Shackleton's Endurance: Modern star maps hint at famous wreck's location

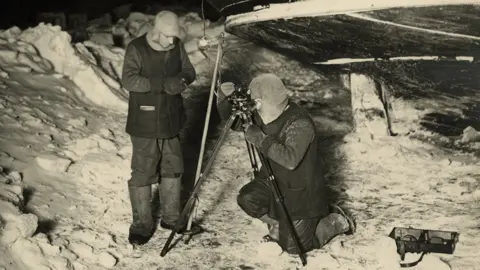

University of Cambridge/SPRI

University of Cambridge/SPRIFor many, the lost ship of Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton is the greatest of all undiscovered wrecks.

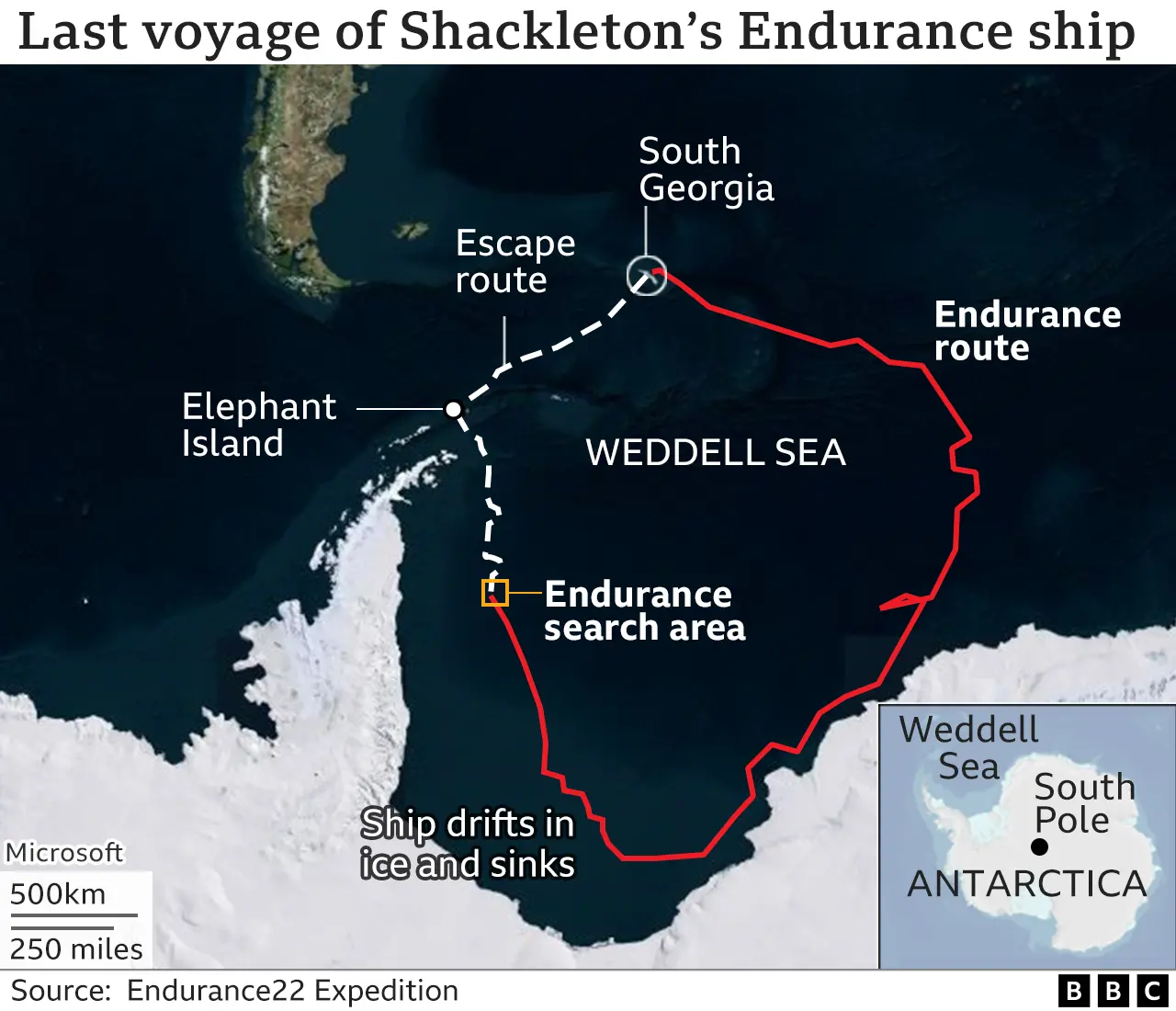

In part that's because of the extraordinary story that surrounds the 1915 sinking of the Endurance - an epic tale of 28 men who somehow survived and escaped the calamity of becoming stranded in the frozen wastes of the Weddell Sea.

