The bitter dinosaur feud at the heart of palaeontology

Alamy/BBC

Alamy/BBCAs two warring bone hunters sought to destroy each other, they laid the foundations for our knowledge of dinosaurs.

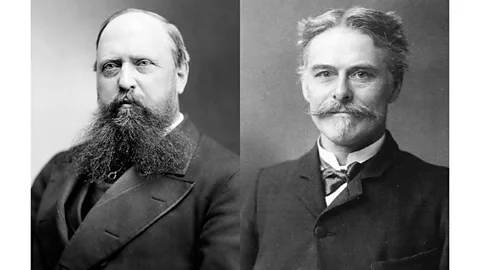

In the chilly Berlin winter of 1863, two talented American palaeontologists got talking at an otherwise unremarkable scientific meeting. The younger of the two was a tall and handsome 23-year-old named Edward Drinker Cope, who wore his thick hair slicked sideways and talked a lot. He had been sent to Europe by his genteel Philadelphian family to put an ocean between him and a young lady they deemed unsuitable.

The man he was talking to was Othniel Charles Marsh. He'd been born to a poor farming family in rural New York, but had the benefit of a very rich uncle to fund his education. At 32 years old, Marsh was reserved and a little pompous. He wore a drooping walrus moustache and his hair was beginning to thin.

Before they met, each man was enjoying the early fruits of promising careers studying fossils, geology and natural history – both were talented, ambitious and had access to family money. After their Berlin meeting, they would go on to name a roll call of the world's most iconic dinosaurs: Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Diplodocus and enormous Pterodactyls among them.

These two men were also about to embroil themselves in one of the bitterest feuds in the history of science. What began amicably in Berlin would descend throughout their lives into all-consuming jealousy, via subterfuge, spying and sabotage. Their warring troupes would brandish weapons at one another over the fossil-beds of the western US, and each man would pen lengthy character assassinations spilling over dozens of thirsty pages in the sensationalist press.

But as 1863 drew to a close in Berlin, neither of them knew anything about all that. They spent a few days together and toured the city before parting, exchanging addresses so they could keep in touch.

You might also like:

Marsh already had two degrees when they first met, and was undertaking further study at the University of Berlin courtesy of his uncle George Peabody, one of the major financiers of the 19th Century. Cope had no degrees, though he was already accruing a slew of scientific papers to his name.

Cope and Marsh had interests in common – in particular, the emerging science of palaeontology. Strange and often very large bones apparently unrelated to living species had been cropping up all over North America for many years, and science was now catching up with them to describe the prehistoric past of the continent, and the world.

Adding urgency to the study of fossils were hot debates on the new idea of evolution by natural selection. On the Origin of Species had come out a few years previously in 1859, shifting the ground beneath Europe and America's men of science (and they were mostly men, though they were standing on the shoulders of female pioneers like Mary Anning). Finding ancient bones that could substantiate the theory of evolution by natural selection was becoming a lively pursuit in the United States.

When both Cope and Marsh went back to their respective homes in Philadelphia and New Haven, they brought a melting pot of ideas from Europe back with them. That, and the acquaintance who would torment them for the rest of their lives.

American Museum of Natural History

American Museum of Natural HistoryAt first, though, the two men appeared to get on, exchanging letters, manuscripts and fossils for several years. Their early correspondence was friendly, though according to David Rains Wallace, author of The Bonehunters' Revenge, perhaps a little one-sided. Cope wrote volubly, declaring his friendship and covering every square inch of the paper with his terrible handwriting. His new friend Marsh wasn't quite so forthcoming – where Cope was "warm but impetuous", the general opinion of Marsh was "glacial and unloved".

"Marsh was taciturn," says Wallace. "He was very self-directed." He rarely shared any more than he needed to, even with close acquaintances, preferring to publish his thoughts and discoveries in scientific journals first. That way, there was little risk of others stealing his ideas.

