'Swedes like generous, personal, lived-in spaces': The Scandi homeware style that Swedish people love

Courtesy of Svenskt Tenn archive

Courtesy of Svenskt Tenn archiveScandinavian interior style is not all about pared-back, minimalist living and functional, identikit furniture. Here’s why the century-old Svenskt Tenn idea of abundance, exuberance and "luxe cosiness" is still popular today.

The stereotypical image of Swedish design is of pale wood, neutral, tasteful tones and pared-down, minimalist forms. The origins of this partly lie in Sweden's espousal of functionalism (funkis in Swedish) in the early 20th Century. The Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, which attracted four million visitors, put contemporary Swedish design on the map, and soon there was a new clean-lined style of design (catchily dubbed "Scandi" by The New York Times in 1970). Meanwhile, Ikea, founded in 1943, has, over the decades, reinforced the stereotype with its stripped-down, functional, affordable furniture.

Pia Ulin

Pia UlinYet there's more to Swedish design than the Scandi cliché. An alternative approach was pioneered by influential store and manufacturer Svenskt Tenn, co-founded in 1924 in Stockholm by sculptor and silversmith Nils Fougstedt and dynamic entrepreneur and designer Estrid Ericson, and partly financed by money inherited on her father's death. The brand's 100th anniversary last year was marked by an exhibition, Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home, held at Stockholm's Liljevalchs museum. Now a newly published book, Svenkst Tenn: Interiors by Nina Stritzler, explores its story further.

Many modernist designers deemed ornament superfluous and self-indulgent but Ericson unapologetically championed the idea of bringing beauty into the home, believing it was life-enhancing. While growing up in the southern Swedish town of Hjo, she was inspired by philosopher and design theorist Ellen Key, whose 1899 book, Beauty for All, advocated economical, everyday design. "Beauty can everywhere exert its ennobling influence if only people… open their eyes and hearts to all things beautiful," she wrote in the book. "They must learn to realise that beautiful in life is not at all an extravagance; that you work better, feel better, become friendlier and more joyful if you surround yourself in your home with beautiful shapes and colours."

SVT/ TT

SVT/ TTEricson was also influenced by the 1919 book More Beautiful Everyday Things by Gregor Paulsson, who from 1917 was head of Stockholm-based organisation Svenska Slöjdföreningen (Swedish Society of Industrial Design), founded in 1845. From the late 19th Century, Sweden's traditionally agrarian society became increasingly urban and industrialised, and the society campaigned for improving standards of design in everyday life.

Svenskt Tenn, which means "Swedish pewter", initially specialised in manufacturing and selling hand-made products in pewter (relatively affordable compared to silver). Today, by contrast, the company is synonymous with its irrepressibly exuberant textiles, dreamt up by Josef Frank, an Austrian-born, Jewish designer and architect, who collaborated with Ericson until his death in 1967.

He and Ericson were on the same wavelength: crucially, they didn't share modernism's disdain for ornament. Frank took part in the landmark modernist architecture exhibition, Die Wohnung (German for "The Housing") – held in Stuttgart in 1927 by the Deutscher Werkbund, a German association of avant-garde architects and designers – and his design for a family home attracted criticism for its rooms, which were decked out with sumptuous, exuberant textiles.

Courtesy of Svenskt Tenn archive

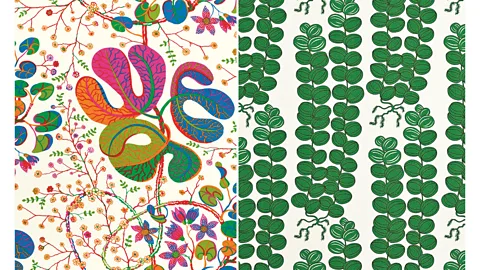

Courtesy of Svenskt Tenn archiveIn the early 1930s, Frank and his Swedish wife, Anna, moved to Sweden to escape the rise of Nazism. During World War Two, they lived in New York where Frank designed fabrics with bold, vibrant, large-scale motifs for Ericson. He described his otherworldly blooms as "not Swedish flowers but tropical fantasy flowers".

"Frank's botanical motifs were derived from books about nature that he found in New York," says Stritzler. Frank didn't speak good English and didn't adapt well to living in New York. His textiles seemed to express a desire to escape the claustrophobic, light-starved city for an outlandishly fertile, Edenic natural world. One of his most classic textiles, called Hawaii, pictures faux-naif motifs – butterflies, pendulous fruit and intertwined branches – in shades of pink, yellow and parma violet.

