Does kindness get in the way of success?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe've been taught that kind people don't have what it takes to be successful. But is this always the case?

We can probably all agree that it is good to be kind, moral to be kind, nice to be kind, but does it lead to success in life? After all, isn't kindness about putting other people's interests first? Doesn't it require self-sacrifice?

Yet consider these well-known people: James Timpson, boss of the Timpson chain of shoe repairers; Jacinda Ardern, the prime minister of New Zealand; and Gareth Southgate, one of the most successful managers that the England men's football team has ever had. All three of them are clearly "winners" in their fields, and yet all put kindness at the heart of their strategies for success.

What they have found is that taking a more compassionate and apparently "softer" approach to business, politics and sports management brings positive results, not just for the benefit of people who work for them, but for their own benefit too. The traditional notion that you have to be ruthless, driven and focussed on number one if you want to achieve success is being discredited.

You might also like:

There's a growing body of scientific evidence that kind people can be winners. In 2020 I was part of a team at the University of Sussex which carried out the biggest study of its kind on public attitudes to kindness. More than 60,000 people from 144 countries chose to fill in an extensive questionnaire called The Kindness Test which was launched on the radio shows I present – All in the Mind on BBC Radio 4 and Health Check on the BBC World Service.

When asked where people saw the most acts of kindness happening, the workplace did rather well, coming third after home and medical setting both as a place where people witnessed kind acts and where kindness was truly valued. So, a place that might have the reputation as cut-throat and impersonal, where people compete for positions, is home to more empathy and consideration than you might think.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWe do have to bear in mind that this was a self-selecting study, and at first sight, the results of a survey conducted by a branding consultancy of 1,500 people working in the UK were less positive, with only one in three respondents strongly agreeing that their immediate boss was kind, while a quarter considered the leader of their organisation to be unkind.

But dig a bit deeper into the results, and you find that respondents who did have kind bosses were more likely to say they would stay at their company for at least another year, that their team produced outstanding work and that their company was doing well financially. Meanwhile, 96% of the employees that took part in the survey said that being kind at work was important to them, suggesting that kindness at work does matter if an organisation wants to succeed.

This idea is backed up by research from Joe Folkman, a psychometrician based in the United States (psychometrics is a branch of psychology concerned with testing and measurement). He studied the 360-degree feedback ratings of more than 50,000 leaders and found the leaders rated by their staff as more likeable also tended to be rated highly on effectiveness. Perhaps more tellingly, scoring low on likeability and high on effectiveness was so rare that there was only a one-in-2000 chance of it happening. Folkman also found that the businesses with likeable leaders scored higher on a whole range of positive outcomes, including profitability and customer satisfaction.

It's notable that in the field of business research, kind leadership is more often referred to as "ethical" leadership, maybe because it sounds less soft. But whatever you decided to call it, studies have shown that it can result in a more positive atmosphere at work and that employees perform better too. Positive behaviour can cascade through the workplace, as seen in a study by the organisational psychologist Michelangelo Vianello from the University of Padua in Italy. He went to a public hospital near Padua and asked nurses questions about their managers, in confidence, including the extent to which they were fair and self-sacrificing and whether they stood up for the team. Where this was true, the nurses were more likely to report a desire to do something good for someone else, to be more like their boss or to become a better person.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere's evidence that even small acts of kindness and co-operation by anyone can make a difference in a workplace. Within psychology there is something known as "organisational citizenship behaviour". An example might be getting the printer mended, rather than leaving it broken for the next person to find, or watering the plants in the office. These actions aren't required as part of the job, but if we carry them out, the working environment is a little better for everyone.

They matter more than you might expect. In 2009, a researcher from the University of Arizona called Nathan Podsakoff synthesised the findings of more than a 150 different studies into a meta-analysis and the results were clear. These sorts of behaviours, though small in themselves, were associated with higher job performance, productivity, customer satisfaction and efficiency.

There's one arena in life where you might think there's no advantage in being kind and that's the dog-eat-dog world of politics. But even in politics there's evidence that a gentler or kinder style can still get you to the top, as Jacinda Ardern has shown in New Zealand. But what about more robust politicians such as Donald Trump? Doesn't his success show that a tough approach ultimately prevails?

Between 1996 and 2015, the academic Jeremy Frimer analysed the language used by members of the US Congress during floor debates. In his study, he showed that the approval ratings of congressmen and congresswomen went down when they were uncivil in their speeches in the House, and up if they were more polite and generous.

More recently, Frimer's team analysed reactions to Donald Trump's tweets (before he was banned) and they found that very few of his supporters actively "liked" his nastier tweets. The tweets didn't stop them supporting him, but they carried on doing so despite, not because, of, his incivility.

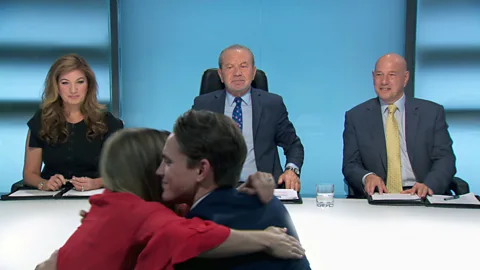

Of course, there are still plenty of examples of people who do well in life who are self-centred and unkind to others. But the point is that despite what we might see in The Apprentice or Succession, you don't have to be hard-nosed and obnoxious to get on in business or other highly competitive walks of life.

You can't be a winner simply through being kind of course – you need motivation, dedication and skill too – but there's more and more evidence that showing some kindness as you pursue your goal is no barrier to success.

--

Claudia Hammond is the author of The Keys to Kindness: How to be kinder to yourself, others and the world, published by Canongate.

--