Their differences in character didn't appear to put either off, to begin with. In early 1868, they went on an expedition together to Haddonfield, New Jersey, where marl beds – a mixture of clay, silt and other sediments – held many Cretaceous fossils. Ten years before, Cope's mentor Joseph Leidy had identified one of the first dinosaur bones in the US at Haddonfield, and mentor and student had gone on to explore the fossil beds together. With characteristic candour, the enthusiastic young Cope shared with his friend Marsh some of the area's most promising sites for fossil hunting. Cope knew the area well, and together they discovered three new dinosaurs that season.

The rich offerings of Haddonfield's fossil beds made a deeper impression on Marsh than Cope anticipated. When Cope later returned to his old haunts alone, he was no longer able to excavate fossils for himself – Marsh had paid the site managers to pledge all the bones found in the area to him alone. It was, perhaps, Marsh's first overt transgression of their friendship.

The names of the species they dedicated to each other in the years that followed reveal growing tensions. Cope made the first move, declaring a rather modest amphibian new to science to be called Ptyonius marshii in 1869. Marsh responded after a while with a "gigantic serpent" he named Mosasaurus copeanus – however, this specimen was from one of the quarries that Cope showed Marsh, notes Sarah Shelley, a postdoctoral researcher in palaeontology at the University of Edinburgh, who has studied Cope's early mammals. "In the same year, Cope described another specimen which he named Mosasaurus depressus," she says.

Things only got worse from there.

Alamy

AlamyMarsh may have been devious but Cope had his own flaws, which contributed to the greatest mistake of his career.

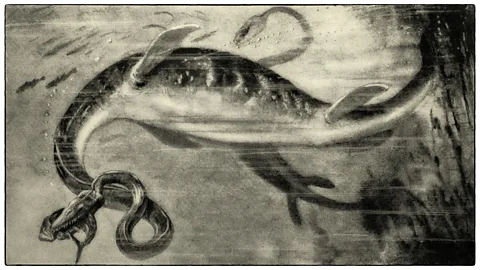

It happened when remains of a large fossil skeleton were dug up from western Kansas and sent to Cope for identification. Cope described the fossil as a species new to science, which he named Elasmosaurus platyurus. It was a marine-dwelling reptile that lived during the Cretaceous, related to plesiosaurs, measuring around 40ft (12m) from tip to tail.

"It possesses a tail of great length, which was elevated, compressed and adapted for sculling the ponderous body through the water. The limbs appear to have been disproportionately small," Cope wrote to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. The animal's head and neck, however, posed some problems. He noted that the loose rock and sediment around the fossil appeared to conceal some crucial details of the structure.

One much larger detail, however, escaped his attention. When he reconstructed the skeleton, his old associates Marsh and Leidy both came to see it; both had their reservations about Cope, but the 28-year-old was proving to be prodigious in his discovery of remarkable new species.

The reptile's head, as his colleagues saw almost immediately, was alas on the wrong end, perched at the tip of the animal's tail. As Cope first reconstructed it, E. platyurus had an extraordinarily long tail and a short neck. It should have been the other way round.

"He misidentified the neck vertebrae and tail vertebrae, and vice versa," says David Bainbridge, palaeontologist and veterinary anatomist at the University of Cambridge. "This was partly because the skull was found near what we now know to be the tail vertebrae. Bones do often get jumbled up between death and fossilisation. However, it is possible to work out 'which way round' vertebrae are."

