'It's terrifying': The Everest climbs putting Sherpas in danger

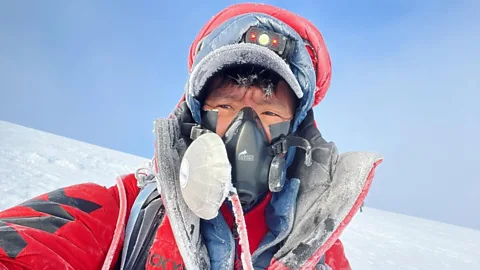

Dawa Sherpa

Dawa SherpaLong portrayed as "superhuman" guides and porters, Sherpas face many dangers in the mountains and are beginning to tell their side of the story. Are there ways to make their work safer?

The radio at Mount Everest Base Camp crackled once, then fell silent. Dorchi Sherpa, the base camp leader in charge, pressed the device against his ear, straining to hear another transmission. Outside his tent, the massive silhouettes of the high Himalayas cut into the dawn sky. Expedition tents dotted the rocky moraine below, buzzing with activity on 22 May, the busiest day of the 2024 spring climbing season.

"When I heard that final transmission, my heart sank," Dorchi tells me later, his face solemn as he recalls the moment. "The weather was clear, but something had clearly gone wrong up there."

The crackling message had been the last of several distressed calls from Nawang Sherpa, a 44-year-old guide who was leading Cheruiyot Kirui, a Kenyan climber, towards the summit of the world's highest mountain.

The tragedy unfolding that day shines a spotlight on an issue which, according to people working on Everest, has been ignored for far too long: the deadly risks and impossible safety dilemmas faced by Sherpas. The famous guides and porters of the Himalayas are, in the words of one Sherpa climber, often wrongly portrayed as "superhuman", as if they were untouched by altitude, effort and oxygen deprivation. But their legendary feats on Everest come at a huge sacrifice, as growing research, and interviews with climbers, doctors and officials, reveal.

So what exactly happened on 22 May 2024 — and what does it reveal about the bigger struggles over Sherpa health and welfare?

'The client seems unwell'

Like most tragedies on Everest, this one began with ambition, and, for the guide, economic need.

Nawang Sherpa, who was working for a Nepal-based trekking company, had begun his final push toward the Everest summit with Kirui. The term "Sherpa", now often used as a job title for any high-altitude guide in the Himalayas, originally refers to an ethnic group from Nepal's eastern highlands. Nawang Sherpa, and the other people with the surname Sherpa featured in this article, belong to that ethnic group, as well as being guides. Since mountaineering began in the region, Sherpas have carried the heaviest loads on Mount Everest, working first for colonial explorers, and later, for tourists.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKirui sought to join a rarified club of climbers reaching the summit without supplemental oxygen. Since 1953, when Everest was first summited, only around 2% of all successful climbs have achieved this, according to records from the Himalayan Database.

In his social media posts before the expedition, Kirui revealed his excitement about attempting this "pure" ascent, having previously conquered other mountains without oxygen assistance. The challenge of climbing without artificial support clearly represented a new frontier of adventure for the experienced mountaineer.

In those critical moments high on the mountain, when oxygen was offered, it remains unclear whether his refusal was a deliberate choice aligned with his stated ambitions or if his judgement had already been compromised by the impact of high altitude.

Dorchi Sherpa, the base camp manager, received a radio transmission from Nawang when they reached 8,800 metres (28,871ft). At that height, in what mountaineers call the death zone, the human body begins to shut down. With atmospheric pressure at a third of sea level, each laboured breath delivers barely enough oxygen to sustain basic bodily functions.

"The client seems unwell," Nawang Sherpa's voice crackled through to Base Camp at 08:07, wind interference fragmenting his words as he reported to Dorchi.

"Oxygen," came Dorchi Sherpa's immediate response. "Put him on oxygen and begin descent."

According to Dorchi Sherpa, Nawang pleaded with Kirui for several minutes to accept the supplemental oxygen canister from his pack. Kirui refused, Dorchi says. "No oxygen," he repeated with growing agitation. "No oxygen. Pure summit only."

By 09:23, when Nawang Sherpa's voice returned over the radio, fear had replaced concern. "Cannot move him," he reported. "He becomes... angry. I cannot drag him down alone."

For the next two hours, Kirui refused the supplemental oxygen that Nawang Sherpa repeatedly urged him to use, according to Dorchi Sherpa. Despite showing clear signs of altitude sickness, including confusion and slurred speech, the Kenyan climber remained determined to continue his ascent without artificial air.

This impasse proved fatal. Both men died on Everest. Their bodies are still there: the Kenyan climber's body remains at the same location where he was last seen, while Nawang's body has not been located. (Read more about why it is so difficult to recover bodies from Everest.)

