Foresight: The mental talent that shaped the world

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen humanity acquired the ability to imagine the future, it changed the trajectory of our species. But in the age of the Anthropocene, we need to harness this mental skill now more than ever, say the scientists Thomas Suddendorf, Jon Redshaw and Adam Bulley.

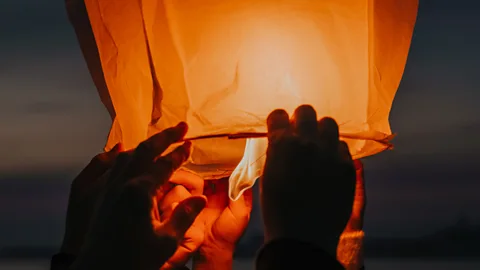

At the start of 2020, a mother and her two daughters in Krefeld, Germany, wrote New Year's wishes on six paper lanterns and let them fly. The sight of slowly-ascending sky lanterns, lit by candles inside, has beguiled people through the ages. Yet when this family were imagining their future, they did not anticipate what would happen later that night.

The lanterns drifted away, and eventually reached the ape house of the Krefeld Zoo. The flames inside the lanterns set the buildings alight – leaving dozens of primates, including two gorillas, five orangutans, and one chimpanzee, to die in the ensuing blaze.

Human foresight will never be 20:20. But this does not mean that we are doomed to repeat the mistakes of yesterday. We know we cannot foresee where our sky lanterns will land, and so it is for good reason they have been made illegal in so many countries.

Our minds can also recognise that many apparent human advances, motivated by our wishes for a brighter future, come with not-so-harmless consequences: forests are burning, glaciers are melting, and biodiversity is in decline. We are extracting what we want from the planet and leaving mountains of trash in return. Our litter can be found in the deepest sea trenches and the outer reaches of the atmosphere. Human activity, propelled by plots and plans, has impacted the planet so dramatically that scientists have declared a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene.

You may also like:

How did our capacity to think ahead (and its failings) get us to this point, and how might it show the way out of our troubles? Recently, we published a book called The Invention of Tomorrow that seeks answers to these questions, and more. It's about the remarkable skill of foresight in human beings, and all the ways it transformed the world for better and worse. When our hominin ancestors learnt to think about the future, it would prove to be a game-changer – and not just for us, but the planet too.

In Greek mythology, humanity gained their distinct powers when the figure Prometheus gave us a gift: fire from the heavens. There's no doubt that without flame, our species would never have flourished – but what's perhaps lesser known about the story is that the name Prometheus means foresight.

Alamy

AlamyOver the last two decades, research has established more and more facts about the cognitive and neurological basis of our capacity for "mental time travel": the ability to project the mind's eye into the past or future. It turns out that memory and foresight have many commonalities, and impairment in one tends to go hand in hand with impairment in the other. Children gradually acquire the ability to steer their mental time machines into past and future at around the same age, and in late adulthood memory and foresight also tend to decline in parallel.

But of course there are profound differences between past and future, not least the fact that the future is uncertain. One reason human foresight is so powerful is that we can think about multiple versions of what the future might be like, letting us compare our options and make better decisions in the present. Foresight is intimately bound up with what it means to be human – it is central to notions of moral responsibility, our deepest anxieties, and even our sense of free will.

The ability to think about the future can be traced back to the Pleistocene. We can see clues about our ancestors' advancing capacities in the form of carefully crafted stone tools and the remnants of firepits. Foreseeing what might lie ahead, they assembled stone-tipped spears knowing they'd later use them to kill from a distance, and crafted mobile containers that enabled them to ferry provisions to points in space and time.

Over the following millennia, humans increasingly set out to acquire skills and knowledge in advance, shaping themselves and their destiny. They noted the regularities of their world and innovated tools like calendars, money, and writing that dramatically improved their ability to coordinate future events. More and more people planted crops that would only be harvested months down the track.

