How we unravelled Maya secrets from the air

Grand Velas Riviera Maya/Flickr/ CC BY SA

Grand Velas Riviera Maya/Flickr/ CC BY SAInaccessible or easily missed on the ground, ancient Maya ruins are increasingly spotted with the help of satellite imagery – but the process isn’t always fool-proof.

Some of the most magnificent Maya murals ever found – dating to 100BC – were discovered deep in the jungle of San Bartolo, Guatemala back in 2001.

It was obvious that San Bartolo had more to offer – but the jungle was thick.

“It’s really dangerous walking through the jungle to find sites – it’s really humid, there are snakes,” explains Diane Davies, Honorary Research Associate at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL, who worked in the same area in the mid 2000’s.

“Honestly, you can be literally seven or eight metres away from a pyramid and in the jungle you can’t see it because [the vegetation is] so thick,” says Davies. However, through the analysis of satellite imagery, previously hidden archaeological sites can be found.

Davies recalls the assistance of Nasa scientist Thomas Sever who was later able to identify all sorts of fascinating features – including a lost Maya pyramid – from satellite images. Because many Maya buildings were constructed with limestone, the chemical composition around ruins has been altered over time – this shows up in some imagery.

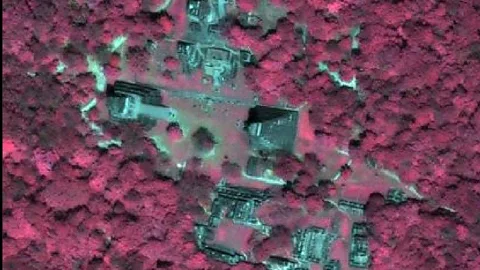

Nasa

NasaWhen scanning areas for archaeological remains, different wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum can be used to reveal patterns on the ground, says Geoffrey Braswell, at the University of California San Diego.

Light detection and ranging (Lidar), which uses lasers, may also be deployed to measure the topography.

“If you are flying over a canopy most of those beams going down get reflected off leaves and other things and don’t reach the ground – but some of them do,” says Braswell. “That allows us to see unique features on the ground.”

But Lidar is expensive and, for many years, was an inaccessible technology only used by the military. Braswell would love to use it to scan entire regions of Central America to see what sites archaeologists may have missed, but so far that just hasn’t been feasible.

There are other issues too. Most Maya scholars agree that sites detected by remote sensing should definitely be confirmed by expeditions on the ground.

This is because a lot of apparent discoveries often turn out to be nothing of interest – a field rather than the outline or a building, or something manmade much more recently than an ancient ruin.

“In the northern part of the Maya area in Yucatan [remote sensing] gives about 70% false positives,” says Braswell.

However, most agree that the benefits such technologies have made to archaeology are stunning. Some fabulous sites have been uncovered that could otherwise have gone unnoticed – and in some cases years have potentially been shaved off the effort to explore dense forest regions.

Join 600,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us onTwitter,Google+,LinkedIn and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.