Ending the taboo of soldiers with 'broken faces'

Goldsmiths

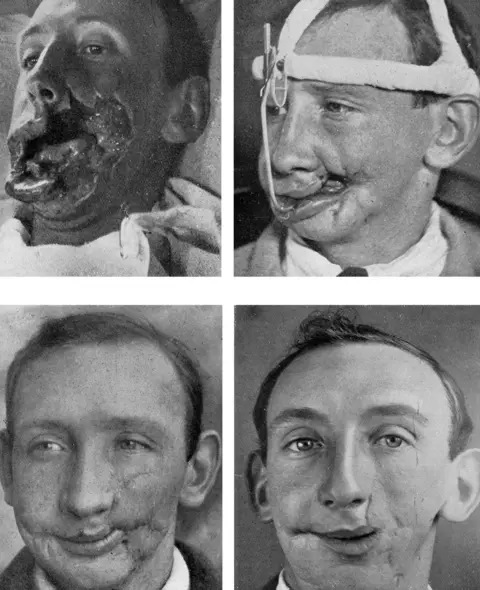

GoldsmithsWarning: This story contains a graphic image.

A World War One memorial to soldiers whose story has been described as an unresolved "taboo" is set to be unveiled.

Historian Ellie Grigsby has designed a statue commemorating the thousands of soldiers who suffered terrible facial disfigurements and who often found themselves shunned rather than welcomed back as heroes.

The statue is to be unveiled at a private event by descendants of some of the soldiers, at Queen Mary's Hospital in Sidcup, Kent, where many of the men were treated.

Ms Grigsby has researched the soldiers with "broken faces", whose uncomfortable memory she says has been neglected in war commemorations.

Mirrors banned

Her postgraduate research at Goldsmiths, University of London, found that many soldiers who returned, with their faces changed by shell and shrapnel injuries, faced social rejection and isolation.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I came across stories of mirrors being banned from hospital wards, children cowering from their fathers who came home from the front with a new face, and sweethearts who couldn't bear to look at their lovers," she says.

With today's awareness of mental health problems, Ms Grigsby says their post-war experiences must have been deeply traumatic.

The homecoming for these disfigured young men could involve a complete loss of status, broken relationships and being turned away from jobs.

She researched one soldier who was rejected by his wife - "she couldn't bear to look at him" - and was not allowed to serve customers in his old job as a tailor. But in a twist in the tale, he ended up marrying his wife's sister.

It wasn't only about appearances. Some soldiers who had injuries to their jaws and mouths struggled to eat for the rest of their lives.

Buried in a mask

In some cases, where parts of the face were missing or irretrievably mutilated, men wore metal masks.

These tin masks were painted and had artificial moustaches and eyebrows to reflect how the soldier once looked, based on photos from before the war.

Ms Grigsby says some disfigured soldiers wore these masks all the time, at home as well as in public, never showing their injuries.

"They never showed their family, some children wondered their whole lives what the face looked like, because they never saw it," she says.

Some were even buried still wearing a mask. "They lost not just their faces but their identities," says Ms Grigsby.

They had literally become the unacceptable face of war.

Pioneer surgery

The efforts by doctors to help these soldiers, carrying out thousands of operations, drove advances in reconstructive surgery.

These medical pioneers, who used their experiences at the hospital in Sidcup, have been widely recognised.

But Ms Grigsby says the injured soldiers themselves have had much less attention - with an awkwardness and public discomfort about their fate.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The monument to be unveiled will include words from Ward Muir, an orderly working at the hospital who wrote about working with men whose "hideous" appearances could be so unnerving.

"He finds that he must fraternise with his fellow men at whom he cannot look without the grievous risk of betraying by his expression, how awful is their appearance," he wrote.

"Hideous is the only word for those smashed faces. To talk to a lad who six months ago, was probably a wholesome and pleasing specimen of youth, and is now a gargoyle, and a broken one at that, is something of an ordeal."

'Airbrushed' out of memorials

Ms Grigsby has become a campaigner for their cause - raising the funds for the monument, with her design including a real World War One helmet.

But why would someone in their 20s be so engaged by this?

She says the shunning of people over their appearance has a particular resonance for today's young people who are under constant pressure over how they look.

Goldsmiths

Goldsmiths"Social media has a huge influence on how people identify as individuals," she says.

In a culture of selfies and "narcissism", the idea of being blamed for looking unusual or unattractive still has a contemporary relevance, she says.

There is also a sense of righting an injustice. Ms Grigsby says there are many memorials to World War One, with often elegant depictions of heroic soldiers.

But she says there has been an "airbrushing" of the stories of men whose personal struggles continued for decades after the war.

"Memory is a choice," she says.