But the allure also has something to do with the daunting challenge the wreck now presents to anyone who might consider trying to find it.

What remains of the Endurance is 3,000m down in waters that are pretty much permanently covered in thick sea-ice, the same sea-ice that trapped and then ruptured the hull of Shackleton's polar yacht.

You need a good strategy, immense skill and an enormous dollop of good luck just to get near the sinking location. A team of hopefuls is on its way to the Antarctic right now.

Getty Images/SPRI

Getty Images/SPRIThere's an assumption we know well where the ship lies on the ocean bottom because Shackleton had a brilliant navigator on his ill-fated voyage, a man called Frank Worsley. Using a sextant and chronometer, he calculated the coordinates for the position where the punctured Endurance slipped below the floes on 21 November, 1915.

It's in his log book. 68°39'30" South; 52°26'30" West.

But how accurate is this? Three modern-day researchers - Lars Bergman, David Mearns and Robin Stuart - have long pondered this question.

They've tried to sum the various errors that may have crept into Worsley's measurements and have concluded in a new pre-print paper that the true sinking position may be several kilometres to the east of where the navigator computed it to be.

"There's a lot of things to consider; you cannot just take Worsley's position for granted and go right to that location. You've got to use your judgement," said David Mearns who's found many historic wrecks in his career.

Mearns and his two colleagues have submitted their paper to the Journal of Navigation but have taken the decision to publicly release it now because it could be useful to the search that is about to get under way.

The paper's central concern is the performance of the marine chronometers, or clocks, used by Worsley to get a longitude fix.

Previous work by Bergman and Stuart had suggested these were running much slower than the crew of the Endurance had realised or accounted for - an error that would put the sinking west of Worsley's recorded position. But Mearns has now picked up a really quite critical error in the clocks' calibration that pulls the location back and off to the east.

The investigation highlights the story of Reginald "Jimmy" James, the ship's physicist on Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

It was James who showed Worsley how he could work out the drift in the time-keeping of the chronometers from lunar occultations.

There's a picture of the two men at the stern of the Endurance observing stars as they disappeared behind the Moon. The timing of these movements had been predicted and published in a nautical almanac. Its tables kept the chronometers honest. And it's fair to say that without the occultation observations, Shackleton's crew would have misjudged their location by many, many kilometres.

But here's the fascinating part in this story. Modern maps of the sky are remarkably precise, far more so than the catalogues used to compile the almanac employed by James and Worsley. Had the men been in possession of today's information, they'd have realised their clocks were actually running 22 seconds faster than they were accounting for. Just this error would have put the Endurance more than 3km east of Worsley's log coordinates.

Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

SPRI/Uni of Cambridge

SPRI/Uni of Cambridge- December 1914: Endurance departs South Georgia

- February 1915: Ship is thoroughly ice-locked

- October 1915: Vessel's timbers start breaking

- November 1915: Endurance disappears under the ice

- April 1916: Escaping crew reaches Elephant Island

- May 1916: Shackleton goes to South Georgia for help

- August 1916: A relief ship arrives at Elephant Island

However, this is but one uncertainty that needs to be considered when examining the reliability of those coordinates. Not often recognised is that Worsley didn't get a fix on the expedition's position until fully 19 hours after the Endurance had gone down. On the day of the sinking, a view of the Sun, needed to make a navigational observation, was impossible because of thick cloud. And neither was it possible in the two days before the sinking. Worsley's coordinates rely on an estimate of the direction and speed of the shifting sea-ice during those three "missing" days.

Bergman, Mearns and Stuart are convinced, though, having looked at all the issues, that the real longitude is off to the east. Their latest paper, they say is "a more complete, accurate and reliable basis for determining the most probable sinking location of Endurance". It's been shared with the Endurance22 project which is currently headed into the Weddell Sea to look for the wreck with underwater robots.

The project's exploration director, the marine archaeologist Mensun Bound, said the paper had been read with interest, although he did not disclose whether its analysis would influence his team's thinking. Everyone must have their own assessment.

