Where we might find aliens in the next decade

Nasa/JPL

Nasa/JPLForget UFOs and alien abductions, here's how scientists are really looking for life on other worlds.

It is easy to wax lyrical about aliens. The prospect of life on other planets has shaped much of our culture and continues to inspire books, TV shows, movies – and the odd conspiracy theory of course. But amongst all the fantastical visions of little green men there is a real, actual hunt for alien life taking place right now, and it is not some fringe science or controversial idea. It is a systematic process that scientists are undertaking, with results expected in as little as a decade.

To be more exact, there are multiple hunts for alien life currently underway. On Mars, a rover is collecting samples that may determine if life ever existed on the red planet. Probes are visiting some of our solar system's icy moons to search for signs of habitability. Astronomers are also beginning to scour the atmospheres of planets beyond our own solar system for telltale elemental cocktails that hint at alien life. And, yes, we are even keeping a beady eye out for signals from any intelligent civilisation that might purposefully – or accidentally – make contact.

"I think in 10 years we'll have some evidence about whether there's anything organic on some nearby planets," says Lord Martin Rees, the UK astronomer royal. "I think we are really [on the cusp]."

Alien life, if it exists, has not made itself easily known. Early attempts to search for extraterrestrial intelligence, called Seti, began in the mid-20th Century, with astronomers looking in vain for radio signals on other planets. Mars, which was believed in the late 19th Century to have life-harbouring canals and rivers, was discovered to be a mostly dry, barren wasteland. Planets around other stars, meanwhile, were so small that finding them was difficult, let alone learning much about them.

To hunt for alien life we have had to fine-tune how we search for it, and prepare for the possibility that any initial detection is likely to be perhaps somewhat small – evidence of microbes or chemical markers in a distant atmosphere. Compared to the Hollywood vision of first contacts with extra-terrestrial life, it might seem anticlimactic, but hard evidence that life exists beyond the boundaries of our own planet will still fundamentally alter our view of our place in the Universe.

Nasa

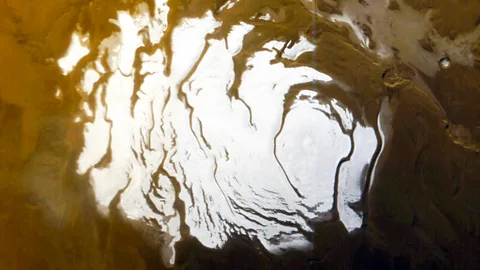

NasaIn our solar system, Mars is arguably the most popular destination to hunt for life, at present. We know the planet was likely wet and potentially habitable billions of years ago, with seas and lakes on its surface. More recently scientists have even found tantalizing clues that there may be liquid water on Mars still, hidden beneath the planet's southern ice cap.

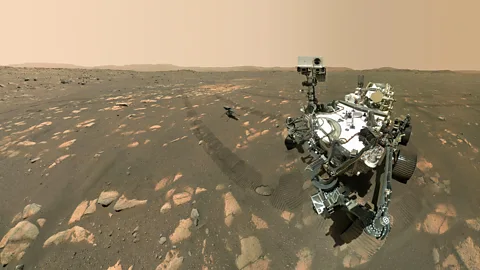

Currently, Nasa's Perseverance rover is scooping up samples from the now-dry bed of what was thought to be once a lake in a region called Jezero Crater, just to the north of the Martian equator. The goal is to collect dozens of samples and return these to Earth in the early 2030s – a mission known as Mars Sample Return – where they can be investigated in detail for signs of life. The mission is currently facing difficulties, with the return aspect struggling for funding. But if they can pull it off, there are scientific riches in store.

Susanne Schwenzer, a planetary scientist at The Open University in the UK and a member of the Mars Sample Return science team, says the presence of past life on Mars could leave a fingerprint in the interaction of its rocks and water. "If you have life, things look very different," she says. "If we have the samples from Mars, we can go into miniature detail to study these processes."

It's possible some of the samples could even contain fossilised microbes inside the rocks. "I as a scientist wouldn't have spent my life on this if I weren't hopeful that we have a good chance of finding something," says Schwenzer. "I hope we will find something, but I can't predict it."

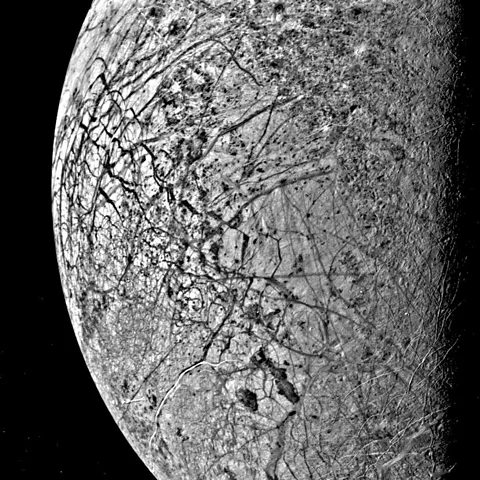

But even if signs of life on Mars were to be detected, it would not be unequivocal proof of widespread alien life elsewhere in the universe. Mars and Earth are known to have shared material early in their history, meaning they might also have shared the genesis of life. For evidence of a true second genesis, proof that life arose for a second time independently on another world, scientists are looking to the solar system's icy moons such as Jupiter's Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, thought to contain vast oceans beneath their frozen surfaces. "If we were to find life on the icy moons, we would be sure this is a different genesis of life from Earth," says Schwenzer. (Read more about what life in alien oceans might be like.)

