Swansea: 3D printed ear would 'transform' girl's life

BBC

BBCThe father of a 10-year-old girl set to get a new lab-built ear has said the science will transform her life.

Radiyah, from Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, has a condition known as microtia and was born without a properly formed left ear.

Now she is set to get a new ear after scientists at Swansea University began using 3D printing to build human cartilage.

Her father, Rana, said it would "help boost her confidence".

"Girls like to tie their hair up and pierce their ears and to have two matching ears will be a positive thing," he said.

The £2.5m study at Swansea University will use human cells and plant-based materials to rebuild ears and noses in a lab, which they say will eliminate scarring.

It is hoped it will be used for future treatment of people born without body parts or who have facial scarring as a result of burns, trauma or cancer.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRadiyah had been hoping to begin the process of getting a new ear fairly soon, but it had been delayed by the Covid pandemic.

Her father said she started to "lose a bit of confidence so we decided to go down the medical route".

He added: "If it wasn't for this type of technology, she would have to have a skin graft instead which would mean she'd have a big scar on her skull and also under her breast area where they would have gone to get the cartilage.

"So she would have been left with a lot of scarring but by developing the ear in a lab then she will be scar-free."

People without fully developed ears or noses have told researchers they would prefer their own tissue is used for reconstruction instead of existing plastic prostheses.

The three-year work, in partnership with the Scar Free Foundation, is attempting to overcome this challenge by 3D printing cartilage in a laboratory.

This can then be used to help form a new ear or nose.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCartilage is the main type of connective tissue in the body which provides a framework for bone structure to develop.

A patient's stem cells will be grown on to the cartilage structure in preparation for facial reconstruction.

This process will also avoid the need to take cartilage from elsewhere in the body and so reduce any further scarring.

"Successful translation of this research programme will transform the future of surgery, removing the need to transfer tissue from one part of the body to another and avoid the associated pain and scarring," said Iain Whitaker, chairman of plastic surgery at the university's medical school.

'A facial difference can be difficult'

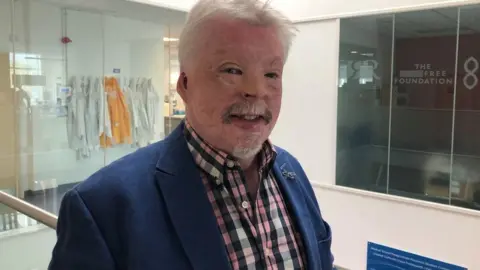

Simon Weston, who suffered severe burns to his face and body during the Falklands War, is the lead ambassador for the Scar Free Foundation.

He underwent a series of skin grafts but, at the time, there was not the research or capability to be able to rebuild his ears and nose.

"Since the age of 20 I have had to live with my scars," he said.

"In the early days this abrupt change in the course of my life caused severe psychological challenges.

"I am passionate about the issue of scarring and want people with these kind of visual differences to be accepted in society."

He said: "Having a facial difference can be difficult.

"Often we are stared at - staring is invading someone's privacy. People with scarring are real people who just want to be treated as equals."

Foundation chief executive Brendan Eley said he was "delighted" to work with Health and Care Research Wales to launch the "ground-breaking" programme at Swansea University.

"Giving surgeons the ability in the future to reconstruct people's faces using their own cells without the need for further scarring is revolutionary," he said.

"This life-changing research is part of our commitment to achieve scar-free healing within a generation for the millions of people living with scarring in the UK and across the world."