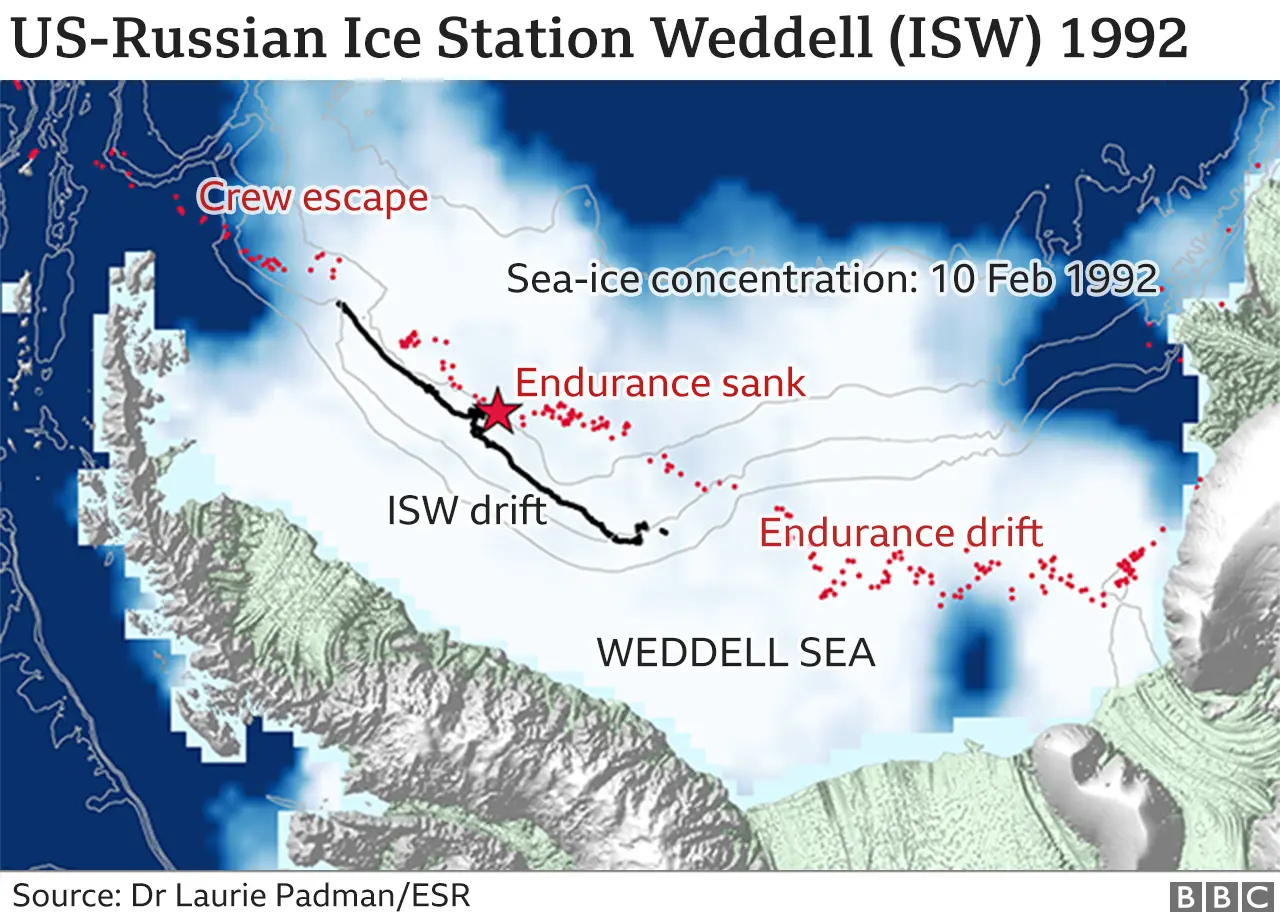

Interestingly, this past week has marked the 30th anniversary of the start of Ice Station Weddell (ISW). This was a joint US-Russian ice camp that came very close to the presumed sinking location.

"It was set up from the (Russian ice-breaker) Akademik Fedorov on a multi-year drifting ice floe near 71.4° South," recalls Laurie Padman from the Seattle-based Earth & Space Research institute.

"The camp's track paralleled the last days of Shackleton's Endurance in 1915. I spent several weeks at ISW, my first Antarctic 'cruise', as US Chief Scientist.

"We collected atmospheric, sea-ice and ocean data for about four months, before ISW was recovered near 66° South by the (US icebreaker) Nathaniel B Palmer," he told BBC News.

Beyond the crew of the Endurance and the Ice Station, very few people have ever ventured into the west-central Weddell Sea, one of the most inhospitable parts of Antarctica.

NSF/USAP

NSF/USAP NSF/USAP

NSF/USAP