The first space photographers

Snapping photos in space wasn’t always so easy. Stephen Dowling discovers how the first astronauts battled radiation and more to take stunning cosmic images.

Anyone who learned to take photographs back in the days of film will remember how frustrating it could be. Quite apart from the trickiness of loading the film, budding photographers couldn’t be sure whether they had a potential cover of National Geographic or a pile of prints fit for the litter bin until the negatives came back from the lab.

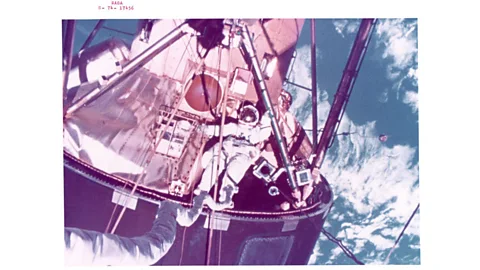

Now imagine you had to deal with these difficulties hundreds of miles above a glittering blue Earth, tethered to the space capsule that is your only link between home and the endless gulf of space. Your movements are constricted by the clumsy spacesuit that allows you to survive out here. And you can’t even hold the camera up to your face to compose your pictures properly, thanks to your ungainly helmet. Finding out whether you’ve shot a masterpiece or a mistake has to wait until you’re safely back on Earth – where you might discover that all that cosmic radiation has fogged your film completely.

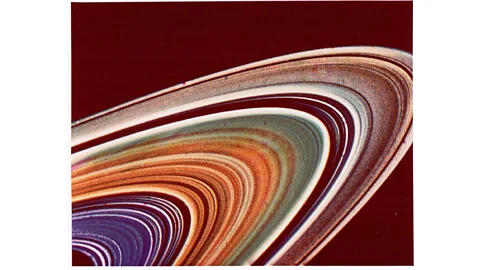

It’s a wonder Nasa’s astronauts managed to capture anything at all, let alone the astonishing images they did. A new exhibition, containing some of the most striking, opened last week in London at the Breese Little gallery. ‘Encountering the Astronomical Sublime: Vintage Nasa Photographs 1961 – 1980’ includes many images snapped by astronauts, back in those pioneering days of space exploration.

Radioactive risk

“Space missions in the 60s and 70s were definitely pushing at the limits of camera technology – and indeed the limits of every other type of technology. In many cases they didn't know how successful things would be until they actually tried it,” says Marek Kukula, the public astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich.

“It's interesting to note that when Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space in 1961 there were no cameras onboard his Vostok capsule. Just eight years later the first landing on the Moon was broadcast live on TV.”

Unlike astronauts, photographic film doesn’t need a supply of oxygen to survive. But once you’re outside the Earth’s protective atmosphere there’s a very real threat – cosmic radiation.

“Most of the really nasty stuff is blocked by a combination of our atmosphere and the Earth's magnetic field, but when you go into orbit you're giving up the protection given by the atmosphere and for missions to the Moon and beyond you're also forsaking the Earth's magnetic shield,” says Kukula. “This isn't just a problem for cameras though – you also need to protect the astronauts, so shielding is an integral part of most space missions.

“The Apollo astronauts reported seeing flashes of light on the Moon, which we now think were radiation particles passing through the fluid in their eyes – the same radiation would have been affecting their cameras too.”

All this meant that cameras needed extra shielding to protect the film within. Still, the possibility remained that an extreme radiation event, such as a solar flare, could have wiped the film – or worse, proved fatal.

Tethered cameras

There was another problem with space photography: pressing the shutter button wasn’t exactly easy, thanks to the bulky spacesuit gloves. Kukula likens it to trying to work “fiddly technology while wearing oven gloves”. Camera manufacturers like Nikon and Hasselblad had to come up with special designs so that suited space explorers could take pictures, both to aid scientific study and help to promote the space programme, which was being funded by the public purse. “Images are far greater ambassadors for public expenditure than huge swathes of raw astronomical data, a fact embraced and exploited by Nasa’s public relations department for over half a century,” the exhibition’s brochure notes.

“Cameras were adapted to take account of the practicalities of shooting in space,” says Michael Pritchard, director-general of the Royal Photographic Society. “Camera controls were extended or special alterations made so that they could be worked with heavy gloved hands. Some controls such as built in viewfinders were dispensed with as you couldn’t get the camera close to an eye for framing because of the helmet, so less accurate sights were used.

“Cameras would also make use of automatic winding of film and a number of models made use of extended lengths of film compared to standard lengths, to save the need of changing film in flight. One very practical measure was tethering the camera to the astronaut’s space suit so that it didn’t get separated if the user let go of it.”

Moon shots

The Soviets – who at the time had the biggest camera-making industry in the world outside Japan – found many of the same solutions, modifying existing designs to capture their cosmonauts in action. Earlier this year, two formerly top-secret designs – including one meant for an aborted mission to land Soviet spacemen on the Moon – were auctioned in the UK. Another design, a heavily modified Kiev medium format camera used in the Zond-7 spacecraft, sold for more than $75,000 in 2012. In appearance, they have the hallmarks of a normal camera, but with exaggerated features such as giant winding dials and protruding arms to change the lens aperture.

As some of the images in the exhibition show, our blue planet proved a dazzling backdrop, and even without the proper aids to composition, some of the astronaut photographers took impressive pictures. The image of Ed White floating in space, gold visor glinting, umbilically linked to the open door of the spacecraft would be impressive enough – the white, brown and blue of our home planet floating behind, adds an extra dimension.

The exhibition also includes images taken on the Moon, during the handful of Apollo missions that explored our nearest neighbour. Thousands of images of the lunar surface were taken on modified Hasselblad cameras, part of a family extensively redesigned for the rigours of space travel.

"The shot of the Earth rising above the moon became an emblem for the nascent environmental movement highlighting both the fragility of the Earth in space and also its uniqueness,” says Pritchard. “For this reason it’s become one of the world’s most reproduced photographs.”

But in order to save weight and allow more rock samples to be taken back to Earth, only the detachable backs of the cameras, which contained films, were kept. Almost all the cameras and lenses were left behind, destined to gather moondust until the next lunar visitors arrive…