What did dinosaurs sound like?

Alamy

AlamyWe tend to associate dinosaurs with ground-shaking roars, but the latest research shows that this is probably mistaken.

You'd feel it more than hear it – a deep, visceral throb, emerging from somewhere beyond the thick foliage. Like the rumble of a foghorn, it would thrum in your ribcage and bristle the hairs on your neck. In the dense forests of the Cretaceous period, it would have been terrifying.

We have few clues for what noises dinosaurs might have made while they ruled the Earth before being killed off 66 million years ago. The remarkable stony remains uncovered by palaeontologists offer evidence of the physical prowess of these creatures, but not a great deal about how they interacted and communicated. Sound doesn't fossilise, of course.

Now with the help of new, rare fossils and advanced analysis techniques, scientists are starting to piece together some of the clues about how dinosaurs might have sounded.

Tom Williamson

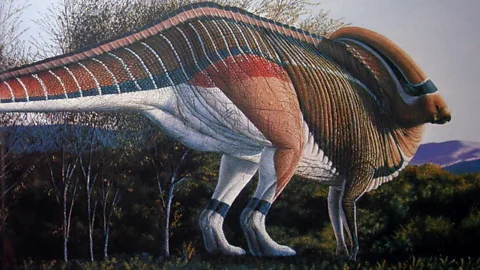

Tom WilliamsonThere is no single answer to this puzzle. Dinosaurs dominated the planet for around 179 million years and during that time, evolved into an enormous array of different shapes and sizes. Some were tiny, like the diminutive Albinykus, which weighed under a kilogram (2.2lbs) and was probably less than 2ft (60cm) long. Others were among the biggest animals to have ever lived on land, such as the titanosaur Patagotitan mayorum, which may have weighed up to 72 tonnes. They ran on two legs, or plodded on four. And along with these diverse body shapes, they would have produced an equally wide variety of noises.

Some dinosaurs had greatly elongated necks – up to 16m (52ft) long in the largest sauropods – which would have likely altered the sounds they produced (think about what happens when a trombone is extended). Others had bizarre skull structures that, much like wind instruments, could have amplified and altered the tone the animals produced. One such creature, a herbivorous hadrosaur named Parasaurolophus tubicen, would have been responsible for the fearsome calls described at the start of this article. (You can listen to the sound in the video further down this article.)

You might also like:

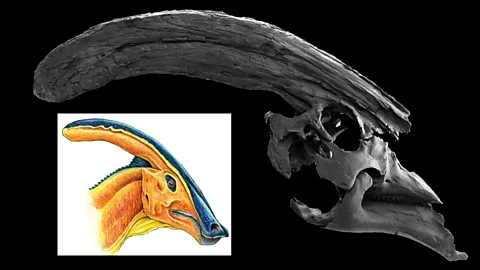

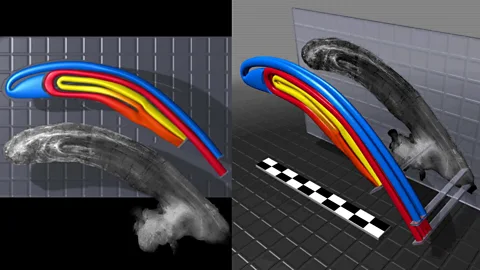

P. tubicen had an enormous crest almost 1m (3.2ft) long protruding from the back of its head. Inside this were three pairs of hollow tubes running from the nose to the top of the crest, where two of the pairs performed a U-bend to wind back down towards the base of the skull and the animal's airways. The other pair widened to form a large chamber near the top of the crest. In total they formed what was essentially a 2.9m (9.5ft) long resonating chamber.

In 1995, palaeontologists at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science unearthed a nearly complete skull of this unusual looking Parasaurolophus. Using a computerised tomography (CT) scanner, they were able to take 350 images of the crest, allowing them to see inside in unprecedented detail. Then, working with computer scientists, they digitally reconstructed the organ and simulated how it might behave if air was blown through it.

"I would describe the sound as otherworldly," says Tom Williamson, one of those who worked on the dig and is now curator of palaeontology at the museum. "It sent chills through my spine, I remember."