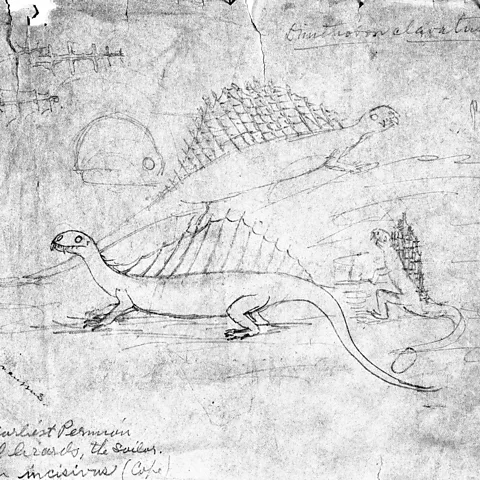

The first to point out the error in print was Leidy, who also used the opportunity to correct a comparable error of his own at the same time. Cope claimed Leidy didn't bother to tell him about the paper on his mistake before it came out in print, Wallace notes. Later on, Marsh would claim that he was the one to first point the error out to Cope – saying that Cope took it badly and became enraged. Whether or not he lost his temper, Cope clearly felt embarrassed by his mistake. In his later sketches of E. platyurus, the head had migrated to the other end.

Cope was notoriously hasty in his academic work, publishing more than 75 papers a year at his peak – many of them short and slapdash. But putting E. platyurus' head at the end of the tail was another level from his usual minor inexactitudes. As historian Jane Davidson of the University of Nevada, Reno writes, "the question was, and remains, how could Cope have made such a seemingly obvious mistake in reconstructing E. platyurus?"

Davidson argues that Leidy, Cope's mentor, would not have been likely to wait years to point out his mentee's mistake, or to do it in print first rather than in person. Leidy was a gentle and agreeable person (who sported a beard as bushy as Marsh's and hair as thick as Cope's) and he disapproved of Cope's war-like approach to palaeontology. More likely, Davidson suggests, was that Leidy spoke to Cope about the error early on, but Cope was too proud to correct his mistake. "We are dealing here with an example of Cope's well-known arrogance," Davidson writes.

Though Leidy spotted it first, Marsh would make full use of Cope's error for the rest of his career and bring it up with relish whenever he wanted to cast doubt on his rival's competence.

Alamy

AlamySoon after their joint expedition to New Jersey, Marsh moved west to have better access to even richer fossil beds in the western badlands. He was beginning to make a name for himself. His uncle had funded the new Peabody Museum at Yale and, as part of the bargain, established a position for his nephew Marsh, who would be the university's first professor of palaeontology.

He may have landed his position through family connections, but Marsh showed himself to not only be good at his chosen career, but to have an innate grasp of politics, newspapers, and how both could be bent to his advantage. On one expedition in 1868, Marsh stopped off in Syracuse to take a look at a renowned discovery that had been all over the papers. The find was the Onondaga Giant – apparently an enormous petrified man who had been dug up on a farm in Onondaga County. After a peremptory look at the giant (who was being shown at a dime a ticket), Marsh spotted the hoax – clear tool marks in the crevices of the block of gypsum from which the man had been carved. Marsh went back to catch his train. He settled down to debunk the discovery, and soon his name was in papers across the country.

Marsh was perhaps the first palaeontologist who knew how to feed and manipulate the public's fascination with ancient finds. "A lot of the media excitement for palaeontology began then, especially with Marsh," says Wallace. "Cope never was able to manipulate the press very well."

Nor did Cope's hasty publishing style allow him to establish his reputation internationally to the same degree as Marsh, who published less frequently but with more care, reserving his articles for the most prestigious journals. Cope struggled too to gain influence with funders of expeditions, so often had to pay for his work out of pocket.

What Cope lacked in political and media acumen, he made up for with his powers of imagination. He would write excited letters from his expeditions back to his wife Annie Pim Cope and, when she was older, his daughter Julia Biddle Cope. From a dig in Kansas, he told Annie of the remarkable abundance of fossils in the landscape: "If the explorer searches the bottoms of rainwashes and ravines, he will doubtless come upon the fragments of a tooth or jaw, and generally find a line of such pieces leading to an elevated position on the bank or bluff where lies the skeleton of some monster of the ancient sea."

