How common are unexplained outbreaks of disease?

Alamy

AlamyAmid reports of a mysterious respiratory illness spreading among children in China, an expert explains how regularly unexplained outbreaks turn up.

It began one spring morning in 1993, when a Navajo family pulled into a service station in New Mexico and dialled 911. Their son, a 19-year-old marathon runner, had suddenly developed breathing problems. He was rushed to the local hospital by ambulance, where he died. The doctors were stumped – what could have killed someone so young and healthy?

It soon transpired that the marathon runner's death was not an isolated incident. He had been on the way to his fiancée's funeral, after she had succumbed to a similar respiratory illness just a few days earlier.

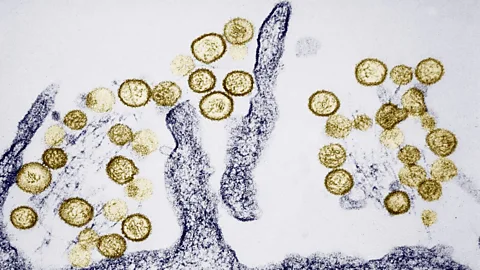

Each time reports of a mysterious new outbreak hit the headlines, there is no shortage of possible suspects. There are more viral particles on Earth than stars in the Universe, and 10 times more bacterial cells in our bodies than mammalian ones. In total, our planet is home to an estimated one trillion species of microorganisms. But only 1,513 types of bacteria, 219 viruses, 300 parasitic worms, 70 protozoa, and 200 fungi are currently known to cause disease in humans. The rest are waiting to be discovered.

What is causing the current respiratory illness in China?

On 13 November 2023, China’s National Health Commission reported a spike in the incidence of respiratory diseases, particularly in children. Then more reports began to emerge, describing swamped paediatric units, hospitals overwhelmed with sick children and clusters of undiagnosed pneumonia. Chinese officials have told the World Health Organisation (WHO) that they have not detected any new pathogens, and have instead put the outbreak down to a combination of regular winter illnesses such as RSV and the flu. Some neighbouring countries, such as India, are wary about whether this is the full picture – but the WHO is continuing to monitor the situation.

How common are mystery outbreaks?

"There are clearly some outbreaks that are still mysteries," says Stephen Morse, professor of epidemiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York.

In the case of the Navajo couple in 1993, the local medical investigator noticed that there had been other cases of this unexplained sickness in the preceding weeks. They had all occurred within the Native American community in the Four Corners region of the south-western US.

With more cases appearing each week, the race was on to catch the culprit. But it would be another two months before it was identified as hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, caused by a totally new kind of hantavirus – a group of viruses which usually infects rodents.

Delays like this are surprisingly common, even today. "There are still a number of infections that go into that general category of undiagnosed acute respiratory distress and things like that which – like the hantavirus pulmonary syndrome – aren't recognised initially but then retrospectively get teased out," says Morse.

Many outbreaks go unnoticed and unreported at first. Morse says that eventually an expert might take a particular interest in an infection, which then leads to an increase in reports. "In other places, there have been a number of outbreaks that that just don't get noticed, because the technical facilities aren't there, because they are remote areas, because there isn't motivation."

Famously, this even happened with Covid-19. In December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) was alerted to a cluster of pneumonia cases occurring in the Chinese city of Wuhan – cause unknown. The virus was officially identified within a month, when Chinese authorities shared its genome sequence with the rest of the world. However, some research suggests that the virus actually first began spreading in humans as early as October 2019.

Once an outbreak has caught someone's attention, the next step is actually finding the pathogen behind it.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow are mystery outbreaks solved?

In the case of the 1993 outbreak, the virus responsible was identified using the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), which at the time was a cutting-edge technology. Using specific sequences of DNA from known hantaviruses, scientists managed to find a previously undiscovered member of this group. "It was really the first application of molecular testing to identify the [infectious] agent," says Morse.

Today PCR is a standard method for identifying pathogens, but there is a catch. Because the technique requires a sequence from something closely related to whatever you're looking for, without even a hunch as to the possible cause of an outbreak, it's harder to get an answer. During the Four Corners outbreak, scientists already knew that those who had been infected had antibodies to other hantaviruses, so this is what they used.

However, scientists now also have access to other, more sophisticated methods for finding previously unknown pathogens – and these don't require such specific information. One recently developed method of PCR means it's possible to identify new pathogens within broader groupings. Rather than just being able to look for very close relatives of a known virus, you could find others within the same family.

Another is next-generation sequencing, which can help scientists to find microorganisms that are totally new to science. In one study of a cluster of transplant patients who had died after receiving organs from the same donor, the technique was used to discover a new arenavirus.

"In many laboratories in high-income countries or high-resource settings, you can look at the samples and identify sequences that look like pathogen sequences, whether they're viral or bacterial… without necessarily knowing in advance what's in there," says Morse.

Are the causes of some outbreaks never identified?

In 2010, an unknown haemorrhagic illness began spreading in northern Uganda. "I remember this personally, because I was the co-director of the Predict project," says Morse. There was a delay in researchers from the infection surveillance programme arriving in the area to take samples, he says. But when they did some were positive for yellow fever. "And so it was basically classified as a yellow fever outbreak, but there were negative samples from infected individuals. Presumably it was yellow fever, but we can't say with certainty," he says. Morse cites this as one of many examples of outbreaks with causes that remain an open question to this day.

So, by the time a mystery outbreak hits the headlines around the world, in most cases scientists could be well on the way to finding out what's behind it – but only in areas where they have the resources to do so.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.