The 80s artists who predicted the future

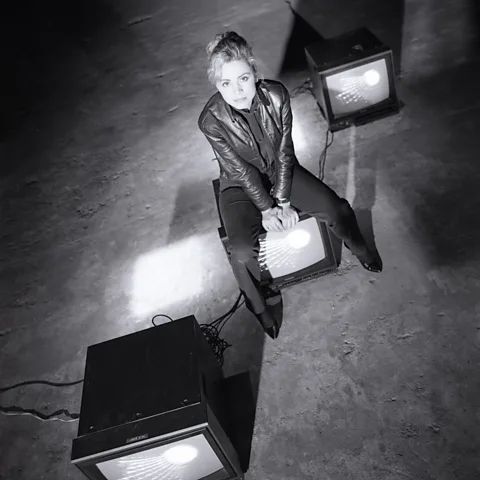

Gretchen Bender/ Sprüth Magers London/ Ben Westoby

Gretchen Bender/ Sprüth Magers London/ Ben WestobyIs the infinite imagery and information of the internet at saturation point? Emily Steer explores the art of mass-media 'incomprehension' from the 1960s to today.

The psychological impact of mass media has intrigued cultural commentators and artists since the second half of the 20th Century. Mass media can define any means of communication that reaches a large audience. Over the years this has come to include radio broadcasting, television, newspapers, filmmaking, advertising and, most recently, the internet.

More like this:

Some say that this boom of visual and aural stimuli has led to cognitive overload: the idea that we are being submerged by a vast quantity of information that our brains never could, or should, keep up with. At the most extreme end of this idea is the fear that human cognitive functioning is being unalterably impacted by this constant feed of images and information, and that this overload is numbing communication skills and impacting the way that the brain stores information. For the artists who explore this area, there is often a simultaneous fascination with the technology, and the fear of quite where it is taking the human mind.

Courtesy of Gretchen Bender Estate/ Sprüth Magers/ Photo by Hans Neleman

Courtesy of Gretchen Bender Estate/ Sprüth Magers/ Photo by Hans NelemanIn the 1980s, struck by the stream of imagery, sound and information flooding through countless television channels, US artist Gretchen Bender developed a series of immersive "electronic theatre" installations. These works combined sound, video, sculpture and performance, critiquing the pull that corporate and media content had on the collective consciousness at the time. In these works, stacks of televisions show a nauseating barrage of images jostling for attention. Animated logos, Hollywood footage and clips showing Cold War military hardware flash before the viewer, overwhelming their senses.

Now, Sprüth Magers gallery in London is presenting a solo show of Bender's work, exploring this pioneering artist as a precursor to the 21st-Century artists who create for and about the post-internet age. Born in Delaware in 1951, Bender studied art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the 1970s. She rebelled against the traditional forms of art-making that were pushed on the curriculum at that time, and instead turned to silkscreen printing. She saw this as an early means of mass communication within her practice. It was a process that enabled quick, repeated creation of almost identical works of art.

Bender was ahead of her time. Or, in the words of her ex-creative partner Robert Longo, "I think she was perfectly on time and everyone else was behind times. I met Gretchen in 1981, when I did a performance in Washington," he tells BBC Culture. "I said 'move to New York', and she did!" Longo combines filmmaking with music and art. In the 1980s he was part of the burgeoning Pictures Generation, a group of now world-renowned artists including Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger and Richard Prince, who all still explore the impact of images on our understanding of the world around us. It was a movement that Bender, with her interest in mass communication, quickly became part of.

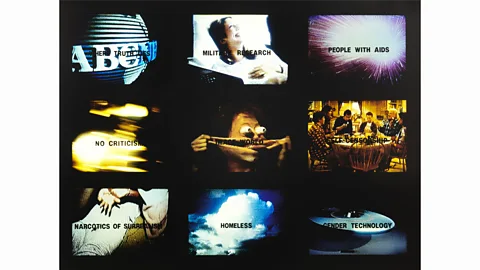

Courtesy of Gretchen Bender Estate

Courtesy of Gretchen Bender Estate"Gretchen came to live with me as the whole Pictures Generation thing was happening," Longo continues. "Cindy lived just around the corner. We'd go to parties at [artist] David Salles house. Gretchen was kind of overwhelmed by all of it and she wanted to make art. She was surrounded by all of us doing this media-orientated work. One of the big moments was when I bought a colour television set and VCR."

