British Pop artist Peter Blake on his 'last necessary show'

Luke Andrew Walker

Luke Andrew WalkerFrom his iconic Beatles' Sgt Pepper cover to his latest sculptures created with found objects, the pioneering artist has always been ahead of the curve. He talks to BBC Culture about his life and work.

There are 50,000 items in Sir Peter Blake's studio, including a fleet of model galleons whose masts are a metre tall. He bought them at his local auction house, apparently because he felt sorry for them – "they're the epitome of bad taste, aren't they? No-one else was bidding".

For a good while afterwards, the pioneer of British Pop Art tells me, they "sat around here" amid the other collected and found objects, the creaking weaver birds' nests, the shells, dioramas, mummified "mermaids" and old signage, waiting for Blake's supple, unquenchable imagination to work its magic.

Courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot

Courtesy the artist and Waddington CustotAnd work it did: today the galleons have a second, far more meaningful life as sculptures, or 3D collages, their timber decks crawling with model figures engaged in battle. Knights vs "People being frightened in B movies", for example, and Farmers vs Punks. Now four of them set sail for Mayfair, where they will join some 50 other sculptures by Blake for an exhibition at Waddington Custot. He has never had a dedicated sculpture exhibition before, and considers it, he says, his "last necessary show".

We don't tend to think of Blake as a sculptor. A bold and bright painter, yes, and a voracious collagist. The creator of iconic record sleeves for bands including The Beatles and Oasis, and a sublime draughtsman – that too. But actually sculpture has been part of his practice all along.

One or two have appeared in shows where his paintings or collages played the starring role, and in 2003 he showed some at the London Institute (an outpost of the University of London), though the exhibition really centred – he tells me – on sculptures by 12 of his YBA (Young British Artist) buddies, to whom with characteristic generosity he had offered empty plinths. Gavin Turk and Mark Wallinger were among those to take up the invitation. Angus Fairhurst presented a banana. Or tried to – Blake accidentally snapped it during installation.

Now 91, Blake, who was elected to the Royal Academy in 1981, and knighted in 2002, hasn't been to his studio and cabinet of curiosities for about a year now. "I'd be dangerous," he says, peering over the tops of his spectacles. "I would definitely fall. My knees just give up and… yeah. It wouldn't be wise."

Courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot

Courtesy the artist and Waddington CustotWe have met instead at his home nearby. It's a lovely house, with dark-walled, marvel-filled rooms recessing into the distance. He lives with his second wife, Chrissy. The two have been married since 1987 and have a daughter, Rose. Blake also has two daughters from his previous marriage to artist Jann Haworth – Liberty and Daisy.

Blake, a little rumpled in his signature black suit and red braces, presides over a well-tended living room on the first floor. Even on a short January afternoon, it is awash with light. The radiators are set to equatorial.

He spent yesterday signing prints of a collage made "in the style of Peter Blake" by an AI robot – essentially a watercolour brush on a mechanical arm. It is a performance project, "curated" by Blake, in conjunction with Mandarin Oriental. "It can do a broad line or a tiny line," he says, sounding impressed. "It's exciting at this kind of extreme of life to be involved in the latest technology – a compliment in a way, but it won't be much use to me. I'd rather have a pencil."

We talk a little about AI – "clever, a bit frightening, I mean I have no idea how it works" – and whether he'll go to see the AI Elvis performing in London this autumn. After all, Blake once said that he wanted people to have the same emotional experience in front of his (many) paintings of Elvis as they would in front of the King himself. "Maybe," he says. "I'd be interested to see that."

More like this:

Blake's special connection to musicians is legendary. Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Chrissie Hynde and Roger Daltrey were among the parade of stars who helped mark his 80th birthday at the Royal Albert Hall. A decade later, his 90th birthday was marked with another celebratory concert at the Royal Festival Hall, curated by Paul Weller. He attributes it to a formula of friendship and hero-worship, "though with Paul Weller, the situation's sort of reversed. He's my hero, but I'm his hero as well. Robbie Williams and I were friends for a long time. I was most impressed with Brian Wilson. I love his work, you know. I love those songs."

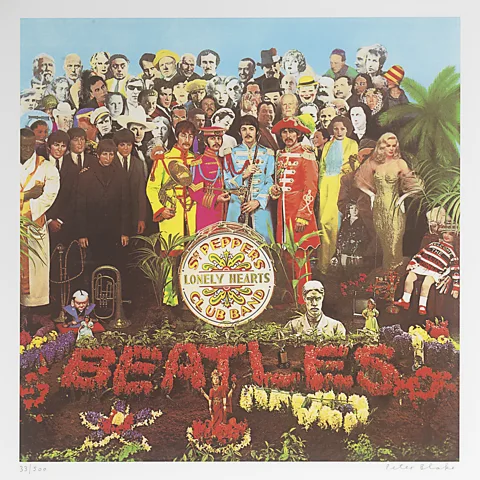

Courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot

Courtesy the artist and Waddington CustotMention Blake's name, and Sgt Pepper almost always comes next. He designed the iconic cover for The Beatles' 1967 album with his first wife, the artist Jann Haworth, and nice as it is that still, wherever he goes in the world, people brandish it for him to sign, the way that this one work has eclipsed everything else he has ever done sometimes depresses him. He has referred to it as an albatross.

Era-shaping

Born in Kent in 1932, made "pathologically nervous" by twice being evacuated during World War Two, Blake came up through Gravesend Technical College and the Gravesend School of Art, before landing a place at the Royal College of Art in London. "That never would've happened before the war," he says. "My generation, we got grants. I think that was the big change, you know, a lot of working-class boys and girls went into culture."