Roars or rumbles: the sounds of dinosaurs on film

Reproducing the sounds made by dinosaurs is a particular challenge for television and filmmakers.

While the Jurassic Park movies give their dinosaurs the kind of deafening roars that install terror into audiences, the producers behind the BBC's new series of Walking With Dinosaurs chose a different route.

"We relied a lot on a process called called 'phylogenetic bracketing'," says Jay Balamurugan, an assistant producer who worked on the series. "It is essentially the process of looking at living relatives on either side of the family tree of prehistoric animals to infer what characteristics their ancient cousins would have had. In the case of dinosaurs, we look at birds and crocodilians, and see what traits in sound those two groups share – such as hisses, bellows, and rumbles. Because they share these features, it is likely that dinosaurs did too."

* The new series of Walking With Dinosaurs starts on BBC One in the UK on 25 May in the UK and on PBS in the US on 16 June. You can find information on how to watch the series where you are in the world via the series website on BBC Earth.

The closest analogues he can find in living animals today are the vibrating grunts of the southern cassowary, which lives in Australia. This flightless bird emits a series of deep bellows and growls that reverberate through the thick jungle where they live.

"It's easy for me to imagine a misty Late Cretaceous rainforest setting with those eerie sounds thundering in the background," says Williamson. "The sounds are of low frequencies – just what is necessary to penetrate the dense undergrowth."

Williamson and his colleagues simulated the sound P. tubicen might have produced both with and without an assortment of vocal organs, such as the larynx found in mammals and modern reptiles. They found that even without a larynx or the equivalent voice box, the dinosaur may still have produced a noise due to the way air would have resonated inside the crest when the animal blew air through it, much like blowing over the opening of a jug.

"We didn't have preserved soft tissues and we don't know, for example, if these dinosaurs had sound-producing organs such as mammals and birds do," says Williamson. "It became apparent that a sound-producing organ wasn't necessary to get the crest to resonate because it is such a long structure."

Other hadrosaurs had similar, if not so dramatic, musical crests on their skulls that are thought to have doubled as a visual display and an aid to vocalisation. Most would have produced low-frequency sounds, and the fossilised remains of these animals have even inspired some to create musical instruments based on hadrosaur skulls.

Not all dinosaurs were blessed with what amounted to a trumpet atop their heads. And we have no fossilised evidence of voice boxes from dinosaurs, leading some to speculate the animals may even have been mute.

"What we do have are fossil clues that can tell us about different parameters of the airways like its diameter and its length," says Julia Clarke, a palaeontologist at the University of Texas at Austin. "We can compare those geometries to see how they relate to those dinosaurs that are living today – birds."

Tom Williamson

Tom WilliamsonBut Clarke has another clue that has provided a further piece of the puzzle. In the mid-2000s, she and her colleagues conducted a detailed examination of the preserved skeleton of an early type of bird found over a decade earlier by Argentinian researchers on Vega Island, a tiny scrap of land on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. The fossil itself remains partially embedded in a piece of rock, but using advanced CT scanning techniques, Clarke and her team were able to detect bits of the fossil hidden from view. They then digitally reconstructed the fossil from the scans.

And there, nestled amongst the fossilised bone fragments, were the remnants of something astonishing – the mineralised rings of a syrinx, the sound producing organ found in birds, dating back to the time of the dinosaurs.

The primitive bird it belonged to – a goose-like creature called Vegavis iaai – would have coexisted with non-avian dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period, 66-68 million years ago. At around this time, this part of modern Antarctica would have been covered in temperate forests and surrounded by shallow seas. The honking sounds of V. iaai were probably part of that landscape.

But for Clarke, the discovery reveals something else by its presence – that these sound-producing organs can fossilise, and their absence from most dinosaur fossils is telling. Birds, or avian dinosaurs to be more precise, evolved from theropod dinosaurs around 165-150 million years ago during the Jurassic period. If the syrinx from a bird living 66-68 million years ago could be preserved as a fossil, what has happened to the voice boxes among the remains of their extinct non-avian cousins, such as Tyrannosaurus rex?