Bender's initial forays into technology and film editing were experimental. She worked alongside Longo on an early music video for an underground New York band. He describes their first work as "pretty awful", but they soon had requests from other, more prominent bands such as REM and New Order. The experience kickstarted Bender's fascination with editing.

"We got some home equipment and Gretchen started to do some editing," says Longo. "We were playing around at home, and I said, 'Let's just go nuts'. We started fast cutting it and putting loads of images into it. Gretchen took to it like a duck to water. At the same time, we were watching tonnes of stuff on the VCR and going to lots of movies."

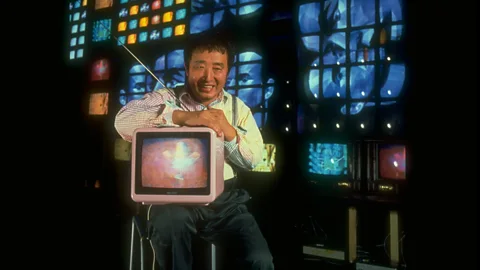

Bender's work could be seen as a natural progression from groundbreaking artists such as US-Korean artist Nam June Paik, an early adopter of video art in the 1960s. He electronically distorted sound and images and brought together footage that would not typically be associated: from commercials to news clips and political conferences. He famously coined the term "electronic superhighway" in the 1970s, predicting the virtual network of communication and information possibilities that would eventually be provided by the internet.

Courtesy of Gretchen Bender Estate

Courtesy of Gretchen Bender EstateDara Birnbaum was also experimenting with video art in the 1970s. Her feminist practice touched on the impact that television was having on US domestic life. In one of her most well-known works, Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-79), she utilised footage of the iconic superhero as played by Lynda Carter. In the work, Carter is shown in an eternal spin, as Birnbaum cuts and repeats her famous transformation from Diana Prince to Wonder Woman and back again. The work comments not just on the social role of women as secretary or superhero with "nothing in-between" but also on the hours of television being repeatedly watched at that time. In the 1970s, North American households were viewing an average of six hours per day.

'Tower of incomprehension'

Following on from this, the 1980s was a time of radical change, both technologically and politically in the United States. US President Ronald Reagan's focus on free markets and unconfined capitalism led to an increased focus on commerciality, the idea that buying and selling were the most important aspects of North American life. Bender, alongside fellow members of the Pictures Generation, responded to both of these things.

"One of the amazing changes that happened in the 1980s was the mass use of the remote control," says Longo. "It was almost like the invention of a gun. We would sit there and flick through stations endlessly. You didn't have to get up and turn the channel. In the early 1980s there was also the blossoming of video graphics, and these spinning balls and logos. Gretchen was cataloguing and recording everything on television endlessly. We made this New Order video with something like 700 edits in it. She was pushing the machines, like a mad scientist. In the 1980s Ronald Reagan also became president. He was like the first Donald Trump, and we were all really reacting against him."

In the 40 years since Bender created her electronic theatres, numerous artists have engaged in this form of work beyond those of the Pictures Generation. The sight of stacked television sets is a familiar one to regular gallery goers, and many installations still use retro technology. Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles's totemic Babel (2001) currently sits in Tate Modern's public permanent collection. A tower of hundreds of analogue radios all tuned to different stations, Babel sends a paradoxically clear message about the shortcomings of mass communication: when everyone is speaking, no one can be heard.

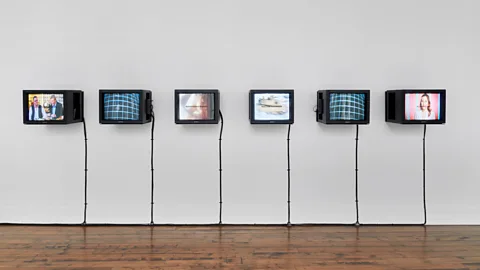

Sprüth Magers London/ Ben Westoby

Sprüth Magers London/ Ben WestobyWhen I visited Babel, the faint strains of Survivor by Destiny's Child could be picked up above the surrounding noise. Each experience of the work is different, as the radios pump through live airwaves. The installation has been referred to by Meireles as a "tower of incomprehension". The name of the work is inspired by the Biblical tale of the Tower of Babel, which was built to be tall enough to reach heaven. Aggrieved by this structure, God doomed each of the builders to speak different languages, plunging them into a divided world, and so beginning global human conflict. The work is a warning about the downside of mass media as well as a celebration of its ingenuity. Viewers can't help but marvel at the beauty and creativity of some of the devices in the stack, from 1920s valve radios to the portable electronic transmitters of more recent decades.

