Lockerbie: An atrocity that caused heartbreak around the world

EPA

EPAIt's a simple thing, reading out a list of names, but its impact in a courtroom 22 years ago was devastating and unforgettable. Soon it could happen again.

There were 270 of them. The youngest victims were just babies. The vast majority, 190, were American; 43 were British. The rest came from 19 other countries. This atrocity caused heartbreak around the world.

The list was read out in a converted US military base at Camp Zeist in the Netherlands, where through a deal negotiated in part by Nelson Mandela, a specially convened Scottish court was hearing the case against two Libyans accused of the Lockerbie bombing.

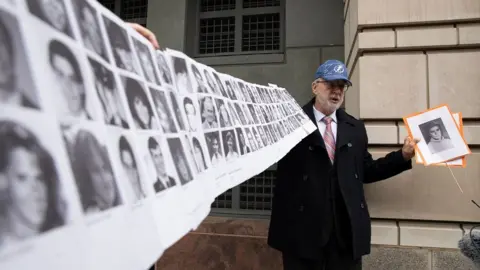

It took the Scottish prosecutor, Alastair Campbell, almost an hour to get through the names of the people who died on Pan Am 103 and on the ground in Lockerbie when their homes were obliterated by falling wreckage, four days before Christmas in 1988. He did so accompanied by near silence.

It was the start of a nine month trial and in January 2001, the verdicts were announced. Standing in the queue to get into the courtroom, I realised I was surrounded by relatives of people who died. I was there for work, to witness a huge international story. They were there for justice, for answers, perhaps even for closure, if that's ever possible in such a case. I'm not going to try to guess how they felt.

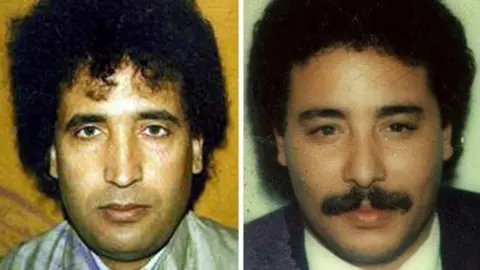

The three Scottish judges had found Abdelbaset Al Megrahi guilty, his co-accused Al Amin Khalifa Fhimah, not guilty. Only one man has ever been convicted of the mass murder when others must have been involved. Outside, American relatives welcomed the verdict but expressed their anger that the dictator they regarded as the mastermind of the murders was not in the dock. Colonel Gaddafi and his regime survived for another decade.

PA

PASome British relatives, notably Dr Jim Swire, who had fainted when the verdicts were announced, soon declared that Megrahi had been the victim of a miscarriage of justice. To this day, Megrahi's supporters believe passionately in his innocence but in the months and years that followed, Scottish judges rejected two appeals made in his name and his conviction stands. Libya's involvement in the bombing has never been disproved.

The circumstantial case put together by Scottish police and prosecutors and their American counterparts was that the bombing was carried out by the Libyan intelligence service. The indictment which listed the charges against Megrahi and Fhimah mentioned the name of another Libyan agent, Mohammed Abuagela Masud.

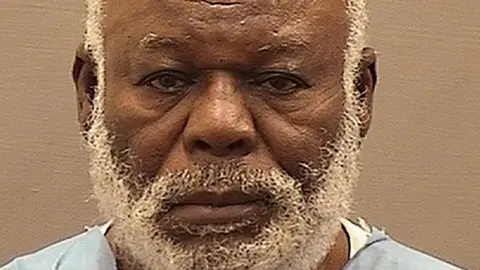

More than 21 years after the verdict at Camp Zeist, Masud has appeared in the US District Court of the District of Columbia, accused of making the bomb that blew apart Pan Am 103. For the first time in over two decades, just nine days before the 34th anniversary of the bombing, a new suspect was facing charges over Lockerbie.

Reuters

ReutersIt is the culmination of decades of work by investigators in Scotland, the rest of the UK and the US but there must be a long way to go before a second Lockerbie trial brings back its verdicts.

Masud's alleged confession was made in custody in Libya the day after the US ambassador was killed in Benghazi on 11 September 2012.

In Libya, Masud's family have told the media that he's a sick old man. There's widespread anger that he was somehow spirited out of the country and into American custody.

The Lockerbie bombing has always been controversial, with competing theories about why it happened and who was responsible. A second Lockerbie trial will examine evidence that's old and new. It should cast new light on the events of 1988.

At the court in Washington, with Masud listening, an US government prosecutor said: "Although nearly 34 years have now passed since this defendant's attack, countless families have never fully recovered from his actions and will never full recover."

More than 3,000 miles from Lockerbie, another chapter has opened in this heartbreaking saga. Someone else will doubtless stand up in a courtroom and read out 270 names.