It's unclear what exactly happened in those crucial last moments – and in all likelihood, we will never know. Certainly, everyone started the journey with the best intentions. Kirui's girlfriend, Nakhulo Khaimia, describes the trip as a long-held dream for him, which he prepared for carefully.

"He poured his time, energy, and entire lifestyle into it," she says. "His social life revolved around getting ready for Everest. His journey was intentional, disciplined and deeply personal."

James Muhia, who was not on the Everest expedition but had climbed with Kirui on an expedition to summit another mountain without oxygen, says he believes his friend had an oxygen cylinder with him to use in case of an emergency. "Whether he used this emergency bottle or not, we cannot tell," he says.

For his part, Nawang was an experienced mountain guide who had never been to the summit of Everest before but had summited other tall peaks in the Himalayas, according to his family. But those working on the mountain warn that a number of factors, including the conditions Sherpas work in, can make these kinds of deadly situations especially complicated, and difficult to resolve safely.

Spotlight on Sherpas

According to Sanu Sherpa, a veteran guide who holds the distinction of being the only person to have summited all 14 8,000m (26,247ft) peaks twice, Nawang's death represents no isolated tragedy but rather, a predictable pattern in high-altitude mountaineering.

I spoke to Sanu Sherpa at his flat in Kathmandu, as he was preparing for his 45th summit of an 8,000m peak. Despite having twice climbed all 14 of the world's highest mountains, he speaks not of personal glory but of professional obligation.

"I don't think Nawang was being reckless or foolish," he says. "He was being exactly what we've all been trained to be, responsible to the end. The tragedy isn't just that he died, but that dying was the most professionally appropriate choice he could make."

Sanu Sherpa

Sanu SherpaOn Everest and other Himalayan giants, such tragedies involving Sherpas unfold annually with little public attention, says Sanu Sherpa, creating a growing ledger of sacrifices made in service to foreign ambitions.

A complex web of professional expectations shapes guides' decisions and can place them in great danger, when paired with the inherent risk of undertaking strenuous work in an extreme environment, studies suggest. Sherpa guides often find themselves caught between traditional values of service, the economic pressures of an industry where guides are hired based on their personal reputation, and the life-or-death realities of working at extreme altitude, with client satisfaction frequently prioritised over personal safety.

The tragedy highlights the risk Sherpas like Nawang take on when they agree to accompany a client.

Working as a guide or porter on Everest offers a rare economic opportunity in one of the world's poorest regions, but demands a toll unmatched in any service profession, where workers routinely sacrifice their well-being in service to their clients. When tragedy strikes, Sherpas often vanish from the story.

According to the Himalayan Database, the ledger-keeper of the human death toll in mountaineering, 132 climbing Sherpas have perished on Everest's slopes, 28 in the past decade alone. They fell in crevasses, were crushed beneath collapsing seracs (huge towers of ice), or simply vanished into the mountain's vastness while tending to their clients.

While foreign climbers may view these hazards as acceptable risks for their singular attainment, for the guides and porters on Everest, the data presents a stark workplace reality: 1.2% of these workers die on the job, an extraordinary occupational danger by any standard measure.

In the past, that risk to Sherpas was often downplayed, and instead, foreigners tended to highlight Sherpas' strength and resilience. It's a portrayal the Sherpas themselves are starting to openly challenge.

Dawa Sherpa, the first Nepali woman to summit all 14 8,000m (26,247ft) peaks, highlights a dangerous misconception about Sherpas having superhuman abilities. She's witnessed the physical toll: guides supporting struggling clients for hours, preparing high-altitude meals, and rationing their oxygen so clients can continue climbing.

"They aren't superhumans. Sherpas often push themselves beyond safe limits while prioritising others' summit goals," Dawa Sherpa says. "I've seen them return with frostbite or oxygen deprivation because they sacrificed their safety for someone else's achievement."

She notes that wealthy climbers sometimes hire multiple Sherpas per expedition and, when exhausted during descent, expect to be physically assisted downward. This dynamic, she emphasises, makes the mountain even more hazardous for those carrying the heaviest burden.

Unequal power

When talking about the dangers they face, Sherpas interviewed by the BBC keep returning to the fundamental problem of the dramatically unequal power balance: the guide's inability to refuse a client's dangerous requests, even when their health is at risk, for fear of losing work and income.

"Sherpas don't climb for the fame and glory of it, nor for some accomplishment. They climb because it is sometimes the only source of livelihood. That fundamental reality shapes every decision made on the mountain," says Nima Nuru Sherpa, president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association (NMA). The association provides training programmes for guides and porters to improve safety standards and professional qualifications.

"These systemic constraints help explain why guides like Nawang make the choices they do," Nuru Sherpa says. "The professional consequences of abandoning a client, potentially losing future work in a reputation-based industry, likely weigh as heavily as immediate safety concerns in those oxygen-deprived moments of decision. When your entire family depends on your work as a mountain guide, walking away becomes nearly impossible."

