The slave ship in a London courtyard

Tim Bowditch

Tim BowditchA new installation of 140 blocks of wood summons up a forgotten history, writes Melissa Chemam.

Laid out on the stone courtyard of London's Somerset House, like the fossilised remains of a whale, there is the outline of a slave ship. Made up of 140 blocks of charred wood, it is O Barco / The Boat by Grada Kilomba, a Portuguese writer and interdisciplinary artist of African descent (from Sao Tome and Angola). Forming the shape of the bottom of a boat, the piece references the slave ships that carried for centuries millions of Africans, enslaved by European empires. The blocks also contain poems in six different languages, inscribed on the surface. "Addressing the history of European maritime expansion and colonisation, the piece invites the audience to consider forgotten stories and identities," the curators explain; the civil administration responsible for the British Royal Navy was once based at Somerset House.

O Barco was originally created in 2021, and now appears in London, presented by Somerset House on the 10th anniversary of the 1-54 fair dedicated to contemporary African art. The artwork is accompanied by live performances made up of song, music and dance. "I would call it many things," Kilomba tells BBC Culture, "a sculpture, an installation, a performance and poetry. I'm not interested in one discipline in particular, but in telling stories… I first worked around the Greek myth of Antigone, a woman whose two brothers kill each other for power. The new king, Creon, allows only one to be buried in the city, while the other one is left to the dogs. To me, it became an important story about ceremony and memory, and human dignity."

Kilomba is also a lecturer, teaching post-colonial studies and psychoanalysis at institutions including the Free University of Berlin, Bielefeld University, and the University of Ghana. "The story of Antigone interrogates values that resonate, to me, with the stories of current humanity," she continues. "It asks: 'When are we respected bodies?' And 'Which communities are given the right to be treated as human?' Whether in London, Lisbon where I'm from, or Berlin, in Europe a history is being told that doesn't reflect the complexity of the reality of people who lived and survived the slave trade. The boat to me is a symbol of these times of glory, adventures and exploration that led Europe to exploit some humans for fabric wealth. I wanted to question what was inside these boats, and reflect on our societies' ghosts and traumas."

The ship's hold

Kilomba studied psychoanalysis and works "with the language of the unconscious" to bring a form of healing. Her goal is to invent both a language and physical forms to reflect questions she asked herself about her heritage, her society and the world around her. "I work through associations," she explains. "To me, it's become a natural process, where these human tragedies can be transformed into a visual language." She includes bodies, movements, music and rhythm into her performances, with, for this piece, music production by award-winning writer and musician Kalaf Epalanga. "The work is there to bring questions that weren't there before," Kilomba adds. "I work for creation and vision, not in the realm of morality".

Alamy

AlamyAsked how she relates today to the concepts around post-colonialism that she incorporated early, in the 1990s, in her writing and lectures, and how she reacts when the audiences decry these concepts, she first acknowledges the work of artists of many generations. "I don't feel like we're living a moment for black artists or black women artists or queer creators," she insists. "It's a problematic approach. Artists of our kind have been producing work for a very long time. Now, the hegemonic frame of the Western world sometimes made it a struggle for some people to understand our narratives, as our work is very futuristic. We live this timeless language, beyond the present, but also reconnecting to the past. The boat is about how the past and the present connect, that's what the pieces of wood represent, with the paint and the verses inscribed in different languages – Yoruba, Creole, Portuguese, English, Syrian Arabic…"

She works with symbols of repeated violence and tragedies, as a form of reflection on what it is to be human. "I'm very concerned by which stories can be told in public spaces," she says. "And my goal is to turn around knowledge, to inverse the notion of knowledge as known in Western civilisation, to include black people. The history of the slave trade and the 'Middle Passage' was for too long not represented in public places, and I want to show what happens when we don't want to remember that history."

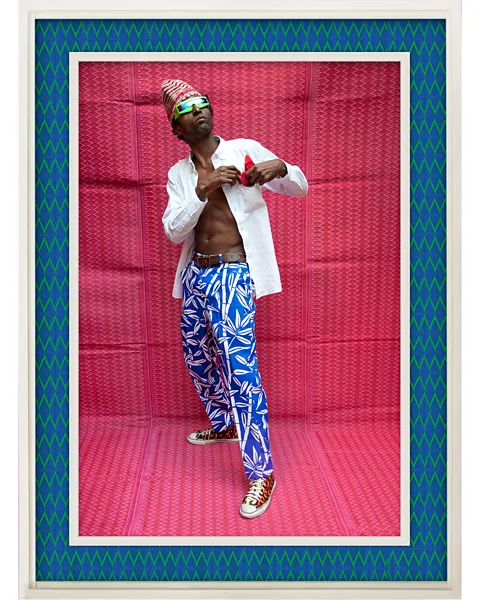

Hassan Hajjaj/Keziah Jones/ L'Atelier 21

Hassan Hajjaj/Keziah Jones/ L'Atelier 21Many African artists who have for long participated in the 1-54 fair work along similar lines. Nú Barreto, from Guinea Bissau, was one of the first artists to take part. His work on psychological wounds and African unity has since travelled around the world, notably his series of African flags titled Disunited States of Africa.

"Grada is a very interesting artist," he says, arguing that, "as artists and as Africans… we have some important questions to raise about our identities, often multiple. My work with the flags was political and through my art I continue to describe my story. And what touches the African continent touches me, even though I don't want to frame myself by the labels that are imposed on us, as nationalities or ethnicities. But as I'm an artist, it's my duty to look into these issues."

According to Barreto, the fair helps in empowering artists and gallery owners. The first 1-54 event enabled him to meet an international gallery owner, Nathalie Obadia, and since to exhibit in New York City, Brussels, Paris and recently Marseille.

Thierry Caron/Nú Barreto/Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris

Thierry Caron/Nú Barreto/Galerie Nathalie Obadia Paris"I can see that the different African blocs, lusophone [Portuguese-speaking], anglophone and francophone, evolve at different paces. The anglophone bloc is way ahead, thanks to artists from Nigeria and black artists in the UK and US."

In Britain, in recent years, the work of Keith Piper, Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce, Hew Locke, Chris Ofili or John Akomfrah, all of African or Caribbean heritage, have addressed similar issues, in their own ways. "What's important now is to remain united to push this progress forward on the continent itself," Barreto adds.

For Touria El Glaoui, the founder of 1-54 and daughter of Hassan El Glaoui, one of the most significant African modernist artists, the landscape of today for African artists has definitely changed for the better compared to 2011, when she launched her project. "We are in two different universes; the perception of the African artist has radically changed," she says. The fair also takes place every year in New York and Marrakesh, in Morocco, where Touria is from, with special events, panel discussions led by African curators, and solo shows for emerging artists.

"We're honoured to have Grada Kilomba this year, she's an artist of great ambition," Touria adds. "Her performance involves 27 people, creating with her the music, dancing and singing; it represents so much of what my project always aimed for. I believe artists can be stronger voices for these discussions on black and African history, each of them in different ways and different ideas, as Hassan Hajjaj, Julie Mehretu, Michael Armitage or Nú Barreto do. They offer some of the best ways to address complex issues and raise awareness."

O Barco / The Boat is at Somerset House, London until 20 October (accompanied by live musical performance at 5pm BST on 13 October and 1pm BST on 14 October). 1-54 London 2022 takes place until 16 October.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.