Endurance: 'Finest wooden shipwreck I've ever seen'

Endurance, the lost ship of Anglo-Irish explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, has finally been identified on the floor of Antarctica's Weddell Sea. The vessel was crushed by sea-ice and sank on 21 November 1915, forcing Shackleton and his men to make a heroic escape on foot and in small boats.

Marine archaeologist Mensun Bound described the condition of Endurance to the BBC.

"Without any exaggeration this is the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen - by far.

It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation.

You can even see the ship's name - E N D U R A N C E - arced across its stern directly below the taffrail (a hand rail near the stern). And beneath, as bold as brass, is Polaris, the five-pointed star, after which the ship was originally named.

I tell you, you would have to be made of stone not to feel a bit squishy at the sight of that star and the name above.

And just under the tuck of the stern, laying in the silt is the source of all their troubles, the rudder itself. You will remember that it was when the rudder was torn to one side by the ice that the water came pouring in and it was game-over. It just sends shivers up your spine.

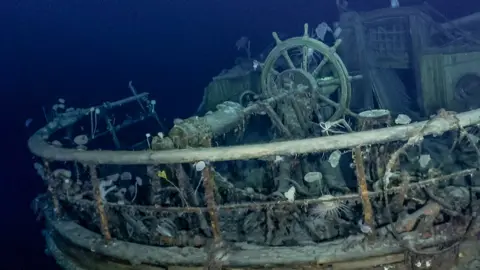

When you rise up over the stern, there is another surprise. There, in the well deck, is the ship's wheel with all its spokes showing, absolutely intact. And before it is the companionway (with the two leaves of its door wide open) leading down to the cabin deck. The famous Frank Hurley (expedition photographer) picture of Thomas Ord Lees (motor expert) about to go down into the ship was taken right there.

And beside the companion way, you can see a porthole that is Shackleton's cabin. At that moment, you really do feel the breath of the great man upon the back of your neck.

FMHT/National Geographic

FMHT/National GeographicThe funnel is still there, but not upright, lying semi-thwartships (almost at a right-angle to the keel), still with its steam whistle attached. Beside it is the engine room skylight. We could look down through it. I was hoping to see the cylinder heads of its triple-steam expansion engines, but couldn't quite make them out.

Near midships there is a boot, with another one, maybe its pair, in the debris field beside the wreck; also several plates and a cup.

When the mast fell, it crushed the ward room with the bridge deck above, but you can see the outline of the wardroom and beside it the galley and pantry. One wall of the galley is still standing with its two forward portholes intact.

FMHT/National Geographic

FMHT/National GeographicOn the weather deck, you can see the forward hold and skylight with the fo'c'sle deck (the upper-deck forward of the foremast) just beyond.

The fo'c'sle deck is damaged, for although the vessel went down keel first, she was down slightly at the bow so it was that part of the hull that first struck the seabed and so took the shock of impact.

The capstan is still visible on the fo'c'sle deck and beside it is one of the anchors. The other anchor broke free; it snakes out over the seabed.

The bow looks amazing. You can see its forward raking stem and the metal-shod cutwater that cleaved the ice.

FMHT/National Geographic

FMHT/National GeographicThe masts, spars, booms and gaffs are all down, just as in the final pictures of her taken by Frank Hurley. You can see the breaks in the masts just as in the photos. There is a tangle of ropes, blocks and deadeyes.

You can even see the holes that Shackleton's men cut in the decks to get through to the 'tween decks to salvage supplies, etc, using boat hooks. In particular, there was the hole they cut through the deck in order to get into "The Billabong", the cabin in "The Ritz" that had been used by Hurley, Leonard Hussey (meteorologist), James McIlroy (surgeon) and Alexander Macklin (surgeon), but which was used to store food supplies at the time the ship went down.

I had been hoping to find Orde Lees' bicycle, but that wasn't visible, nor were there any of the honey jars that Robert Clark (biologist) used to preserve his samples that I also hoped I might find.

The depth is 3,008m (9,868ft).

Endurance was found just over four nautical miles (7.5km) and roughly southward of Frank Worsley's famous sinking position (68°39'30" South; 52°26'30" West).

We found the wreck a hundred years to the day after Shackleton's funeral (5 March 1922). I don't usually go with this sort of stuff at all, but this one I found a bit spooky."

RGS-IBG

RGS-IBG

All wreck imagery is courtesy of the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and National Geographic