How much pocket money should we give our kids?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf parents can afford to give pocket money to their children, then much more often than not they will pay them in cash.

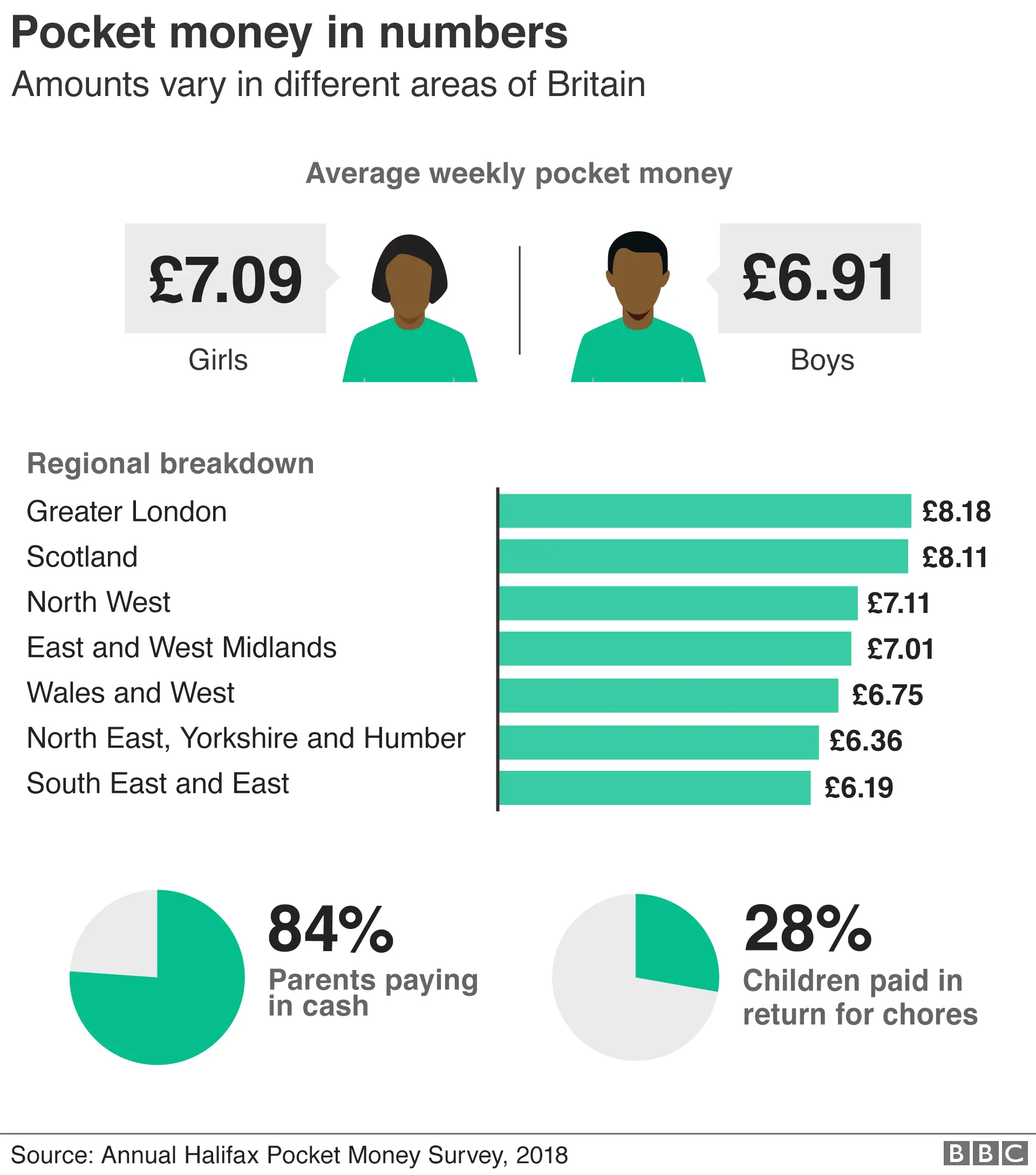

One survey suggests that 84% of British parents give notes and coins to their children, typically an allowance - including some discretionary spending - of £7 a week.