A Nasa spacecraft called Europa Clipper is due to launch to Europa in October, following a European spacecraft, Juice, which launched in April 2023. Set to arrive in 2030 and 2031, the two spacecraft are not likely to detect life on Europa. But they will study the extent of its ocean, and set the stage for a future mission that might try to burrow beneath the ice sheet – such as an ongoing Nasa proposal called Europa Lander that remains on the drawing board – or fly through plumes that might be ejected from the moons' oceans into space, to look for life.

Actually getting a machine into the ocean of one of these worlds is a "100-year-problem", says Britney Schmidt, an astronomer at Cornell University in New York, because of the difficulties of getting through the multi-kilometeres-thick ice. But "getting into the ice shell and interacting with liquids is something we could do" more near-term, she says. "That's the kind of mission I would like to see happen. Our group is working on instruments and technologies so we know when we get there what to do."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf you aren't quite ready to wait 100 years, then you might want to cast your gaze to other solar systems. We now know of more than 5,500 planets around other stars, known as exoplanets, and more continue to trickle in every day. With the immense power of new telescopes, most notably the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers are now beginning to probe some of these planets in exquisite detail.

In particular, they are using JWST to see if they can work out what gases are present on some rocky exoplanets similar to Earth. JWST was not initially designed to study exoplanets when it was first drawn up at the turn of the century, but it has since been re-tasked with studying these worlds, being the largest space telescope in history and thus our best machine to do so.

It cannot study Earth-like worlds around stars like our Sun. These planets are simply too dim against such bright stars for even JWST to study, and will require a more advanced telescope such as Nasa's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set to launch in the 2040s to investigate them. But JWST can study planets around small stars called red dwarfs, and right now it is flexing its capabilities with a fascinating system called TRAPPIST-1, which contains seven Earth-sized worlds. At least three of the planets orbit in the star's habitable zone, where liquid water – and life – could exist.

The first step is for astronomers to confirm if these planets have atmospheres. Research with JWST to make this determination is currently underway, with results expected later this year or in 2025. Initial results have shown that the innermost planet likely lacks an atmosphere required for life, but if atmospheres can be found on the other TRAPPIST-1 planets it would be a monumental discovery says Jessie Christiansen, an astrophysicist at Nasa's Exoplanet Science Institute at the California Institute of Technology in the US. "The next 20 years of exoplanet search will depend on that result," she says. "If red dwarf planets have atmospheres, we will point every telescope on Earth at these planets to try and see something."

If we can find those atmospheres, JWST will be used to look for signs of biosignatures in atmospheres that might hint at life. "We'll be looking for disequilibrium chemistry," says Christiansen. "You can make carbon dioxide, methane, and water on [any] planet. But having them in ratios where they can't be maintained naturally, that's where you start to say biology is involved."

Future telescopes, like the Habitable Worlds Observatory and a European proposal called Life, will then try to perform this same analysis for true Earth-analogue planets around stars like our Sun. "The driving planetary class will be rocky planets in the habitable zone," says Sascha Quanz, an astrophysicist at ETH Zürich in Switzerland who leads the Life program.

And then there's the hunt for intelligent life. Jason Wright, an astronomer at The Pennsylvania State University in the US, says much of the low-hanging fruit has been picked. Radio observations have shown that, within about 100 light-years of Earth, powerful beacons pointed in our direction "don't seem to exist", says Wright. Now, programs like Breakthrough Listen in the US are casting their gaze further afield. They are looking for directed radio signals coming from more distant planets in our galaxy, and are even starting to look for accidental communications leakage from planets like that which is emitted from Earth.

You might also like:

Upcoming telescopes, most notably a vast new radio telescope set to come online in 2028 called the Square Kilometer Array, a group of thousands of radio antennas spread across two continents, should significantly expand this search. "That's really exciting," says Wright. But even with modern radio telescopes a detection could come "at any moment", says Wright.

Nasa

NasaIf we do find evidence of alien life, whether that's in our solar system, on an exoplanet, or from an intelligent civilisation, that evidence is unlikely to be a slam-dunk. It will more likely be a gradual process to the point where life seems like the most likely explanation. "The more information you have, the more you're in a position to rule out false positives," says Quanz.

Thus, the discovery of alien life might not be a single defining moment. How the public reacts to that possibility is an interesting question, says Rees. "If it's tentative, that should be made clear by the scientists," he says. "One hopes it would be reflected in any newspaper reports." Recent examples include the detection of phosphine on Venus and dimethyl sulfide on an exoplanet, both hotly debated hints of biology that remain extremely uncertain.

There remains the other possibility, too, that all of these searches will turn up empty. That in itself will be an interesting scientific result, telling us that alien life – if it exists at all – is not common in the Universe. "A null result tells you something fundamentally important" about life, says Quanz. "Maybe it's really rare."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.