Walking in Shackleton's footsteps

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShackleton's escape from the Antarctic in 1916 is well told.

It is without doubt a remarkable story given the many challenges he and his crew had to overcome after losing their ship, the Endurance.

For months they drifted on sea-ice, before making a lifeboat dash to Elephant Island, followed by a hazardous sail across the Southern Ocean to South Georgia.

And if that wasn't enough, Shackleton and two colleagues then trekked over the mountains and ice fields of the British Overseas Territory to a whaling station to get help for the men stranded further back along the escape route.

Precisely how the explorer accomplished the last leg of the journey, across South Georgia, you can now follow in detail on a new map of the island.

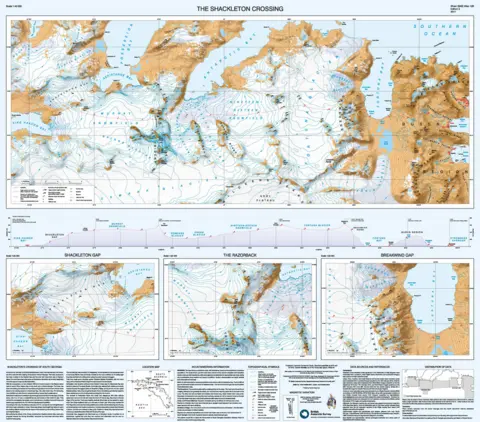

BAS

BASThe British Antarctic Survey (BAS) has updated its 1:200,000 rendering of the territory, with a special feature it calls The Shackleton Crossing on the map's B-side.

"We've never had a product like this before, and we've put a lot of effort into making it as detailed as possible," explained Laura Gerrish, a BAS mapping specialist.

"We've used stereo pairs of very high-resolution imagery to make the elevation data; and we've manually digitised all the rock and ice areas.

"We don't intend it as the route you must take, but it does show those who want to recreate the crossing the paths that are available," she told BBC News.

LANDSAT/USGS

LANDSAT/USGSThe Shackleton portion of the map is reproduced at 1:40,000 scale, with three insets at 1:25,000.

These illustrate the more dangerous parts of the 30km trek*, including The Razorback ridge and Breakwind Gap, which have near-vertical descents.

Shackleton, with Tom Crean and Frank Worsley, negotiated these obstacles by tobogganing on their coiled ropes.

BAS

BASIf the trio could retrace their steps today, they would be astonished at the changes that have taken place.

South Georgia is warming and its ice fields are in rapid retreat - something that has become very evident since 2004, the last time BAS updated the map.

"The data we have now is much more accurate of course, but there are many more new bays, coves, promontories and lakes, simply because the glaciers have retreated so much," Ms Gerrish said.

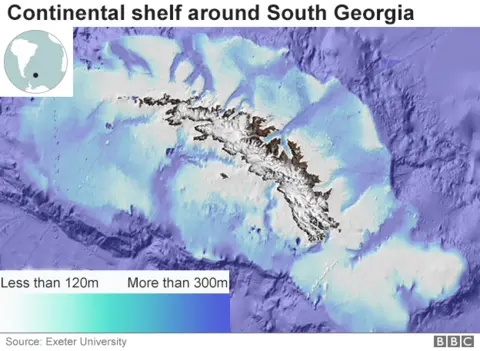

I wrote in March about the glacial history of South Georgia.

Some 20,000 years ago, during the last ice age, the island's glaciers pushed out 50km and more from their current positions, reaching to the edge of the continental shelf.

Now, the glaciers that formed that ice sheet are constrained to fjords, with some of the marine-terminating streams even pulling back on to land.

"I've been working at South Georgia for 15 years, and every time I go down I say to myself 'I can't believe the glaciers have moved again'," said Dr Mark Belchier, who is the South Georgia science manager at BAS.

Tony Martin/SGHT

Tony Martin/SGHTThe fastest retreating ice streams are on the northern or eastern coast - depending on how you want to describe the arcing territory. It's the "sunny side".

BAS

BASNeumayer and Nordenskjold, the two mighty glaciers that feed Cumberland Bay, have retreated 6km. But even on the south side, the changes are running at pace.

The 4km retreat of Twitcher Glacier since the last edition of the map has opened up a new bay. And with the next-door Iris Glacier also reversing, a new promontory has emerged.

Some of these features have yet to be labelled on the map. By the time the next edition comes out, the UK Antarctic Place-names Committee should have suggestions.

You may well be wondering what climate change means for South Georgia.

You often hear people who've been there describe it as a magical haven for wildlife. It is said that on some beaches during breeding season you literally cannot move for all the penguins and seals.

One benefit then of the ice retreat is that more breeding grounds will open up.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the other hand, the ice loss has big implications if there is a rodent infestation. A lot of money and effort has gone into ridding South Georgia of the rats that once attacked the ground nests of seabirds like the wandering albatross.

The glaciers acted as barriers that limited the rodents' range. If the rats come back - perhaps jumping off some tourist ship - they will find it much easier to get around.

"But just in general, a lot of the species on South Georgia are highly adapted to that relatively stable cold environment, and there's nowhere really for them to go if conditions change," explained Dr Belchier.

"And they could also be vulnerable to other species that invade from further north."

The new map was produced in collaboration with the expedition and advisory panel at the government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI).

It can be purchased from the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust. Much of the underlying data is also freely available to view and download from the South Georgia GIS portal.

RGS

RGS* The direct distance between Shackleton's landing point in King Haakon Bay and Stromness whaling station is just over 30km, but the men had to climb and descend 600m-high peaks, and at one point took a significant wrong turn.

[email protected] and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos