The virtual vloggers taking over YouTube

A.I.Channel

A.I.ChannelFrom Japanese anime characters to Barbie, virtual YouTubers talk and act just like people — and they could change the way we all interact forever.

A young Japanese woman sporting a giant pink bow and white opera gloves looks into the camera and gleefully greets her YouTube audience. She’s about to try and solve a puzzle.

Before diving into the game, she boasts with a smile: “Well, compared to all you humans, I can clear it much faster. No doubt about it!”

Yes, this YouTube personality isn’t a real person. While she’s voiced by a human, she’s a digital, anime-style cartoon. Her name is Kizuna Ai, and she has more than two million subscribers to her channel. She’s the most-watched “virtual YouTuber” on the site.

A.I.Channel

A.I.ChannelKizuna Ai is part of an emerging trend where 3D avatars – rather than humans – are becoming celebrities on YouTube, with dedicated fanbases and corporate deals. It’s becoming so popular that one company is investing tens of millions in “virtual talent” and talent agencies are being established to manage these avatars.

It’s a movement that has big implications for the future – it could change how brands market their products and how we interact with technology. It could even let us live forever.

They act and sound just like humans

Usually, vloggers are people who speak directly into the camera to their fans, sharing things like beauty tips, product reviews and pop culture rants. But in the past year they have had to contend with “VTubers” like Kizuna Ai.

“We saw this start to take off right at the end of 2017… and it’s continued to grow,” says Kevin Allocca, head of culture and trends at YouTube. He points to Kizuna Ai’s channel as an example of the spike in VTuber popularity: it had around 200,000 subscribers last December, but well over two million just 10 months later.

Google’s Earnest Pettie says the amount of daily views of VTuber videos this year is quadruple last year’s figure. And while there’s no easy way to measure exactly how many VTubers there are, User Local, a Tokyo-based web analytics site, counts at least 2,000.

Ami Yamato

Ami YamatoThese include Nekomiya Hinata, a peach-haired character who plays combat video games, sprinkling in niceties in Japanese while gunning down foes. Another, Ami Yamato, is a British virtual vlogger based in London who has a penchant for Starbucks and strolls around in the “real” world, occasionally alongside live humans. She's been vlogging since 2011.

This isn’t yet a global trend – Allocca says VTubers are popular mostly in Japan. But in that country, the futuristic videos have got the attention of companies, keen to help these characters find popularity beyond YouTube.

A new industry?

Gree, one of Japan’s biggest mobile app developers, plans to invest 10bn yen ($88m) over the next two years into developing virtual talent, creating more live-streaming opportunities, building filming and animation studios, and giving creators resources.

“We believe that human beings need avatars beyond nicknames and profile pictures,” says Gree spokesman Kensuke Sugiyama. “Although virtual talent is currently only a niche area of entertainment, we believe that attractive 3D avatar characters and their activities in virtual worlds will take people to the next stage of the internet.”

A.I.Channel

A.I.ChannelSugiyama says that as virtual and augmented reality technologies continue to develop, more vloggers and internet users could transform into fantastical and colourful characters – which in turn could become brands themselves.

It’s not just Gree, either. Kao, a Japanese cosmetics and chemicals company, “hired” VTuber Tsukino Mito at a live event in Tokyo to appear on a washing machine’s smart screen to sell laundry detergent. The Ibaraki prefectural government created a virtual influencer last month to appear in tourism campaigns, and Kizuna Ai herself was selected by the national tourism board to appear in videos to lure foreign visitors to Japan.

This demand is driving associated industries: a talent agency in Japan launched in April that caters exclusively to virtual avatars. It’ll help clients organise events, video collaborations with other creators and more.

How did we get here?

A star is ‘born’

An early adopter of this trend is a character that’s almost 60 years old.

Barbie, the doll that has appeared across toy lines and TV programmes for decades, made her own virtual vlogging debut back in 2015, before the rise of the Japanese VTubers.