Meanwhile, the Sherpas' own extraordinary achievements tend to attract little attention. In May 2025, Nepali Sherpa Kami Rita broke his own record for the most climbs of Mount Everest, when he scaled the world's tallest peak for the 31st time.

Sanu Sherpa says that his accomplishments remain largely unrecognised even within Nepal itself, whereas far lesser feats by foreign mountaineers often receive greater celebration and financial rewards.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCarrying champagne up Everest

The unequal relationship between Western climbers and Sherpas was born in the shadows of colonialism. When British expeditions first approached Mount Everest in the 1920s, they recruited local men as "coolies", a term borrowed from colonial India – to carry their extensive gear, which included everything from silver cutlery to cases of champagne. These early Sherpas received little recognition. Their names rarely appeared in expedition accounts, except when catastrophe struck. In his chronicles of one of these early expeditions, British adventurer George Mallory mentioned them primarily when seven porters died in an avalanche – the first recorded Everest fatalities.

By the mid-20th Century, as mountaineering shed its imperial trappings, the dynamic began to shift. Tenzing Norgay's 1953 summit alongside Edmund Hillary forced a reluctant recognition of Sherpa skill, after the international press initially downplayed his achievement, portraying him as an admirable sidekick and a cheerful companion to the heroic Hillary.

The commercial era dawned in the 1980s, recasting Everest into a marketplace and Sherpas into essential service providers. As wealthy clients with limited technical skills began pursuing the summit, Sherpa responsibilities expanded dramatically. No longer just load carriers, they became guides, safety technicians, and sometimes rescuers, roles that demanded greater skill but came with limited additional authority. Western expedition leaders maintained decision-making power while Sherpas shouldered increasing physical risk.

Disaster marked a turning point. When, in 2014, 16 Nepali workers died in a single avalanche while preparing the route for commercial clients, Sherpas across Everest staged an unprecedented work stoppage. Their collective action forced a reckoning with the industry's inequities and led to modest improvements in insurance coverage and compensation.

Experts warn that the root of the problem is the power imbalance between guides and clients, in an extreme environment where one's thinking becomes clouded from the altitude, and every wrong decision can be fatal. The result, they tell the BBC, is an industry that has normalised life-threatening conditions as simply part of the job description for guides, who must routinely place themselves in mortal danger to satisfy their customers' aspirations.

Brain fog

In Dingboche, at 14,470ft (4,410m) on the trail to Everest Base Camp, expedition medical officer Abhyu Ghimire moves between examination rooms in the Mountain Medical Institute. Outside his window, the jagged peaks of Ama Dablam rise against a cerulean blue sky. It's expedition season, and his days stretch from dawn until well after dusk. Having summited Everest himself and worked as a medical officer for almost a decade, he's witnessed firsthand how altitude transforms both mind and body. The effect can further complicate the client-guide dynamic, his insights suggest – and put lives at risk.

"The brain gets pretty foggy at high altitude," he explains in a video call between patient consultations. "The brain is meant to function at 99% oxygen saturation at sea level. Up there, even 50-60% oxygen saturation is frequently seen."

This cognitive deterioration, invisible but potentially deadly, transforms personality and decision-making in ways that defy rational explanation. "The brain functions far under capacity and decision-making becomes grossly altered," says Ghimire. "This can even lead to hallucinations."

The transformation can be profound and disorienting: "[Even] your best friend at that altitude can trigger such intense reactions up there, that if someone simply asks you to pass a water bottle, you might throw it at their face. Someone familiar becomes a stranger," he explains.

According to Ghimire, Kenyan climber Kirui would have experienced progressive cognitive breakdown as he pushed higher without supplemental oxygen. By the time Nawang Sherpa radioed base camp to report his client seemed unwell, Kirui's rational thinking centres would probably have effectively shut down, Ghimire says. Kirui's apparent refusal of supplemental oxygen is in line with a known paradoxical effect of hypoxia (oxygen deprivation): the more oxygen-deprived the brain becomes, the less capable it is of recognising its impairment.

Nawang Sherpa's own judgement would have been increasingly compromised by altitude despite his use of supplemental oxygen, Ghimire says, as such bottled oxygen is not enough to provide the climber with sea-level oxygen conditions – instead, it only gives them about as much oxygen as they would have at roughly 6,000 – 7,000m (19,685 – 22,966ft) altitude. This limited oxygen supply, along with the exhaustion, potential dehydration and extreme cold the guide faced, could have diminished his own mental clarity, Ghimire says. In addition, Nawang Sherpa would have faced what Ghimire describes as a common problem: "Many times, clients facing hypoxia become difficult and refuse to listen to what their guide tells them".