His cohort at the RCA included era-shaping artists such as Frank Auerbach, Bridget Riley and Leon Kossoff, plus Pop or Pop-adjacent artists Pauline Boty, Richard Smith and Joe Tilson. David Hockney, Richard Hamilton and RB Kitaj were a couple of years behind.

Blake and Smith were flatmates, "and we would go to jazz clubs. With Joe it was reggae – he was a very close friend and of course I was in love with Pauline, though she didn't feel the same way. 'I do love you, Pete,' she said to me, 'but not in that way'. So college was a time of some personal lows but some enormous highs."

Image of screenprint courtesy of Bonhams

Image of screenprint courtesy of BonhamsBlake's coup de theatre, the surprising twist he brought to the plot of British art, came of his pillaging popular culture. "I think because I'm working class, and that was the natural interest of the family, you know?"

He hit the big time in 1961, with a self-portrait in a denim suit, his top half covered in badges. Denim – essential Mod gear – had only recently become available in Britain, though Blake had been cutting his own from boiler suits for years. That plus the baseball boots, the stars and stripes patch and Elvis mag proclaimed Blake's admiration for US pop culture. Now in the Tate, it won him the John Moores painting prize, plus a spot in Ken Russell's landmark 1962 documentary, Pop Goes the Easel.

The following year, Blake met and married Howarth, who was making her own name in "soft sculpture" – stuffed calico bodies and still lifes. For a time the two worked side by side – was there any dialogue between her sculptures and his? "She'd already made the early pieces. Obviously I would've encouraged her and been aware of what she was making, but no, I don't think so."

Her father, the Oscar-winning art director Ted Howarth, had some influence, though – at least indirectly. Knowing of Blake's Americanophilia, he arranged for his son-in-law to sketch props at Universal Studios, then lent him a gold Corvette Stingray convertible to drive around California.

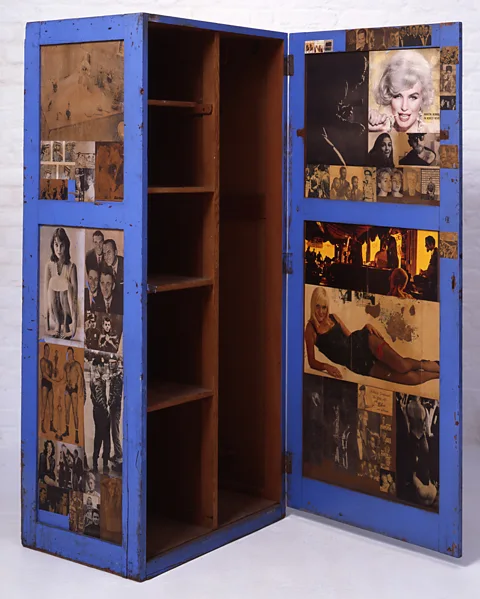

Courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot

Courtesy the artist and Waddington CustotSome of Blake's Pop experiments began there, including works that featured packaging (before Andy Warhol), flags (before Jasper Johns) and comics (before Roy Lichtenstein). "That I did those things early, before the artists who got the credit for inventing them, it's important to me," he says.

Blake and I look through photographs of his sculptures together. They range from found object constructions to bronze casts and gleaming stones that remind him of a Henry Moore. Other pieces pay homage to Constantin Brancusi, to Superman and the stunt performer Evil Knievel – "people who really achieved" – and to Snow White. That piece employs the original figurine from the Sgt Pepper shoot, though here she is decidedly less demure: attacking a bagpiper in a Swiss chalet.

For Blake, selecting the sculptures for the show has been a chance to revisit long-forgotten memories. Air Force Locker (1959), for instance, was inspired by his time in the RAF on National Service. "Your locker is your life," he says. "Everything inside it exactly where it is supposed to be, though they let you put pin-ups inside. I don't think anyone else had presented a piece of furniture as a work of art like that back then."

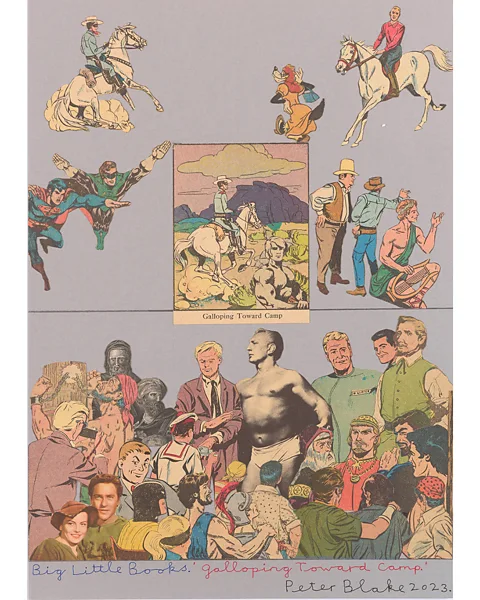

The exhibition will also present Blake's latest collages, plundered from Victorian-era encyclopaedias, Hogarth etchings and Big Little Books, a vintage US series. Making the collages this last year has required no little grit and determination: "I use a Zimmer frame now, so if I'm here, say, and my scissors are across the room, it's a drama. I don't know how much I'm physically capable of making since I've become – what shall we call it – infirm."

Courtesy the artist and Waddington Custot

Courtesy the artist and Waddington CustotMight he return to painting? "There are a couple of large ones I haven't finished in the studio. They vaguely haunt me, and I sometimes think I might get back there, but I doubt it. I was saying to Chrissy the other day that what I'd like to do, for a little while, is just draw people. Have them come and sit, and just quietly draw."

He smiles. "Let's not end on that. You know, in spite of the self pity, and the madness of some of it, I've had an amazing life. I'm glad I did it. I'm glad that I lived through the 60s. I'm glad I've had the span of the work. I'm glad I'm still working."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.