What the Mesopotamians had for dinner

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Ancient Babylonia, soups and stews reigned supreme. Food historians are now using taste-tests to recover their forgotten flavours.

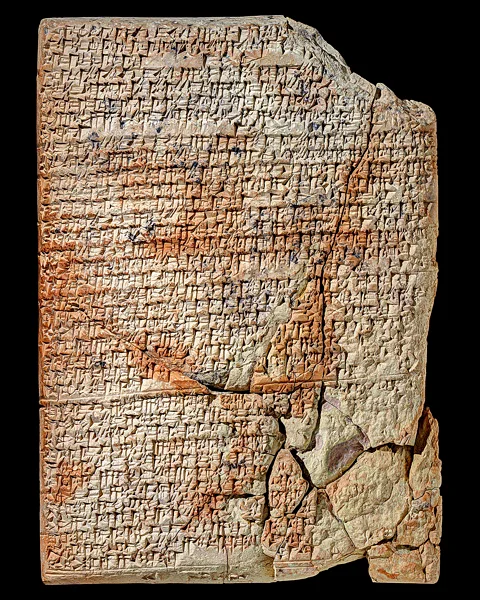

No-one knows exactly where they came from; for a long time, no-one really understood what they said. The little slabs of clay covered with dense, wedge-shaped cuneiform writing were thought by Yale University scholars to involve medicines. Unearthed in an archaeological dig in the Middle East, they have probably been in the Yale Babylonian Collection since 1911. It wasn't until the early 1980s, however, that French scholar Jean Bottéro finally figured out what the tablets were saying. In their understated way, for nearly 4,000 years, they've been talking about dinner.

The four tablets – the larger ones the size of a large bar of soap, the smallest, more than a thousand years younger, a mere round handful of clay – are inscribed with the ingredients not of pharmaceuticals but of dishes. Dated to at least 1730 BC, the three larger tablets mostly contain descriptions of stews; the smallest, from a later period, speaks of a broth.

The mere fact of their existence is a mystery. In ancient Mesopotamia, people rarely wrote about preparing food, said Agnete Lassen, the assistant curator of the collection. "Out of hundreds of thousands of cuneiform documents, they are the only food recipes that exist," she said. "We don't have an explanation."

Courtesy of Peabody Museum

Courtesy of Peabody MuseumAnd indeed, in many cuneiform texts, when ancient scribes put stylus to clay and incised stories and accounts that happen to mention food, they use words that are themselves sometimes mysterious to modern scholars. Ingredients pop up whose identity is still unknown, said Gojko Barjamovic, an Assyriologist at Harvard University. Asum is myrtle, salu is cress seeds, but what is hurrium? Reading the list of unknown spices alone, from a paper by Barjamovic, Lassen, and their collaborators, conjures visions of a lost garden, nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers: Kurullu, kuruš, nīnu. Silaru, zanzar, zibibianu.

The Yale culinary tablets, as the four slabs of clay are known, have the same curious assumption as many recipes do, ancient or modern: the writer expects that the reader basically already knows what they are aiming for. The instructions are terse, clipped. And as is the case for many old recipes, from all vintages of the human relationship with cuisine, amounts are not specified.

With all of this lying between us and the experience of dinner in Babylon long, long ago, it can be difficult to imagine clearly what the food was like. But some years ago, Barjamovic, Lassen, and their colleagues, including Iraqi food historian Nawal Nasrallah, made some gestures in that direction. They updated the translations of recipes made by Bottéro, using new understandings of some words. They performed careful experimentation, altering ingredients one by one.

They could eliminate one potential ingredient by virtue of the fact that it made the resulting dish unbearably bitter, to the point where none of the other carefully incorporated seasonings were detectable. While it is possible that this was the intended effect, it doesn't seem likely.

It is striking, however, that stews and broths make up the entirety of the recipes, Nasrallah, author of the cookbook Delights from the Garden of Eden, has noted. Stew – meat and vegetables in a broth – is a staple of modern Iraqi food. It was also a major feature of food in medieval Iraq, described in a 10th-Century cookbook Nasrallah has translated. And when the research group cooked their updated and tested translations of four of the culinary tablet recipes, they yielded something that must be at least redolent of that long-ago tradition.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHere is how one of the stews is made: for the lamb stew known as tu'hu, first you get water. Then you sear leg meat in fat. In go salt, beer, onion, rocket, coriander, Persian shallot, cumin, beets, water. Crushed leek and garlic and more coriander, for a fiery taste. Then add kurrat, an Egyptian leek. The beets turn it an electric red, and of the four, it's Lassen's favorite. "It's pungent and it's very nicely spiced," she said. "It has good flavours."

Even with all this care, there remains the fact that people's tastes might have been quite different back then. A famous example of a food that is not so popular on the far side of several millennia is the Roman fish sauce garum– this potent, fermented, umami goo is not a common part of modern Italian cuisine. The researchers acknowledge this difficulty: using the tastes and impressions of people alive today to try to set bounds on what dishes this old taste like is a fraught business.

More like this:

• The food that could last 2,000 years

Between then and now, Islam also arrived in the Middle East, making pork a less popular ingredient, and the Colombian Exchange (the trade between the Americas and Europe from the 15th Century) brought tomatoes and potatoes from the New World. Modern Iraqi cuisine is not a replica of what was eaten in Babylon.

Who knows if, 3,000 years from now, people sat where you are now will be eating anything like what you have today? In a modern food system where what we eat is not particularly dependent on where we are, it feels like the connection between food and local geography has evaporated.

Thousands of years from now, on the far side of who knows what changes, perhaps that link will have returned. Perhaps the climate will be so different that the British Isles will be growing lentils. Maybe in what was once Siberia there will be a booming business in coconuts.

Barjamovic points out that as far as these ancient recipes are concerned, the story is also not over. Each archaeological field season brings with it the possibility of new texts being dug up, shedding new light on mysterious words for spices and other ingredients. The Mesopotamian way of thought was not copied or passed on as Greek texts were. It fell out of human knowledge in the 1st Century BC. "But because they wrote in clay," he said, "it's there in the soil, indestructible."

* An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that aubergines were brought from the New World. This has been corrected as aubergines are thought to have been originally domesticated in China and India, and some wild relatives have been found in Africa.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and X.