Much later, the disciplined application of foresight in the scientific method became a key to ushering in the modern era. The scientific method essentially involves three steps. Data must be gathered via observation or experimentation, potential explanations for these data must be generated, and, finally, hypotheses must be derived from these explanations and put to the test. Foresight is integral to this process: scientists are in the business of making and testing predictions. If they are not consistently borne out, theories are replaced or amended.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesScientific thinking created new avenues for foreseeing the future – such as the tides or the weather. In the 1600s, Robert Hooke appreciated how science might be used to drastically improve human life. Hooke ventured that, one day, "we may be able to see the mutations of the weather at some distance before they approach us, and thereby, being able to predict and forewarn, many dangers may be prevented, and the good of mankind very much promoted".

With greater foresight, people also gained increasing control over the future, setting humans on a course of radical technological upheaval. Without it, we wouldn't have seen the Industrial Revolution – with its steam engines, coal mining techniques, and textile factories. The notion of an intimate relationship between science, technology, and "progress" quickly spread – as did pollution and poor working conditions, not to mention slavery, colonial exploitation, and warfare with ever more sophisticated arms. The innovations rolled on, bringing electricity, internal combustion, telecommunication, and, eventually, microchips, satellites, and weapons of mass destruction.

For better or worse, foresight has transformed the world. The population of Homo sapiens has exploded since the Industrial Revolution, from about one billion people 200 years ago to some eight times that figure now. We far outnumber all the other primates combined – great apes, small apes, monkeys, lemurs, and the rest. The mammals now most common on the planet are those we farm. (Read more from BBC Future about the debate over how many people the Earth can handle).

And our impact on Earth is not restricted to its organisms, with our split atoms, forged steel, and synthesised plastics. The combined weight of human material products (our buildings and roads, our computers and light bulbs, our trash) has been estimated at 30 trillion tonnes — or approximately 66,000,000,000,000,000lb.

That's not to say that farsighted scientific breakthroughs have not brought many benefits too. Thanks to advances in medicine, for example, as well as in related domains such as hygiene, safety, and public health, babies born today can expect to live about twice as long on average as those born merely a century ago. And visiting the doctor has typically become far less terrifying.

Imagine facing an operation without anything to dull the pain. Even kings and queens at any point bar the last 100 years or so would not have had the life expectancy that ordinary citizens of most countries have today. They would have suffered operations without anesthetics and died spluttering with common disease like everyone else. As recently as the 18th Century, five reigning European monarchs died from smallpox. Modern medical science has given humans new control over their own biology: the capability to heal injuries and cure diseases, and even to prevent problems before they arise.

Much of our apparent progress has been made possible by people foreseeing a better world, communicating about it, and cooperating to create it. Thinking ahead has played an essential role in human flourishing and has helped to bring us plenty we can be thankful for.

Foresight, though, is an imperfect skill.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe public arena is packed with leading figures failing to foresee what seems obvious in hindsight. Albert Einstein asserted in 1932 that "there is not the slightest indication that [nuclear] energy will ever be obtainable", whereas the president of the vacuum cleaner company Lewyt Corp foretold in 1955 that "nuclear-powered vacuum cleaners will probably be a reality in 10 years". The US postmaster general pronounced in 1959 that "before man reaches the Moon, mail will be delivered within hours from New York to California, to Britain, to India or Australia by guided missiles". And when humans did first land on the Moon, many people predicted there would be lunar colonies by the end of the century, with Venus and Mars ripe for further waves of colonisation. Few people foresaw what was actually going to transform much of our lives: innovations such as the internet and smartphones.

A failure to foresee can also have treacherous consequences. To smooth the operation of car engines, the inventor Thomas Midgley Jr introduced lead to gasoline, which he did not anticipate would turn out to produce one of the world's worst pollutants. Nor did he foresee that the CFC (chlorofluorocarbon) he introduced to refrigerators would be a major cause of ozone depletion. As one environmental historian once put it, Midgley "had more impact on the atmosphere than any other single organism in Earth history". Evidently, many of our innovative solutions to problems create new problems that require further solutions. Midgley's tragic story ended, true to his luck, when he was strangled by one of his own inventions (a pulley and rope system designed to help him out of bed).