'Luxe yet cosy'

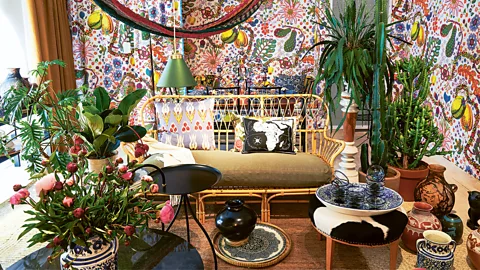

Over time, the brand offered a broad variety of products – Frank's riotously patterned fabrics and rugs, plumply upholstered sofas, lighting, rattan seating, painted wooden chairs and other homeware in a rich palette of materials, from brass to mirrored surfaces. Stylised motifs of flora and fauna stamped on textiles and trays were combined with real flowers in vases and luxuriant potted plants. Ivy climbed gracefully across the internal walls of the company's new, larger showroom in Stockholm's well-heeled Östermalm neighbourhood that opened in 1927. Svenskt Tenn, which offered an interior design service as well as homeware, soon earned a reputation for its luxe yet cosy style.

Courtesy Svenskt Tenn archive

Courtesy Svenskt Tenn archiveEricsson did much to promote Swedish design abroad, participating in such fairs as the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels (from which the name Art Deco was derived) as well as international exhibitions in the postwar years. The store was known for introducing the Swedish public to foreign designers – it mounted exhibitions on William Morris and René Lalique's glassware, and sold items by Italian artist and designer Piero Fornasetti.

Svenskt Tenn also absorbed elements of the 1930s decorative arts style Swedish Grace, a term coined by British journalist Philip Morton Shand. This fused the geometry of Art Deco with Nordic folk motifs and Neoclassical elements. Svenskt Tenn's eclecticism grew out of Ericson's love of Swedish crafts – which the shop extensively promoted – and an insatiable interest in other cultures: she travelled all over the world acquiring objects that caught her magpie eye. A pewter urn first produced by Svenskt Tenn in 1925 was inspired by an ancient Peruvian container seen at Stockholm's Museum of Ethnography.

Ericson admired Swedish artist and author Carl Larsson, who, with his wife Karin Bergöö Larsson, a textile artist, owned a cottage in Sundborn, north of Stockholm, that was depicted in many of his watercolours. The cottage (bequeathed to Karin by her father) was transformed into an idyllic home whose interiors were inspired by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement.

"It's open to the public," says Swedish-born interior designer Beata Heuman, who founded her London studio in 2013. "The couple playfully mixed strong colours and the folk motifs found further north in Sweden. The house is very layered: the pair mixed dark, ebonised wood, natural or painted wooden furniture, reclaimed wood-panelling Carl picked up from a local castle, embroidered textiles and oversized traditional Swedish stoves that look out of proportion in the spaces they're in."

Courtesy Beata Heuman

Courtesy Beata HeumanHeuman, who is also a fan of Josef Frank, adds: "I believe Ericson was influenced by Swedish folk art but was also a child of her time – of Swedish Grace and modernism – and created a new style. Frank has influenced almost all my projects. I love the patterns on his textiles that twist and turn; it's hard to see where they start and end. One is called Mirakel (Miracle) because he thought it miraculous that he'd worked out its design."

Although Ericson was passionate about preserving and promoting Swedish craft, some see Svenskt Tenn as a unique phenomenon, standing apart from Swedish design history. "The Arts and Crafts movement and Svenkst Tenn, which appeared later, share some values but I hesitate to make a straight-line trajectory between them," Striztler tells the BBC. "Ericson was a pioneer in her own right. She could create beauty from everything she touched – a simple bouquet of flowers, a table setting, which she was best known for, or a pewter object. She had a gift for creating environments that transformed rooms, making them comfortable, practical, beautiful."

According to Jane Withers, curator of the Svenskt Tenn exhibition, while the brand was influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and by Morris's textiles, a shift to its hallmark style began in the 1930s when Ericson began collaborating with Frank. "The brand's eclecticism sprang partly from Frank's aversion to the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk – the home as a complete work of art in one style. For him, being modern was about being free rather than imposing a fixed design aesthetic. Svenskt Tenn's philosophy is all about a generous, joyful, progressive idea of the home that looked beyond changing styles and dogmas to create a space of psychological and physical comfort. At a time when we're surrounded by stylised identikit interiors, this human-centric viewpoint is so refreshing."

Perhaps some of Svenskt Tenn's signature exuberance is rubbing off on Ikea: its museum in Älmhult is currently holding an exhibition called Magical Patterns, showcasing 180 boldly colourful textiles, although this is not to equate them with Frank's undoubtedly complex, highly sophisticated prints.

Courtesy Svenskt Tenn archive

Courtesy Svenskt Tenn archiveSvenskt Tenn is now owned by The Beijer Foundation, which supports research in science, medicine and design, and many of its classic designs remain popular. But the brand continues to grow, and in the recent past has collaborated with some high-profile contemporary designers.

While some see Svenskt Tenn as too individualistic to be typically Swedish, Edin Memic Kjellvertz, co-founder of Dusty Deco, a Swedish company selling contemporary and vintage furniture, believes it can't be dissociated from Sweden's culture: "Its philosophy is definitely still present and relevant. Swedes generally spend a lot of time in their homes, so they like generous, personal, lived-in spaces where handcrafted furniture, rich textiles and thoughtful details are not just there to look nice but need to feel homely. That's always been our approach."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.