“Hi – uh, OK, let’s see, where should I start?” Barbie says as she leans back into her seat after switching on a webcam.

“My name is Barbie Roberts, I have three sisters and we live in Los Angeles – well, Malibu, but I’m originally from Wisconsin. We moved here when I was eight years old.” She sounds and looks like many other teen vloggers on YouTube. She talks about everything from personal style, to more complex topics like why girls say “sorry” so much.

Barbie YouTube Channel

Barbie YouTube ChannelCalifornia-based toy company Mattel, which owns the Barbie brand, noticed the rise in popularity of vlogging and saw an opportunity to reach kids who want to buy Barbie products.

“Barbie puts out two vlogs a month and it takes about four weeks for each new episode,” says Lisa McKnight, senior vice president and global general manager for Barbie. “A team develops each script based on topics that are relevant to a girl and authentic to Barbie the character – some vlogs tackle relevant and cultural conversations, and some vlogs play on a YouTube trend.”

Whether it’s Barbie or Kizuna Ai, many VTubers use similar technology to transform a human performer into a digital influencer.

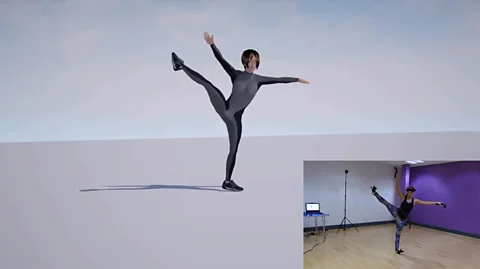

How YouTubers transform

Here’s how it often works. First, an actor stands in a studio and her head, elbows and hands are outfitted with motion trackers. As the actor moves, her motions are recorded by software that recreates full body actions from just these handful of trackers. These actions are then mapped over the shape and proportions of an animated character, which can finally be rendered on a background or live-streamed.

Meanwhile, a professional voice actor or human vlogger supplies the character’s speech.

IKinema

IKinemaThe teams behind many VTubers don’t like to give away much more about how characters like Kizuna Ai come to life. In fact, sometimes the team themselves refer to their creations as though the characters are real people.

“All we can say is that we met each other through destiny two years ago,” says Masashi Nakano, co-founder of Tokyo-based Activ8, the digital production company that brings Kizuna Ai to life.

While some content creators keep their process secret, other companies producing similar content, like Gree, are more transparent. They’re working with IKinema, a UK-based animation company that provides software to clients in a number of fields to produce animated or virtual reality content. (For example, non-VTuber actors outside and inside Japan are increasingly using this kind of motion-capture technology as part of their performances in film and video games.)

Alexandre Pechev is CEO of IKinema. He says demand out of Japan for this kind of technology has dramatically increased over the past year, and that the company now works with dozens of Japanese content creators making virtual avatars.

He says this new brand of interactive, virtual characters is new and gives YouTube entrepreneurs an opportunity to create content that couldn’t exist on platforms like TV.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow we’ll accept digital influencers

So what’s the appeal?

YouTube’s Allocca credits communities that build around them. We see these around VTubers, who often hold live chats with viewers, and fan communities on Reddit and Wikia.

“There's a unique quality to the content that virtual YouTubers offer… it isn't directly tethered to the problems of a real individual or identity,” says Reddit user David Kim, who’s a contributor to the Virtual YouTuber subreddit. “It's got the intrigue of character writing with the lackadaisical feel of live, organic, self-driven content.”

“I would say that the biggest contributor to the rise of virtual YouTube is the huge audience outside Japan who normally have interest for Japanese media and culture, such as anime,” says another fan, Kit Hakansson.

The trend within Japan of preferring digital over live-action personalities can be traced back four decades, says Izumi Tsuji, a sociology and culture professor at Chuo University. Tsuji points to a famous Japanese sociologist, Munesuke Mita, who posited that as a result of the slowed economic growth following the global oil crisis in the 1970s, many in the nation might have developed a listlessness with reality that could last to this day.

