How do we know how many children are in gangs?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGang activity often takes place under the radar of the authorities, and even defining what counts as a gang is not straightforward.

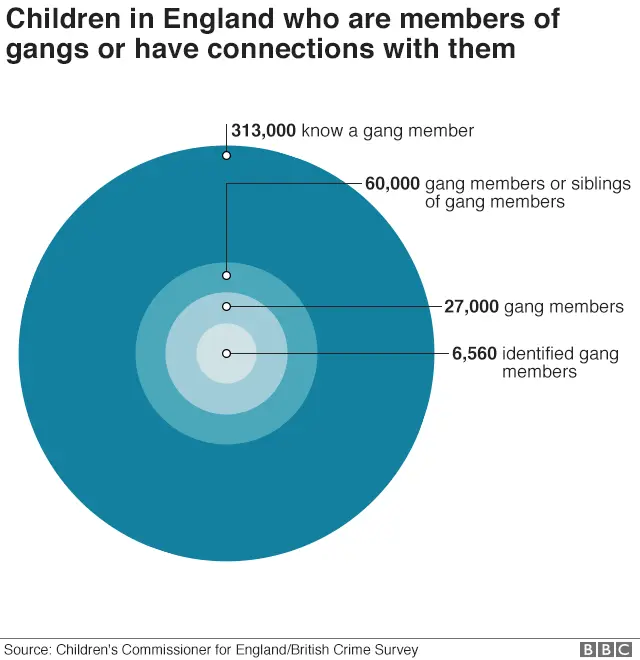

A report has estimated there are 27,000 children in gangs, as the Children's Commissioner for England Anne Longfield calls on professionals to "learn from the mistakes of child sexual exploitation" and treat children as victims not perpetrators.

So how did they reach this figure?

Each year, the Office for National Statistics runs a crime survey asking a representative sample of households about their experience of crime. For the past three years, it has asked children aged 10 to 15 whether they considered themselves to be a member of a street gang.

The Office of the Children's Commissioner in England did its own calculation using these figures.

Last year, of a sample of about 4,000 children, 0.7% (about 30 children) said they considered themselves to be in a street gang.

This figure was scaled up to give the estimated 27,000 figure for the whole population of England for a single year.

That's an estimate, but the report gives another much lower figure of 6,560 children actually known by youth offending teams or children's services to be involved in gangs.

Ms Longfield's report concludes that the difference between the higher and lower figure is down to the fact that most gang members are not known to authorities.

We do not know that for sure though - it is certainly likely that there is a group of young people involved with gangs who are not known to the authorities, but we cannot be sure as many as 27,000 children are in gangs.

Since these figures come from a bespoke analysis, comparable individual figures for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are not available.

PA

PAWhen it comes to gang violence and criminal activity, there is no national data.

But in London, the Metropolitan Police holds a database known as the Gangs Matrix, containing names of between 3-4,000 "persons of interest" at any one time.

The database has been criticised for disproportionately targeting young black men who might not have links to violent crime.

Last year the Met said that all its officers were "highly-trained and experienced in working with, and recognising the signs of, gang affiliation and gang membership".

"By identifying high-harm gang members and targeting them through intelligence-led enforcement, the number of violent offences committed by gang members has been reduced," a Met spokesperson said.

The Met also "tags" violent crimes as gang-related if it believes it has enough intelligence to do so.

In 2017, the last time it published estimates, one in every 500 violent crimes recorded by the Met Police was tagged as gang-related. Since 2010, 15% of homicides in the capital have been linked to gangs.

Knife crime

While information of gang membership is difficult to capture, we do know that knife carrying among children is increasing.

Almost 21% of 21,380 knife possession offences last year were committed by 10 to 17-year-olds.

Since 2014, the number of knife possession offences committed by 10 to 17-year-olds has increased by 70%.

Hospital admissions for assault with a sharp object for 18-year-olds and under have also increased by 70% since the year to March 2014, reaching 813 last year.

This data shows the problem is increasing, but it does not tell how many children are carrying knives in total.

Last year, 0.6% of 10 to 15-year-olds said they had personally carried a knife and and 5.7% knew someone who had, according to the ONS's crime survey.

This does not tell us whether they are carrying weapons for gang-related reasons, though.

In schools

Knife carrying also appears to be increasing in schools.

Data from 21 police forces in England and Wales obtained through a Freedom of Information request showed 363 sharp instruments were found on school property in 2017-18.

This is an increase from 94 in 2013-14.

The report said children who say they are involved in street gangs were more likely to have been excluded from school.

Research by centre-left think tank the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) also suggests that children who have been excluded from school are more likely to enter the criminal justice system.

The Children's Commissioner's report points out there are multiple risk factors associated with children becoming involved with gangs.

The report says that children in gangs who are known to children's services are more likely than others in the system (already a vulnerable group) to have mental health problems, special educational needs and to come from homes where there is domestic violence or substance misuse.

Children who have been in gangs and are now in the criminal justice system are 76% more likely than other young offenders to have not been having their basic care needs met at home, according to professional assessments.

Drugs

The rise of County Lines has also increased concerns of children being pulled into, and exploited by, drug gangs.

County Lines involve city-based drug gangs expanding their drug dealing into smaller towns and rural areas, with violence often being involved to protect the routes.

The National Crime Agency estimates that the number of dedicated phone lines dedicated to taking orders from users increased from about 720 to 2,000 between 2017 and 2018.

Individuals, often vulnerable people susceptible to exploitation, will then take the drugs from the base to consumers.

Two-thirds of police forces link County Lines to child exploitation by gangs.

Given the illicit nature of the operations, total involvement is difficult to capture but the majority of referrals received by the National Crime Agency concern 15 to 17-year-olds.