Roger Harris/SPL/Getty Images

Roger Harris/SPL/Getty ImagesOnly one known dinosaur voice box has ever been discovered, belonging to a non-avian dinosaur known as Pinacosaurus grangeri, an armour-plated creature that roamed the land on four legs and wielded a club-like tail around 80 million years ago. The larynx, which was unearthed in modern Mongolia in 2005, may have worked in a similar way to the syrinx of modern birds. Analysis published in 2023 suggests the creature may have produced loud, explosive calls and complex bird-like vocalisations similar to those produced by parrots, using its larynx to modify the sounds.

Discoveries like these have led Clarke to delve deeper into how modern birds produce sound. "There are around 10,000 living species of birds [some estimates put the number as high as 18,000], but there has been surprisingly little scientific research done on what sounds they actually make and how they do it," she says. Her work has led her to a revelation that will shake the ground from under the feet of five-year-olds and movie goers around the world. Dinosaurs almost certainly didn't roar. They probably cooed instead.

Or more accurately they may have produced sounds in ways similar to the way doves coo or ostriches boom. Many modern birds use what is known as closed-mouth vocalisation, where sound is made by inflating the throat rather than passing air through the syrinx. Crocodiles – another distant relative of the dinosaurs that split from a common ancestor around 240 million years ago – also use closed-mouth vocalisation to generate deep rumbles that can cause the water around them to "dance" around their bodies. Crocodiles, like other reptiles and mammals, have a larynx rather than a syrinx that produces the sound. But they bypass this when producing their mating bellows.

"The Jurassic Park films have got it wrong," laughs Clarke. "A lot of the early reconstructions of dinosaurs have been influenced by what we associate with scary noises today from large mammalian predators like lions. In the Jurassic Park movies they did use some crocodilian vocalisations for the large dinosaurs, but on screen the dinosaurs have their mouths open like a lion roaring. They wouldn't have done that, especially not just before attacking or eating their prey. Predators don't do that – it would advertise to others nearby that you have got a meal, and it would warn their prey they are there."

Instead Clarke believes that many non-avian dinosaurs may have produced sounds with their mouths closed by inflating the soft tissues of their throats, as part of some sort of mating display. But she says they could also have used open-mouth calls in other situations, such as moments of distress. "There's going to be a lot of different kinds of sounds out there in the landscape of the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous," she says.

It is a view supported by research on another part of dinosaur anatomy for which there is better evidence in the fossil record – their ears. Studies of dinosaur skulls have allowed palaeontologists to reconstruct what their inner ears were like. A few fossils have also revealed some of the delicate bones that helped dinosaur ears to function.

"Dinosaurs only had this single bone in their middle ear, the stapes – a key structure in translating vibrations in air, sound waves, to the inner ear that can then be processed by the brain," says Phil Manning, professor of natural history at the University of Manchester. "Us mammals also possess the malleus (hammer) and the incus (anvil)."

Without these additional pieces of bony hearing apparatus, dinosaurs may only have been able to hear a much narrower range of frequencies compared to mammals, Manning says. And they were probably attuned to picking up low frequency sounds.

Tom Williamson

Tom Williamson"The stapes in dinosaurs were often quite large, almost the size of a matchstick in T. rex, meaning it was well tuned to lower frequencies," says Manning. "Small species of dinosaurs with smaller stapes would correlate with high-frequency sounds."

The size of the cochlear ducts in the inner ears of dinosaur fossils offer other insights about their hearing abilities, and suggest they could have also been able to pick up high frequencies. "We know from living animals that the longer the cochlea, generally the greater range of sounds it can hear," says Steve Brusatte, professor of palaeontology and evolution at the University of Edinburgh. "Mammal cochleas are coiled like a snake, to pack in a long length into a small region of skull. Dinosaur cochleas aren't like this, but some of them are pretty long."