“From the latter half of the 1970s, we Japanese lost a certain goal or future of our society,” Tsuji says. “We tended to love the world of fiction. From this period, we tended to love enthusiastically anime, [video] games and idols instead of realistic movie and music stars.” One example of this, Tsuji says, is Hatsune Miku, the famous holographic pop star in Japan whose voice is digitally produced.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPechev says people choose to accept virtual YouTubers at face value. When we meet real people “what we see is their personality”, he says, not the internal workings. “We accept them as real human beings. I think the same happens at the moment with virtual YouTubers.”

Nowadays, we’re seeing more comfort in interacting with digital avatars in place of people outside Japan too.

Companies cashing in on the VTuber trend follow a similar pattern to those creating Instagram models to showcase various fashion brands. Last year, Apple announced the Animoji feature on iPhones that scans your face to create a cartoon animal avatar that uses your own facial expressions. IKinema’s Pechev says it’s a step towards accepting more complex digital characters.

“This is changing expectations. Our kids will be more comfortable to be communicating with avatars,” Pechev says. “It will be accepted in the future the same way users in Japan accept virtual YouTubers to be influential.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCould they replace human YouTubers?

But why replace human vloggers in the first place?

After all, vlogging is one of the cheapest forms of making video – switch the camera on, talk, and upload. While there might be some editing involved, it doesn’t involve costly effects or set design. So why replicate a talking head with another – more expensive – version?

It’s because the virtual character can be used at scale in ways that human characters can’t: they can appear in video games and apps outside YouTube, and as VR and AR technology improves, they can even hold virtual reality concerts. (VTuber Kaguya Luna did just that earlier this year.)

American comedian duo Rhett & Link published a vlog that’s been viewed 2.5 million times, voicing concerns that virtual YouTubers could replace humans. After all, they never get tired. Their appearances can be changed on a whim. They never demand payment or more Patreon donations.

But never fear, humans – there are cheaper, lower-quality apps YouTubers can use on their smartphones to make virtual vloggers of themselves. FaceRig, a crowdfunded facial recognition app from Romania, is a cheap way for people to turn their facial expressions into digital cartoons and animals on their smartphone, similar to Apple’s Animoji.

This autumn, Gree is releasing a live-streaming application in which users can create a VTuber of themselves on their smartphone.

“Many people have the desire to ‘want to be characters’,” says Gree’s Sugiyama, pointing to the global popularity of cosplay at fan conventions. And VTubers’ success in Japan goes deeper than fandom, Sugiyama posits. “Japanese are not good at expressing themselves openly, and I think that there are many people who really want to send out [their message] to the world, but do not want to reveal their appearance.”

Pechev wonders just how far the digitisation of ourselves could go.

If this develops in the future, he says, we could train avatars to act like us without having to re-record our movements. “It doesn’t have to do 100% of what we do, or even 80%,” he says – a character could be programmed with our voice and just enough of our actions, so that it could interact with friends and family after we die. “It could interact with other virtual avatars, or real people. Can we live forever?”

Nakano of the Kizuna Ai team says something similar: “We would like to create a world just like Ready Player One,” he says, referring to the film and novel set in a massive virtual dimension.

A.I.Channel

A.I.ChannelWhat’s next for Ai-chan, as her fans call her? Nakano mentions TV adverts, a global music festival that’s held online in VR and becoming a top idol in the virtual world.

And for now, you can keep up with your favourite VTuber throughout their day-to-day life or buy T-shirts from their merch shop.

But as Sugiyama says of the VTuber trend – that it “will allow all human beings to be released from physical constraints” – it could be a matter of time before you become one yourself.

--

Bryan Lufkin is BBC Capital’s features writer. Follow him on Twitter @bryan_lufkin.

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, please head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

{"image":{"pid":""}}