Picturing these long-dead creatures was as much a part of Cope's work as analysing their bones. When considering giant Pterodactyls, he saw how "these strange creatures flapped their leathery wings over the waves, and, often plunging, seized many an unsuspecting fish; or, soaring at a safe distance, viewed the sports and combats of the more powerful saurian at sea. At night-fall, we may imagine them trooping to the shore, and suspending themselves to the cliffs by the claw-bearing fingers of their wing-limbs."

The awe with which Cope spoke about dinosaurs could be infectious, one of his field assistants recalled. When Cope "began to speak of the wonderful animals of the earth, those of long ago and those of today, so absorbed did he become in his subject that he talked on as if to himself, looking straight ahead and rarely turning toward me, while I listened entranced", the assistant wrote.

As Wallace argues in his book, "If any one American naturalist was the inspiration for the prehistoric images that have captured the 20th Century's imagination, it was Cope."

Peabody Museum

Peabody MuseumA decade after the Elasmosaurus incident, however, Cope and Marsh's rivalry was starting to absorb them more than the fossils they worked on. Cope had lost his friendly candour when talking to fellow palaeontologists about fossil sites, and Marsh had developed an elaborate system of codenames with his allies to refer to Cope (Jones), money (ammunition), success in fossil collecting (health) and even Pterodactyl (drag).

No sooner than Marsh would get a "notice of a new and gigantic dinosaur" to press in July 1877, describing an animal found near Golden City stretching 50-60ft (15-18m)-long and larger than any other land animal known at the time, than Cope would find a bigger one. In August, he announced a creature that "exceeds in its proportions any other land animal hitherto discovered, including the one found near Golden City". He called it Camarasaurus supremus.

"They wanted to outdo each other and name more," says Shelley. "They're rushing out quite a lot of work without really taking the time to study it. They just find a specimen and then they name it."

The duo's haste to one-up each other led to a taxonomic tangle that would take their successors years to unpick, with many species given half a dozen different names that then had to be painstakingly pruned out of use. "It's just a bit of a mess," says Shelley.

The University of Cambridge's Bainbridge says modern researchers take a much more cautious approach. In Cope and Marsh's time, after each expedition heavily laden railway trucks full of bones would haul their finds back east. "But because they were excavating so quickly, we don't have any context about where the fossils came from, or what position they were in, or anything useful like that," says Bainbridge. "One of the things that we have learned from the feud is that the speed at which you excavate fossils isn't necessarily the most important thing."

Modern palaeontologists are "not quite so obsessed with new fossils now as we used to be", Bainbridge says. "Although, of course, it is new fossils that tend to make the news."

Peabody Museum

Peabody MuseumSafe to say, both Marsh and Cope were very much obsessed with naming new species. They gathered vast quantities of fossils, many of which were extraordinary specimens that remained in sealed boxes until their deaths; owning these fossils (and ensuring their rival didn't own them) had become more important than analysing them. Worse, Cope accused Marsh of ordering his bone hunters to smash any fossils they couldn't take back with them, to prevent Marsh's rivals – and one in particular – benefitting from any they had missed. Marsh, of course, denied this.

It wasn't just physical specimens that they fought over. One ally of Cope's alleged that Marsh engaged in open intellectual theft at least once, attending a lecture on Permian reptiles by Cope and scurrying back to his office to write it up, holding back the Journal of Science until he could file the report as his own. "In science, priority of discovery is secured by first publication," Cope's ally later wrote. "It is in this manner that Professor Marsh has won his laurels as a scientist."

Marsh's extensive planning, codenames and even infiltration of Cope's field expeditions with spies could not subdue his rival. As Elizabeth Noble Shor writes in her book The Fossil Feud, Marsh was once seen in his laboratory at the Peabody bending over a specimen with a paper by Cope clutched in his hand. "Gad!" he exclaimed, looking between paper and fossil. "Gad! Gad! Goddamnit! I wish the Lord would take him!"

Meanwhile, in the bottom right-hand drawer of his desk, Cope was accumulating a stash of what he called his Marshiana. "In these papers I have a full record of Marsh's errors from the very beginning," he confided in a friend, "which at some future time I may be tempted to publish."

