The bones that could shape Antarctica’s fate

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 30 years’ time, the treaty that maintains harmony in Antarctica will be up for review – could archaeological discoveries there influence the continent’s future?

In 1985, a unique skull was discovered lying on Yamana Beach at Cape Shirreff in Antarctica’s South Shetland Islands. It belonged to an indigenous woman from southern Chile in her early 20s, thought to have died between 1819 and 1825. It was the oldest known human remains ever found in Antarctica.

The location of the discovered skull was unexpected. It was found at a beach camp made by sealers in the early 19th Century near remnants of her femur bone, yet female sealers were unheard of at the time. There are no surviving documents explaining how or why a young woman came to be in Antarctica during this era. Now, at nearly 200 years old, the skull is thought to align with the beginning of the first known landings on Antarctica.

Discover more from our 'Frozen Continent' series:

The Yamana Beach skull was a significant find – and not just for archaeological reasons. In 30 years’ time, bones such as these may come into play in territorial claims for this pristine wilderness. Nations are quietly – and sometimes not so quietly – preparing to stake their rights as the owners of swathes of the nearly uninhabitable land.

"Lots of people just don't understand that there's a darker side to Antarctica," says Klaus Dodds, professor of geopolitics at Royal Holloway University of London. "What we're seeing is great power politics play out in a space that a lot of people think of as just frozen wastes."

Lokal_Profil/Wikipedia/CC BY 2.5

Lokal_Profil/Wikipedia/CC BY 2.5The Antarctic Treaty System was first signed in 1959 but, in 1998 a protocol on environmental protection was added. It states that Antarctica is to be a "natural reserve, devoted to peace and science," and prohibits all activities relating to Antarctic mineral resources, except as is necessary for scientific research. But this is not set in stone forever.

In 2048 – 50 years after the protocol was created – this part of the treaty could come under review. That is the date when the prohibition on mining and resource extraction could – and it's a big could – be altered or done away with.

"The reason 2048 looms large is because if certain countries feel that the prohibition on mineral exploitation is no longer to be respected, people worry that the whole thing could unravel," says Dodds. "Environmental protection is one of the key headlines of the treaty."

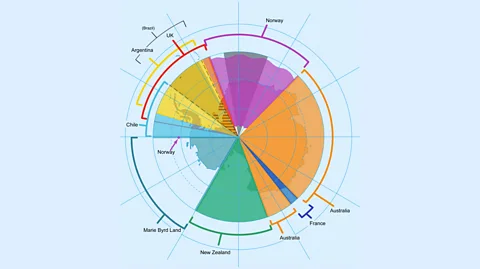

Seven nations laid overlapping claims on Antarctic land when the treaty was adopted: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK. The treaty held all these claims in place and prohibited any new ones from being established. The treaty also puts any expansions to territorial claims to Antarctica on hold – officially.

"The claimant states, in a sense, keep their claims in a box, if you like, with a lid on it. But that box will never be thrown away," says Jill Barrett, an international law consultant and visiting reader in international law at Queen Mary University of London.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany nations, however, are engaging in 'doublethink' about this part of the agreement, says Dodds. "The big players, usually China and Russia, are thinking about this particular episode around 2048 and planning ahead."

As a result, many countries are sending feelers out to Antarctica in a number of ways, such as financing scientific research, historical investigation, and building research bases far and wide around the continent. "It's a very clear message to the wider world: we're in the whole space," says Dodds.

Archaeology is one of the most important activities, says Michael Pearson, an Antarctic heritage consultant and former deputy executive director of the Australian Heritage Commission. "It establishes an interest, if not a stake, in future discussions about territorial claims or commercial exploitation."

While archaeological finds like the discovery of the Yamana Beach skull carry no legal weight – the woman was more likely to have been a sealer than an official – they might just challenge the known timeline of the continent’s history. If Chile can demonstrate that it had people living in Antarctica earlier than other nations staking land claims, then they have a stronger hand in negotiations.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesArchaeological discoveries can also boost political support for a case back home. "When remains or objects are found in the ice, I could see straight away it would inflate territorial nationalism," says Dodds. "Archaeology has always been really important for national politics."

Other events, such as historic shipwrecks, could play a similar role as the Yamana skull. In 1819, the Spanish frigate San Telmo was wrecked in the Drake Passage, which separates the tip of Chile from the Antarctic Peninsula. Archaeologists have searched the Antarctic islands for signs of whether any crew made it alive to the shore.

"Shipwreck remains were found there washed up on the South Shetlands," says Pearson. "Quite possibly some of the crew survived on the floating wreckage." If there were survivors, they would have beaten the British to be the first in Antarctica.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe upside of all this attention is that a single nation’s investment in archaeology can reveal artefacts and remains that can enlighten the whole world – discoveries that might never otherwise have been found. "The underlying nationalistic ambitions of countries, be they overtly expressed or covert motivations, can be beneficial," says Pearson. "They provide funding and logistical support to carry out archaeological research, which is otherwise very hard to get."

For the Chilean woman whose skull was found on Yamana Beach, the most likely conclusion is that she was caught up somehow in a sealing mission to Antarctica. She may have drowned or died of exposure on the shore. But her bones remain among the most significant archaeological discoveries ever made in Antarctica. And they are now part of a much bigger picture of soft power and national pride, in the context of the political long-game of laying claim to the frozen continent.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.