Comment & Analysis

Parts of this essay were adapted from The Invention of Tomorrow: A Natural History of Foresight (Basic Books, 2022) by Thomas Suddendorf, Jon Redshaw and Adam Bulley

In many cases, the potential for disaster should have been easy to anticipate. The Krefeld Zoo sky lantern tragedy is unfortunately no anomaly. Take Balloonfest '86, when a charity organisation in Cleveland, Ohio, attempted to set a Guinness World Record by releasing 1.5 million helium-filled balloons into the sky. After six months of careful planning, thousands of people gathered on a Saturday afternoon to prepare for the spectacle. Local children excitedly filled and tied balloons for hours in the Sun until their fingers blistered.

Then, at around 14:00, the balloons were released in the public square to much fanfare. It seems unthinkable in hindsight that this stunt was allowed to go ahead – it's as if nobody involved could anticipate the now obvious consequences that were about to unfold. Soon, the city and surrounding areas were inundated by the descending garbage; thousands of balloons drifted onto the city airport's runway and grounded air traffic, while thousands more wreaked havoc on the roads. Two lost fishermen drowned when coast guard rescuers could not spot them among all the balloons bobbing around in Lake Erie.

Decades of shortsighted littering has left the world's waters teeming with ever more man-made materials. Anyone who reads the news in 2023 can no longer claim to be unaware of the environmental impact of humanity on nature.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo how might we put our foresight to better use?

Until the beginning of the 19th Century, people did not even realise that species could go extinct at all, let alone be driven to extinction by our own actions. As Elizabeth Kolbert relates, in spite of observations such as the disappearance of the dodo on Mauritius within a century of its discovery, the idea of extinctions was not properly established as a fact of life until the 1800s, when bones of the mastodon were discovered. These fossils represented a distinct species – too conspicuous to have been overlooked if they were still alive. Only by recognising the possibility of extinctions can we plan to avoid them.

Reducing our impact on nature calls for ever-more sophisticated forms of foresight. Rather than being driven by intuitions or emotional appeals about dolphins, pandas, tigers, and other charismatic species, we can now systematically analyse the predicted costs and benefits of alternative courses of action.

For example, consider our stewardship of the oceans. In 2010, the United Nations Strategic Plan for Biodiversity set a target to protect at least 10% of the world's oceans. But not all ocean waters are the same. Australia's waters, for instance, contain the largest reef system in the world, where some 600 types of corals have created some 3,000 reefs over 340,000 sq km (130,000 sq miles).

To respond to this problem, Australian researchers developed the Marxan algorithm – a scientific approach to spatial conservation planning – which has been used to rezone the Great Barrier Reef. This approach recognises diverse bioregions and the need to impose distinct "no-take" zones where fishing and other extractive activities are banned. It was a pioneering, large-scale, systematically-designed reserve system incorporating huge amounts of biological and economic data to boost conservation outcomes. Now over 120 countries have used this planning software.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUltimately, when we plot the future of our relationship with nature, much hinges on what we value and want to achieve, confronting us with tough moral decisions. Science might be able to help us look ahead, but it is up to us to choose which future to pursue.

We can also learn from our mistakes. After all, balloons are no longer allowed to be released for celebratory purposes in Cleveland, and the European Union finally outlawed single-use plastics in 2021. Every country in the world has stopped using leaded fuel, 100 years after Midgley introduced it.

Following the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer, people across the world phased out the use of the manufactured chemicals responsible – including Midgley's refrigerant – and managed to initiate a recovery. The ban on chlorofluorocarbons has been ratified by all countries, and consumption of ozone-depleting substances has fallen to less than 1% of what it was in the 1980s. (Read more about how we solved the world's ozone crisis.)

In light of the rapid increase in global temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions, the 2016 Paris Agreement commits governments the world to actions aimed at keeping global warming to below 2C compared to preindustrial levels.

These global efforts are extraordinary achievements in recognising our mistakes, exchanging our forecasts, and plotting a way out of our troubles. But even with widespread cooperation and commitments for tomorrow, averting future crises will require that our plans are enacted.

Human foresight is an incredibly powerful tool. By learning to better steer our mental time machines we can create a future worth looking forward to.

*Parts of this essay were adapted from The Invention of Tomorrow: A Natural History of Foresight (Basic Books, 2022) by Thomas Suddendorf, Jon Redshaw and Adam Bulley

--