Lurking danger at lower altitudes

The health challenges facing Nepal's mountain workers extend far beyond the crisis moments above Base Camp. The everyday physical toll begins much lower on the mountain, accumulating over the years of service.

"At altitudes above 4,000m (13,123ft), staying for extended periods can cause chronic mountain sickness," Ghimire explains. This condition, known medically as Monge's disease (or Chronic Mountain Sickness), manifests as a triad of dangerous symptoms: "polycythemia, where the blood becomes dangerously thick, pulmonary hypertension, where the lungs become pressurised, and chronic hypoxia, which is persistently low oxygen in the blood," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are also different risks for Sherpa and non-Sherpa guides. Ethnic Sherpas possess generations of genetic adaptations to altitude, while workers increasingly recruited from other Nepali groups lack these biological advantages, Ghimire says. This distinction matters medically, as those without altitude adaptations face substantially higher risks while performing identical work in oxygen-depleted environments.

The population dynamics of the Khumbu region compound these risks. "Many people from lower elevations come here seeking employment," Ghimire says. "They migrate to high altitude but lack the two genes that have been studied that would make them more robust to these conditions. They're forced to spend long periods at high altitude, which causes heart problems, blood issues, vitamin D deficiency, and numerous other health problems."

According to Nima Ongchuk Sherpa, a physician from Khunde, three porters from lower regions have already lost their lives to altitude-related complications this year, all even below base camp.

More support for Sherpas?

In the Department of Tourism headquarters in central Kathmandu, Rakesh Gurung, the former director of the mountaineering section, speaks with measured concern. Seated behind a weathered wooden desk in a modest government office, where climbing permits are processed and expedition regulations are drafted, he reflects on the industry's challenges.

"There's a systematic failure in being able to provide Sherpas with the safety they deserve," he acknowledges. "While we have basic regulations in place, creating and enforcing a comprehensive code of conduct has proven incredibly difficult. The industry is fragmented, with dozens of operators competing on price rather than safety standards."

He says the tourism department lacks both the resources and specialised expertise to effectively monitor what happens at extreme altitudes. In addition, Nepal's constantly shifting political landscape makes it difficult to come up with an effective plan, he says. "We've had multiple different governments in the past decade alone, consistent policy development has been nearly impossible. Each new administration brings different priorities to tourism management."

This power imbalance extends beyond individual guide-client relationships to the regulatory framework itself, as well as the economics of high-altitude labour. A veteran Sherpa guide might earn between $5,000 and $12,000 (£3,788 and £9,092) in a climbing season, which is substantial in a country where annual per capita income hovers around $1,399 (£1,060). But these earnings support extended families and come at extraordinary physical risk. When tragedy strikes, the financial safety net remains inadequate, guides say.

"What's missing is any sustained reckoning with the structural inequalities that keep Nepal tethered to this dangerous economy, and the absence of real alternatives," says Nima Nuru Sherpa, the president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association. "When a community has limited options, the mountains become not just our backdrop but a necessity, regardless of the physical toll."

The government recently increased mandatory life insurance for high-altitude workers to approximately $14,400 (£10,825), but guides say this falls short of compensating dependent families for a lifetime of lost income and care. Nawang Sherpa's family received this standard insurance payout after his death, with his employer pooling additional resources to provide some supplementary support.

Tshiring Namgyal

Tshiring NamgyalEven basic safety regulations prove difficult to enforce in the world's highest workplace. According to the Department of Tourism, Nepal's mountaineering regulations, solo ascents above 8,000m (26,247ft) are explicitly prohibited, for safety reasons. Yet each season brings high-profile climbers attempting precisely such feats, with little consequence.

Sandesh Maskey, an expedition officer at the Department of Tourism, says that climbers are banned from scaling Everest solo. "We haven't given [solo climbers] any permission to do this solo. It is unethical and they will be going against the law if they do so."

"We expect climbers to be ethical, but people with power and money break rules because they know that once they're on the mountain, we have no practical way to monitor or stop them," he says. "Once climbers move above Base Camp, traditional oversight mechanisms become impractical."

This spring, in response to mounting safety concerns, the Department of Tourism implemented new regulations for the 2025 climbing season. All expeditions to peaks above 8,000m (26,247ft) must now maintain a ratio of one guide for every two climbers. The department has also made reflector technology devices mandatory for all high-altitude expeditions to aid in locating missing climbers. But Sanu Sherpa, the experienced guide in Kathmandu preparing for his next expedition, is doubtful that this will change things – given how hard it is to enforce these rules on Everest.

As he prepared to embark on another expedition up Everest the next day, he admitted he was always on the verge of quitting his job. "It's terrifying with four kids and their lives fully dependent on me. They ask me why I climb the mountains at all."

--

This story was updated on 02/06/2025 to make it clear that Cheruiyot Kirui had not previously ascended Mount Everest without oxygen.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.