language policies and signs in the streets."

On a personal level, there's of course one more way to fix language loss: by reclaiming the "othertongue" later in life. This can be a lot harder than it sounds.

Here is a recording of my dad trying to teach me a Bengali nursery rhyme, called "Ashmooli Pashmooli". Just to keep me on my toes, every time he translates it for me, the meaning seems to change a bit.

As an adult, I tried to learn Bengali again and again. And again. After years of effort, one of the few sentences I can say is: Ami Bangla tschiketschi. I'm learning Bengali. Which feels like a lie. The only thing I've learned is that it's simply too late for that now.

To my surprise, Bigelow disagrees. "It's not necessary to learn a language young. Younger is not always better." The so-called critical period of language-learning, during which we can learn to speak it fluently, is longer and more flexible than was previously thought, research suggests. Age is one of many factors that influence language-learning success, studies have shown, alongside other factors such as how much time you invest in learning the language, your motivation, and whether you have a community to share it with (Read BBC Future's previous report on age and language-learning.)

Bigelow also suggests being more flexible in how we view multilingualism: "You don't have to be perfectly fluent, or as fluent in all your languages as you are in your strongest one. We shouldn't hold the bar so high." For some, multilingualism may mean occasionally using words or phrases from one of the family's languages: "There are many ways of being multilingual."

De Houwer says that thinking about your needs can also help you choose the right learning strategy. "If there's an emotional need to connect with your family, or with your origin, or one part of your origin, then don't start your language journey by learning to read and write in that other language. Start with learning to talk and have conversations. You want to make friends."

This idea of connection resonates. I still feel the pain of not being able to read the books my father loved when he was a child. But I also feel joy whenever I hear Bengali, recognising it on the street even from a distance. I can love Bengali even though I'll never be able to speak it properly. I can find meaning in its special features, like the fact that Bengali nouns and pronouns have no gender – or all genders. And my favourite one: Bengali has six grammatical cases, and the fourth case is just for an unconditional present that you don't have to give back. This is what I hope all our othertongues will be one day: presents that are freely given and received.

--