Cope was open about how he felt about Marsh and his allies, to the extent that he named a fossil after them collectively: Anisonchus cophater. When a friend searched Greek dictionaries to find the root of the species name, he drew a blank. "It's no use looking up the Greek derivation of cophater, because it is not classic in origin," was Cope's reply. "It is derived from the union of two English words, Cope and hater, for I have named it in honour of the number of Cope-haters that surround me."

There was a reason Cope chose that particular creature to commemorate his enemies. "It was a very ugly little specimen," says Shelley. "There is an underlying sense of humour to it."

American Museum of Natural History

American Museum of Natural HistoryOutside the realms of their squabbling, both men committed palaeontological crimes on a much larger scale. Their most active years coincided with the intense conflicts between Native Americans and European settlers. Many expeditions – Marsh's early work in particular – were undertaken alongside military escorts. Cope, with fewer government connections, usually went unaccompanied. Marsh, typically, turned to politics to establish influence, publicly supporting the Oglala Lakota leader Red Cloud (Maȟpíya Lúta). His actions may have been guided by his desire for the fossils in Red Cloud's lands, as well as the publicity that came with weighing into public debate. "He was not enthusiastic about Native American culture," says Wallace.

Besides their considerable monetary value, Adrienne Mayor describes the rich significance of the fossils among Native American tribes, who told creation stories about how these creatures turned to stone, passed down for generations.

As well as dispossessing Native American lands of vast quantities of fossils, both Cope and Marsh subscribed to popular racist ideas of the time that held the white male to be the pinnacle of evolution. In one letter, Cope eagerly described robbing a Native American grave to examine the human remains in this light. Marsh, too, would plunder graves for the same reason.

Cope and Marsh were not unusual for the time. The US, among many other countries, has a long history of fossil dispossession from indigenous lands, and while palaeontological practice today has changed in many ways, Hannah Hensel, Sandra Carlson and colleagues at the University of California, Davis, argue there is still room for improvement.

Peabody Museum

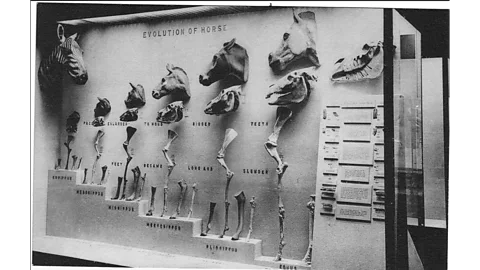

Peabody MuseumCope and Marsh's early careers were peppered with dinosaur finds, but for the majority of their lives they were more concerned with mammals – one of Marsh's most celebrated discoveries was a progression of prehistoric horse fossils showing how they evolved over time. Their other interests were in fields such as herpetology (Cope), birds with teeth that lay between birds and reptiles (Marsh), and ancient marine reptiles (both Cope and Marsh). It was only later on that they would make their most famous dinosaur discoveries, and even then they wouldn't be fully appreciated in their lifetimes.

Many of these dinosaurs came from Como Bluff in Wyoming, between the towns of Rock River and Medicine Bow. Both Cope and Marsh explored the windy ridge overlooking an expanse of sagebush prairie, a desolate place with brutal winds that ripped through the bone hunters' camps. Cope and Marsh visited their field hands by rail in a luxurious Pullman car, which came complete with plush wool carpet, richly upholstered chairs and an ornate wooden dining table. Their field assistants had to make do with starker conditions.

The dinosaurs of Como Bluff were unlike anything Cope or Marsh had ever seen, unparalleled in both quantity and quality. The dinosaurs first found here included the heavily armoured Stegosaurus and the 90ft (27m)-long Diplodocus (Marsh's finds).

Cope accused Marsh of trespass on his territory, while Marsh's men flung down dirt and rocks from the bluff at rival bone hunters until they went away.

