The mathematical muddle created by leap years

Alamy

AlamyEvery four years we have a 29 February – apart from those that fall at the turn of a century, unless the year is divisible by 400. This is the messy story of how leap years work.

I have a friend at work – in the mathematics department of the University of Bath in the UK – who is turning 11 this year. He's not a child prodigy (although we definitely do get some of those in maths). He just has a very special birthday: February the 29th.

As 2024 is a leap year, it means he gets to celebrate on the actual date of his birth instead of one of the surrounding days. Although for my colleague it is undoubtedly tedious to have people like me joke about how old he is (and spare a thought for the 100 year old "leaplings" who have had to endure 25 such occasions), for the rest of us the leap year has a special, almost mystical, aura about it.

This exceptional day has been associated with all sorts of weird and wonderful traditions over the years: from the wildly outdated notion that 29 February is the only day when women can propose to men, to the Leap Year Festival held in Anthony, New Mexico, which sees people born on this special day gather to celebrate their rare birthdays together.

As a rule of thumb, leap days come around every four years. But there are exceptions to this rule. For example, at the turn of every century we miss a leap year. Even though the year is divisible by four, we don't add a leap day in the years that end in 00. But there's an exception to this rule too. If the year is a multiple of 400 then we do add in an extra leap day again. At the turn of the millennium, despite being divisible by 100, the year 2000 did, in fact, have a 29 February because it was also divisible by 400.

So far so complicated. But why do we have leap years at all? And why are the rules that govern them so convoluted? As you probably know, the answer is something to do with keeping things in sync.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are only two fundamentally determined units of time for our planet. One of them is the day: the time it takes for the earth to spin once on its axis, from facing the Sun, to facing away and then back again. The other is the year: the time it takes the Earth to complete one orbit of the sun.

What are the odds of being born on a leap day?

If leap years came around every four years exactly (which they have done for the last 120 years, covering the birthdays of everyone who is alive today) then the probability of being born on a leap day would be one in 1,461. This means there are probably around 5-5.5 million leaplings in the world right now.

By coincidence you get a similar number – 1,440 – of extra minutes in a leap year – so that's roughly one extra minute per day of the four year cycle (this because the Solar year is roughly 349 minutes longer than 365 days, so almost an extra minute per day for each day of the year).

Annoyingly it takes the earth 365.24219… (roughly 365 and one quarter) days to rotate around the sun and return to its starting position. So, a true solar year is not actually 365 days long. This is very inconvenient. We can't celebrate New Year at midnight one year and then at 6AM the next and midday the year after that – getting further and further out of sync.

Way back in 46 BCE, Julius Caesar recognised this problem and with his advisors decided on a clever solution to improve the running of his Julian calendar – which included adding the extra quarter days accumulated every four years to create a whole extra day. (Read about how the leap year was invented under Caesar, and refined by Pope Gregory in the 16th Century.)

Adding a day every four years, however, gives the average length of a year to be 365.25 days – a little bit too long.

When the Gregorian calendar was introduced, it was decided to improve the approximation by striking out one of the leap days in years divisible by 100. Under this system, over the course of a century we would add 24 extra days not 25, making the average year 365.24 days long – an (even smaller) bit too short.

Not satisfied with this better approximation, it was decided to add back in an extra leap day every 400 years. Over the course of one 400 year period, this entails adding in 97 extra days in total, making the average year length 365.2425 days – near enough that no-one could be bothered going further.

Alamy

AlamyTo leap or not to leap?

This is how the Gregorian calendar calculates leap years:

This system keeps the calendar aligned with the Solar year to within a few decimal places of accuracy.

It took several attempts and false starts to get to our present-day calendar accuracy. To get to the next level of accuracy we'd need to remove leap days on years that were multiples of 3200. That would give us an extra 775 days over the course of 3200 years making the average year 365.2421875 days long – an even greater level of accuracy.

This seems like a lot of trouble to go to, just to make sure that days align with years. Why instead don't we just change our definition of the year to make it exactly 365 days? This seems like a sensible solution, and indeed it would be, were it not for the axial tilt of the earth.

The "Big Whack" theory suggests that about 4.5 billion years ago, a huge collision between proto-Earth and another, Mars-sized, planet sent enough debris flying to create the Moon, but also caused the Earth's axis to tilt. Although that tilt is thought to have varied over the years, the fact that we have a tilt at all gives rise to the seasons familiar at higher latitudes – summer when your part of the Earth is tilted towards the Sun and winter when it's tilted away, with spring and autumn in between.

If we didn't make adjustments for the leap days then our calendars would get out of sync with our seasons. After 100 years the calendar would be off by about 25 days. After about 750 years, those living in the northern hemisphere would be celebrating Christmas in the middle of summer and Valentine's day in the autumn. And that just wouldn't do. Indeed, this lack of alignment between the civic and solar calendars was what prompted Caesar to add in the leap day in the first place, as well as introducing a 445-day year in 46BC to correct the months-long lag that had built up. (Read more about the longest year in history.)

You may well have heard of leap seconds. You might well ask why we can't just add in a few leap seconds every day so that we end up with the right number of extra hours by the end of each year? It's a nice idea, but of course it would mean that, by extending the day, our clocks would get out of sync with our daylight, which would be an even worse problem. Halfway through the year we might end up eating breakfast at dusk or going to bed at sunrise. In fact, leap seconds are used to avoid exactly this problem – small variations in the period of Earth's rotation on its axis that would otherwise throw our time out of kilter.

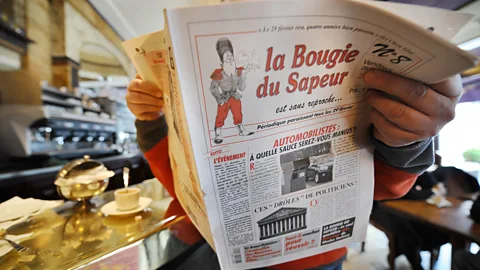

So it seems we are stuck with leap days. But this year, on this most unusual of dates why not take the opportunity to embrace the rarity. You could read along with the French by picking up a copy of the world's least frequently publish newspaper, La Bougie du Sapeur, published every leap day since 1980 (this will be the 12th edition). Or you could test your culinary skills by making pig's trotter noodles, like the people of Taiwan, who serve it to their elderly on leap day, viewing the speciality as a harbinger of good luck and longevity. Or you could just sit back and enjoy your evening with a "Leap Year" cocktail. A combination of gin, Grand Marnier, vermouth and lemon juice, its unusual combination of flavours are the perfect tonic for this unusual day. Who knows, you could even be inventive and try making up your own unique tradition to capture the spirit of the rarest day of the year.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.