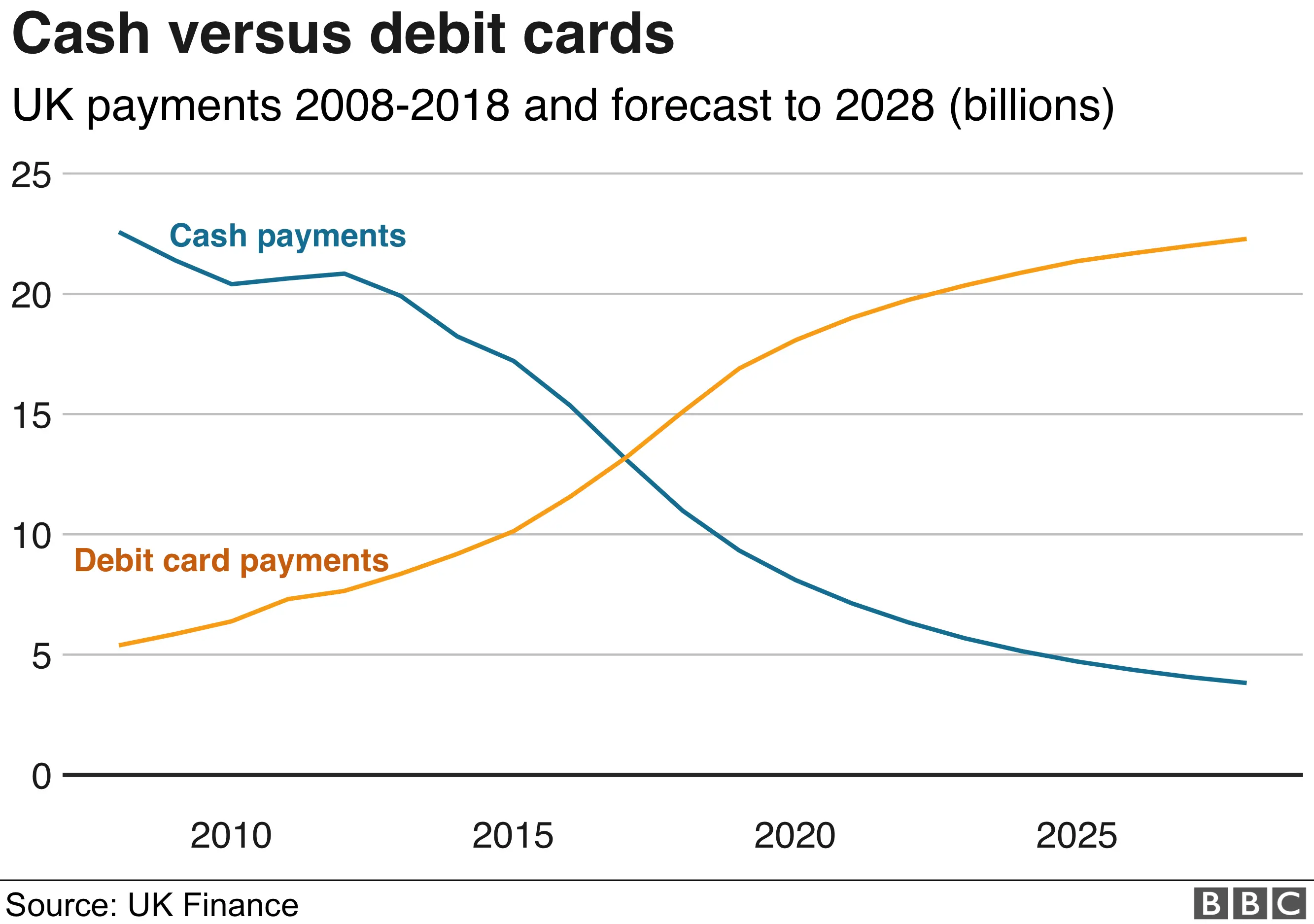

Yet, by 2028, banks predict that for every 10 occasions when adults buy something, they will only use notes and coins once. For the rest, we will mostly use cards or digital payments.