The luxurious visits out west in Pullman cars couldn't last indefinitely. The fire of their vendetta began to burn through both men's resources – Cope's first.

Cope had always struggled to get government funding for his expeditions, and with the aid of Marsh's expert manipulation of people who mattered, he was eventually alienated from the scientific establishment. Deciding to find funds elsewhere, he invested his family money in mining. It did not go well. He threw good money after bad for some time, until he was left destitute. The two houses he had bought in Philadelphia (one for his family, the other for his fossils) were mortgaged, and without a regular income he began living month-to-month, trying to glean money from friends to repay his debts where he could.

Not content to let his ally fade into insignificance, one of Marsh's connections tried to get Cope's fossil collection confiscated, saying it didn't rightly belong to him. This plan didn't work, and in turn Cope called the provenance of Marsh's fossil collections into question. Marsh's own career began to crumble when he had to resign a prestigious position at the US Geological Survey in 1892, after criticisms of the survey's lavish spending on his work. Meanwhile, a recession was biting at the pockets of the Peabody estate, and Marsh had to mortgage his palatial house and ask Yale for a salary for the first time.

As Wallace points out, it really didn't have to end that way. If they had wanted to, they could have reconciled. They could simply have abandoned their relentless nettling of each other and found another way to pass the time. Cope's mild-mannered old mentor Leidy, for instance, who was reluctantly drawn into some of the feuding, quickly grew tired of it and withdrew from palaeontology altogether. He spent the rest of his career studying microbes.

Instead, caught in each other's webs, Cope and Marsh tied themselves in ever tighter knots as they grew older. "I think they were both tremendous egomaniacs," says Wallace. "And you know that goes along with the sort of tragic arc of the story. They were great men, but they had a lot of hubris, you know, the basic element of Greek tragedy."

The pinnacle came in 1890, towards the ends of their lives. The newspaper editor of the New York Herald was trying to compete with the New York World, which had an exclusive publishing the dispatches of Nelly Bly as she attempted to travel around the world in less than 80 days (she did it in 72). If it weren't for this newspaper rivalry, perhaps the New York Herald might not have amplified Cope and Marsh's own quite so garishly, devoting pages over the month of January to strings of allegations with headlines like "Scientists wage bitter warfare", "Long smouldering embers of hatred", and "Battle of the scientific giants still being waged".

It may not have been as exciting as Bly's expedition, but it filled columns. It also dismayed the scientific community. Some allies rushed to Marsh's defence and some to Cope's, but many followed Leidy and simply walked away shaking their heads.

American Museum of Natural History

American Museum of Natural HistoryAlthough their feud ended up discrediting both men and embarrassing their colleagues, what seems certain is that their enmity drove both ever harder to find and name more fossils, opening up the nascent field of palaeontology for generations to come.

"Before Cope and Marsh there were just a few dinosaurs known," says Shelley. "After them there were hundreds. There's an absolute wealth of knowledge in those early descriptive papers, and some of the drawings are beautiful. We still use them in our science now."

More than anything, our popular view of dinosaurs has been shaped by Cope and Marsh more than any other palaeontologists.

"When I was young and just getting interested in dinosaurs, I didn't realise at the time that the core story was largely based upon the animals that these two men or people who worked for them discovered, across Montana, Wyoming, Colorado," says Bainbridge. "They really discovered the classic species. Those species have dominated certainly children's understanding of a dinosaurs from then until probably about now.

"Everybody knows where the fossils came from, but I think the actual rivalry people know little about."

After Cope's death, one friend mused whether the vendetta was what palaeontology needed. "Perhaps there was a scientific providence in all this; perhaps such antagonistic spirits were necessary to enliven and disseminate interest in this branch of science throughout the country," his ally wrote. "This rivalry was tonic to Cope."

Perhaps Marsh felt similarly. Without the tonic of his rival's jealousy, Marsh died just two years after Cope, alone.

--