One detailed study of a species of tyrannosaur – a horse-sized predator from the mid-Cretaceous called Timurlengia euotica, which prowled what is now the Kyzylkum Desert in modern-day Uzbekistan – has revealed that these animals had unusually long cochlear ducts in their inner ears. "That suggests that it could hear a wider range of sounds than many other dinosaurs," says Brusatte who led the study. When we studied the CT scans of Timurlengia, we noticed that its cochlea was really, really long for a dinosaur."

In fact dinosaurs might have developed these elongated cochleas fairly early on in their evolution, perhaps in the very early days of their branch of the evolutionary tree, known as the Archosauria, around 250 million years ago.

"The cochlear elongation denoting sensitivity to squeaky noises occurred near the origin of the archosaurian 'ruling reptiles', which includes birds and crocodiles," says Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, associate curator of vertebrate paleontology at Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, in New Haven, Connecticu. He has reconstructed the ear canals of several archosaurs using three-dimensional scans of their fossilised skulls. "We considered all sorts of possible drivers of this transformation and realised that the only one that was consistent with all evidence was the advent of a high level of parental care, and more specifically the use of chirping 'location calls' by the babies."

So, could young dinosaurs have been tweeting in their nests to get their parents' attention, like modern bird chicks and young crocodiles do today? Bhullar thinks they might have. "Given that baby birds and baby crocodiles chirp, it's reasonable to infer that baby non-bird dinosaurs did as well, and that their parents listened to them and cared for them just as crocodile and bird parents do," he says. "As far as what sensitivity to high-pitched sound means about the noises that adult non-bird dinosaurs made – it's an open question. I would be entirely unsurprised if most dinosaurs, and especially those closely related to birds, made a variety of noises."

Tom Williamson

Tom WilliamsonThe ability to hear a wide range of sounds could have been useful in many ways, such as detecting predators or other threats, or allowing them to scout out prey more effectively, says Brusatte. But it could have been used for communication with each other too – either to warn about danger, to attract mates, intimidate rivals or to help herds stick together.

"We know at least some tyrannosaurus travelled and maybe hunted in packs, so communication between individuals was probably important," says Brusatte.

But with such large animals producing many of these sounds, how would they have sounded to our ears? Much of the booming calls of crocodiles and cassowaries is beyond the limits of human hearing in low frequencies known as infrasound (there are even reports of alligators living close to Cape Canaveral in Florida producing infrasound calls in response to the deep rumble of the rockets during launches of the Space Shuttle in the 1980s). Elephants are also known to communicate over long distances using infrasound and Sumatran rhinos use infrasound "whistles" that resemble humpback whale song to penetrate their thick forest habitat.

Low-frequency sounds and infrasound are especially good at travelling long distances, both in open environments and dense jungle habitats. In animals the size of the T. rex or giant sauropods like the Diplodocus, the sound could have been very low indeed.

"We know there is a fundamental scaling relationship between body size and frequency," says Clarke. "Small animals produce higher frequency sounds in general because of the length of their vocal cords, unless they've got some weird modifications. Large animals produce lower frequency sounds. And so in dinosaurs, you have these animals that are the size of four elephants stacked on top of each other. They're not producing sounds in the frequency range of human hearing.

"But you would probably feel them."

Other research suggests that even if we could hear the biggest of the dinosaurs humming to one another, it would have sounded strange to our ears. Giants like the Supersaurus may not have had great control over their vocal abilities due to the relatively long delay for nerve signals to travel down the 28m (92ft) long necks from the brain. It would have meant any calls they produced may have seemed remarkably sluggish in relation to events around them.

Some paeolontologists, however, have proposed that giant sauropods like the Diplodocus and Supersaurus might have relied more upon tactile communication while moving in herds. It is perhaps the reason why they have such elongated tails, as they allowed them to stay in almost constant contact with their neighbours while they migrated.

It is evocative to imagine a Cretaceous alive with the squawks of smaller dinosaurs, chirps of newly hatched young and the menacing rumble of giants somewhere in the distance. Faced with such an assault on the ears and vibrating through your bones, it's worth considering if you would stay to take a closer look, or simply turn and run.

* This article was originally published on 14 December 2022. It was updated on 23 May 2025 to include some new research on Pinacosaurus grangeri and details of the Walking With Dinosaurs series.

--