So what will that mean for the nation's children? Will today's youngsters be learning about money using currency that is close to obsolete? Will parents have to find a new way of paying pocket money, or decide not to bother paying at all?

Experts say that paying a small amount, however infrequently, can help youngsters learn about money and budgeting.

It seems that the children themselves agree, especially if pocket money depends on completing chores.

Nine-year-old Yusuf says: "It is making you feel like when you are older and get a job - when you do stuff and get paid for it.

"But obviously you are going to get more when you are older, rather than just 50p a day."

Pocket money surveys rarely agree on the going rate for children's allowances. The Halifax, part of Lloyds Banking Group, has been running such a survey since 1987, which is one of the most well-established.

Its latest findings suggested a wide range of average amounts in different parts of Britain. Others suggest the Halifax estimate of the typical weekly payment is rather high, but there is general agreement that cash is currently the preferred choice.

Research has suggested that money habits are set by the age of seven. At a meeting of head teachers and authorities on Wednesday, some will call for better financial education in primary schools.

Whatever children are taught at school, a few pennies at home - starting in cash - can go a long way, according to Sarah Porretta, of the government-backed but independent Money and Pensions Service.

Her advice for parents includes:

- Get children started with money as young as possible

- Don't worry how much to give in pocket money, or how often

- Parents who have no money at the end of the week should still talk to their children about the financial choices they make

For those parents who no longer carry cash - just using payment cards and smartphones - the mother-of-two says: "The trick is to go and get some coins, just so your children have the opportunity to interact with them.

"Then talk about what you are doing with money. If you are paying with a card or with a phone talk to children about that and link it back to those coins they have handled."

A growing band of pocket money smartphone apps suggest a different answer.

"The way we interact with money has changed. Pocket money is changing. We pay for things with the touch of a button," says Will Carmichael, father-of-two and chief executive of one of those apps - RoosterMoney.

"Traditionally pocket money sits in a jar at home, you add your coins, you can see it build up, and then you take that down to the sweet shop. That is no longer the case. You may use it for [video game] Fortnite online. You might use it to pay for a pair of trainers from an online shop.

"We are bringing pocket money online and making it more tangible again."

The app starts for four year-olds with an online reward chart, it moves on to a pocket money tracker which allows youngsters to set savings goals. Top of that list, according to the company's data, is Lego, followed by phones, and holiday money.

Eventually, it allows them to move on to spending with a pre-paid card. Data shows most pocket money is still spent on sweets, although books are second. The app also allows them to donate some of the money they have saved to charity.

However, the more advanced features cost a fee - an extra expense not suffered by parents who pay their children in cash.

Mr Carmichael argues that the charge costs parents far less than swimming or music lessons, but still teaches youngsters a practical life skill.

Bank basics

The next step for most youngsters is opening a bank account. Savings accounts can be opened from the age of seven, and current accounts from the age of 11.

"These are a great way of introducing your children to the world of banking, allowing them to use 'grown up' features like ATMs to get cash, or increasingly to make contactless payments, and even mobile payments if they have a smartphone," says Brian Brown, head of insight at data analysts Defaqto. "They also make it easier for family members to gift them money.

"Some of the accounts also pay interest, although not at high rates, allowing young people to get into the savings habit from an early age.

"By setting up standing orders you can pay children their pocket money regularly, with no moaning over missed or late payments - or even worse, each parent giving them their pocket money and paying them twice."