In the 21st Century, many artists have switched their focus from television and radio to the information overload that exists on the internet. "We started with five channels, then 20, then 100," Longo tells me. "When everyone got cable, it was like 'Woah, look at this!' It was like taking acid. We didn't have the internet, but I think it was the beginning of what's happening now."

Joey Holder is a British multimedia artist who works in collaboration with experts in other fields, from marine biologists to behavioural psychologists. The fictional environments that she creates often speak to the multitude of images and information that sit jarringly side by side on the internet. Unusual connections and endless possibilities emerge in her work.

"With the saturation of information and imagery online, it feels as if there is nothing left to be 'made'," she tells me. "I feel fatigued and exhausted by the flatness of the infinite possibilities presented to us on screen. It's as if everything is possible yet everything is the same. I address this within my work, thinking about the limits of digital information and processing, corporate capture, and how we can potentially transcend it."

Mario Ruiz/ Getty

Mario Ruiz/ GettyHolder is also concerned by the speed at which mass communication has developed, growing at an unprecedented rate that can feel difficult to keep up with. "Mass media has continued to accelerate since the time when Bender's work became prominent in the 1980s, permeating every part of our contemporary lives and creating a mass effect on the way we see, behave, think and act towards other people," she says. "I worry about this continually."

The effects of mass media and communication is an area that has been extensively studied by human behavioral experts. Dr Sharon Coen is a media psychologist and senior lecturer at Manchester's University of Salford. "I think art, paradoxically, has a better chance than I do in getting the message across," she tells BBC Culture. "If I say it, it will sound like doom. First of all, artists can take a non-traditional, non-scientific approach, which can help us to understand things in different ways. An art piece hits in the heart."

While Coen recognises the negative effects that mass media can have, she feels positive about the human ability to recognise the dangers. "There are a lot of alarmist attitudes, feelings of 'Oh my God, we're screwed'," she says. "Actually, the more I talk to people and observe my surroundings, I realise that we are very strategic. With 'doom scrolling', some people get sucked in and they spend hours and hours looking at terrible stuff online. But guess what, how did we learn about doom scrolling? Because people realised they were doing it and said 'Oh, this isn't good.' So while it is a problem, I don't think we should underestimate ourselves."

Coen traces the fear of collective cognitive decline to long before the internet was formed, and even before the visual overload of television. "A lot of my peers have a tendency to blame the internet and say it's the origin of all our problems," she says. "I keep telling them, more than 2,000 years ago Socrates hated writing. Why? Because he was saying we were going to become stupid and not be able to remember anything. He thought our cognitive functioning would change. But in writing we save mental space that we would use in trying to remember everything, and we can use that for other things. It's always a balance."

Many of today's artists have one eye on the trailblazing names who came before them, and the other on future developments that loom on the horizon. "I loathe the idea of the metaverse," says Holder, "but it seems as if this is the way that the mega-cyber corps want to take us, creating a virtual layer of reality, a simulation of life. Grandiose claims are being made about it. That it will help improve mental health, reduce crime rates and save the planet, but I'm sceptical, and think that the opposite will also be true. I think we should give up on the idea of trying to create a copy of the world in digital form, life is far too complex, it can't be simulated."

Cildo Meireles/ Tate

Cildo Meireles/ TateGretchen Bender herself had a mixed relationship with the technology and media that her work can be seen to critique. She had a fascination with the process of editing and pushing the machines she worked with to their limit. At the same time, she recognised the dangers of engaging too heavily with the media that was available to her. Longo says that he and his fellow artists were all aware of the downsides: "We were all very critical of the media. This whole thing is about speed and politics. Advanced speed is one of the most important things that has happened in recent years."

As more streaming channels are released and the internet continues to broaden its scope, this speed shows no sign of decelerating. Yet despite this increased speed and change in the precise forms of communication available since the 1980s, there is something incredibly current about Bender's work. The experience of standing in front of one of her electronic theatres, overwhelmed by a barrage of moving images, is not too distant from the feeling one might get while passing through Central London's billboards or trying to close countless pop-up adverts that block a distraction-free read of a news article. The means of communication keep changing but, arguably, the impact stays the same.

Gretchen Bender: Image World is at Sprüth Magers, London, from 3 February to 25 March.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.