Why was 'failed' teenager Jacob not in school for two years?

Familyhandout

FamilyhandoutJacob was found dead in his bedroom in April 2019. The 16-year-old boy had been groomed and plunged into a world of drug trafficking by so-called "county lines" gangs.

Major failures by the authorities in Oxfordshire have recently been exposed, including one glaring fact, he had not been enrolled in a school or provided any type of education for 21 months during which time he fell into a life of crime.

This absence played a "significant role" in leaving him "highly vulnerable" to being criminally exploited, a damning serious case review concluded.

But why was Jacob allowed to fall through the cracks?

Oxfordshire County Council admitted "more should have been done" but has so far refused to answer further questions on the matter.

The Conservative-run council's leader Ian Hudspeth and cabinet members for children's services and education - councillors Steve Harrod and Lorraine Lindsay-Gale - have also declined to comment.

FamilyHandout

FamilyHandoutJacob was a "cheeky, determined and friendly child" who experienced numerous "adverse childhood experiences", the report said.

He moved from his home in Oxfordshire with his mother to the North East of England during his primary school years.

He was excluded from school in Year 6 due to his behaviour, described in the report by mental health professionals as "defiant and oppositional", before he and his mum returned to Banbury in July 2017.

But instead of living a typical teenage boy's life and preparing for exams, Jacob was "duped" into dealing drugs and carrying out assaults away from the classroom.

So why was he not provided with an education?

Investigators found there was "a lack of responsibility and accountability" in the council's education department which led to Jacob's case being "passed from pillar to post".

The report detailed the complex relationship between local authorities and academy schools, which hold the power for the pupils they want to enrol.

However, in cases such as Jacob's, councils can escalate matters to the Department for Education or secretary of state, to ensure schooling is provided.

Yet in Jacob's case, a referral was not made "as it should have been".

There "appeared to be a cultural view" that framed escalating cases to government level as "a slow and cumbersome process with no guarantee of a positive outcome", the review said.

It meant Jacob remained in "limbo" after being rejected from four educational settings due to his "perceived behaviours and risks to other students", which had derived from his previous exclusion.

Being constantly rejected from schools left Jacob "frustrated that he had nothing to do in the day and [he] wanted to be in school", the report said.

"Jacob talked to his friend of his idea of buying a school uniform and walking into a school 'to just feel like others' of his age," it added.

It was during this time that he began to be criminally exploited.

He was reported missing more than 20 times during the time he lived at home and the five months he was in the care of the council. He owned at least three mobiles phones and was seen selling drugs.

He was recorded as a suspect or an offender in 26 police reports, mostly for violent crimes which included assaults against his mother. However, Jacob was never brought before the courts or convicted "due to a lack of evidence and victims not wishing to press charges".

"Reachable moments" were missed to help him when he was treated for knife injuries to his hand and face, it was noted.

The police did make efforts to engage with Jacob through a reformed gang member, but the approach did not work.

The impact of those lost opportunities led to him seeing himself as "untouchable" to the police and court system and he remained an easy target for exploiters who knew he was "clean skin" and not being monitored.

'Crying for help'

From October 2018 it was suspected he was accruing mounting drug debts, was using drugs and alcohol, and was "tearful, bored and low in mood" towards the start of 2019.

Following his death, a coroner concluded he was "intoxicated and distressed" when he died but said there was "insufficient evidence" that he intended to kill himself.

Jacob's grandfather used a new car analogy to describe how he believed the authorities responded to his grandson.

"You buy a new car, you get to know it and you look after it to begin with," he told the review.

"After a while it loses its shine and appeal and you do not have the same level of interest in it. This is what happened to Jacob, when the system did not know what else to do, the focus was lost on helping him."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFollowing the review, the county council said in a statement steps had since been taken, including introducing a "rigorous and robust system" to ensure that if a child is not awarded a school place within 15 school days of an application then "their requirements will be escalated".

The local authority said the case provided "important learning, but it is not characteristic of the wider situation in terms of how child drug exploitation is handled".

Professor John Howson, a current Liberal Democrat county councillor and education expert, told the BBC Jacob's case was one of a "boy who was crying for help".

"The really big failing was that nobody wanted to take responsibility for this child. No-one said this child was my responsibility," he added.

The government did not comment when asked if more power should be given to local authorities over school admissions or if cases in the current referral process were often delayed.

It said academies are their own admissions authority and "must meet all the mandatory provisions of the School Admissions Code".

Other children not in school

A government spokesperson said it was making "significant investments" to improve care services for vulnerable children and had launched an "independent wholescale review" of children's social care to reform the system.

At the same time Jacob was out of school, he was not the only child in Oxfordshire not receiving an education.

Investigations from the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman found for 14 months between March 2017 and May 2018, a teenage girl in the county went without a formal education.

In another case, the council failed to ensure a child received suitable alternative education for a year on-and-off between March 2017 and April 2018.

In June 2017, a month before Jacob returned to live in Oxfordshire, councillor Mr Howson, asked a question to the council's cabinet about the length of time it was taking for children, who had been placed in care and relocated outside of the county, to be enrolled in a school

The response was that it was "exceptional" for a child to be taken on by a school in under two weeks and the picture was "even worse" for secondary pupils.

Iryna Pona, policy manager at The Children's Society, told the BBC any child can be at risk of exploitation, but added children who are partly or permanently excluded from school are in "greater danger" of being targeted by criminal gangs.

"Sadly, at the moment too many young people are falling through the cracks. For those children it is imperative they are seen as victims, who have been groomed and coerced into criminality," she added.

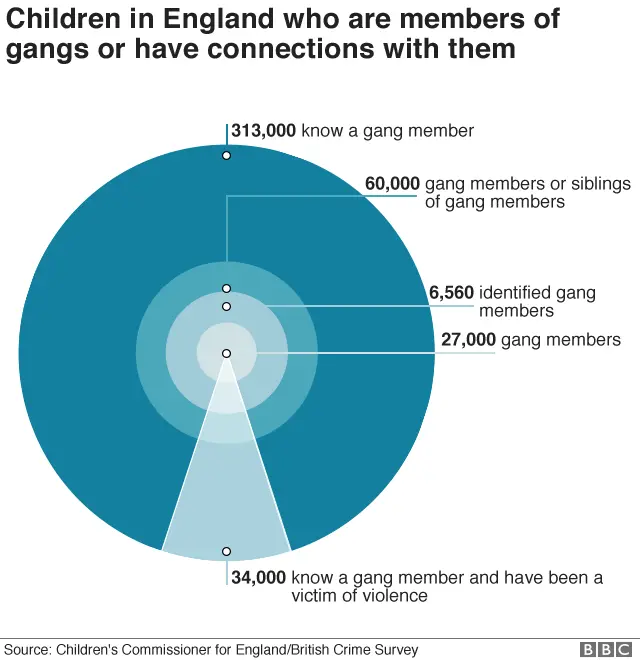

Children's Commissioner Anne Longfield said Jacob was one of a "growing number" of children - 27,000 according to her research - who are vulnerable to exploitation from gangs.

"No child should die because parts of the system didn't think that child was their problem," she said.

Thames Valley Police said it recognised it did not get the "balance right" in Jacob's case between "dealing with children who are exploited but may also pose a risk to and offend against others".

The serious case review called for a national strategy as "local partnerships are likely to continue to struggle to develop properly resourced and effective solutions" to this type of crime.

Ms Longfield said an approach similar to that taken to combat child sexual exploitation was needed to "recognise that these children are victims of ruthless criminal gangs and get them early help and support - not criminalise them".