Newcastle University project captures Lockerbie memories

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn December 1988, terrorists blew up a passenger jet over the Scottish town of Lockerbie, killing 270 people in the air and on the ground. Historians have been recording the experiences of those who responded to the atrocity. They shared some of their stories with the BBC.

On 21 December 1988, Brian Wright was working as an air traffic controller at Teesside Airport.

He didn't know it, but he was about to become one of the first people to realise the Lockerbie bombing had taken place.

"I was on duty with two of the colleagues down in radar and we were waiting for the Aberdeen flight," he said.

He was monitoring radar when, a few minutes after 19:00 GMT, he saw what looked like an arc of chaff - little foil strips released by military aircraft to confuse radar - stretching from the west side of England across to the North Sea.

It was the aftermath of the explosion on board Pan Am Flight 103, heading from Heathrow to New York, with the "chaff" formed by particles from items such as credit cards and passports as they fell through the atmosphere.

In the 35 years since, many of the stories of those on the plane and in the Scottish town have become well known.

Now others like Mr Wright, who came from further afield and found themselves caught up in the aftermath and ensuing investigation, have shared their stories with a research project undertaken by Newcastle University.

Brian Wright

Brian WrightHistorian Dr Andy Clark has worked alongside Dr Colin Atkinson, a criminologist based at the University of West Scotland, to gather oral history recordings of subjects including police officers and mountain rescue specialists over the last five years.

In that time, they've amassed a total of 26 hours of recordings and built up a detailed picture of the memories of the people investigating what happened at the time.

The material collected as part of this project is currently being stored at Newcastle University and Dr Clark hopes it will be made available to the public in the next six to nine months.

Although he wasn't born when it happened, Dr Clark, who comes from Greenock, Inverclyde, has long had an interest in the story of the Lockerbie bombing.

He lived "literally next door to the prison" where Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the only man convicted over the Libyan-linked bombing, was held.

Dr Clark said he had vivid memories of the media circus that descended on Greenock when al-Megrahi was released in 2009 - eight years into a life sentence - on compassionate grounds after being diagnosed with terminal cancer.

"Every time it was reported after that, you could always see my mum and dad's house," Dr Clark said, adding: "It was a connection to the story for me.

"When I met Colin Atkinson in 2017, we realised no one in Britain had done an oral history on [Lockerbie]."

One of the people they spoke to was Carl Hamilton, who was part of the Northumberland National Park Mountain Rescue Team in 1988.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the evening of the 21 December, he was winding down for Christmas with his caving club at a pub in Newcastle.

"It came on the TV in the corner of the pub that there had been an air crash over Lockerbie," Mr Hamilton said, adding: "I didn't think we would be involved at that point because Lockerbie is, you know, it's in Scotland and it's further north.

"But we were called out the following morning."

The mountain rescue team was called upon to find debris from the explosion, with artefacts found as far east as Alnmouth in Northumberland some 70 miles (113km) from Lockerbie.

"The thing most evident initially on the first day on the open hillside near Kielder Forest was insulation material," Mr Hamilton said, adding: "Everything that we picked up we put into evidence bags.

"Anything of greater significance we noted the grid reference where it was found. At the end of the day you came in with your evidence bag and signed it over to the police."

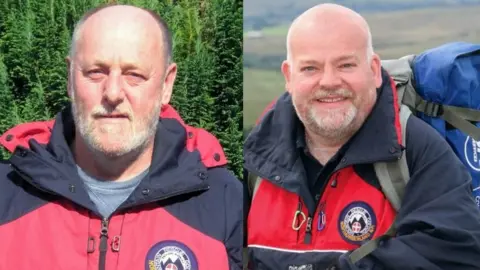

Northumberland MRT

Northumberland MRTMr Hamilton's mountain rescue colleague Pete Roberts recalled the emotional toll of the work they found themselves doing.

"The main thing was the fact it was near Christmas and people were going home," Mr Roberts said, adding: "It did hit home and particularly once we started finding personal effects.

"We [were] finding Christmas presents and things like that, and that really brought a human element, it wasn't just looking for bits of a plane.

"This once belonged to somebody, you know?"

All finds were plotted on a map with a pattern of two distinct lines of debris emerging.

"We could predict over a period of time where to go and look next," Mr Roberts said, adding: "We went all the way across to the coast over a period of three weeks."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe said a helicopter pilot who flew over Kielder likened the view to someone having "dumped a giant skip over the top of the trees".

The academics recently shared their findings at a gathering at the University of Syracuse in New York, where 35 of the ill-fated passengers were students.

"From speaking to the families, there was a real sense of gratitude to the police officers and the people of Lockerbie for the dignity and respect that they showed," Dr Clark said.

He said even now, many of the now-retired officers from Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary only spoke to him on condition that their memories would only be kept as part of this project.

"We were interested from an academic position," Dr Clark said, adding: "We wanted to speak to people who hadn't so far been part of the narrative.

"The main thing that came across was that everyone involved was determined to do a good job.

"There was a strong sense that there were families across the world relying on the police in Scotland and those volunteers in Northumberland to find out what exactly had happened and to recover the personal effects of their loved ones.

"Even all these years later, that still came across in the conversations we had."

Follow BBC North East on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].