'It's just a weird, weird bird': Why we got the dodo so absurdly wrong

BBC/ Karen Fawcett/ Julian Pender Hume

BBC/ Karen Fawcett/ Julian Pender HumeThe extinct flightless pigeon has captured imaginations for over 400 years. Experts and artists are now revealing how much we have distorted what the dodo was really like – nimble and slender, with a formidable beak.

When Karen Fawcett embarked on creating as accurate a model of a dodo as possible, she knew she was taking on a serious challenge.

As a palaeoartist, who creates artworks of prehistoric life based on scientific evidence, Fawcett is used to not relying on photographs to guide her work. But information on the dodo was especially scarce, she says.

"I've never seen this bird, and all I've got is some little tantalising clues about what it was like and… artist drawings and paintings of dodos," says Fawcett, who created the dodo model in her studio in Durham, UK, in 2019.

These artists often hadn't even seen a dodo themselves, she says, or were painting from taxidermy models or unhappy, captive birds in European menageries. The dodo's unusually large wings and small feet were also a challenge, she says: everything about it was "almost upside down" compared to modern birds. It all made the task all the more tantalising, though. "The dodo, it's so iconic, everybody knows what it is," she says. "I mean, there's even an emoji of a dodo on a phone. Yet nobody has seen one."

From the first encounter with dodos by Dutch sailors on the island of Mauritius in 1598 to their extinction a century later, there are plenty of depictions of this unusual ground-dwelling bird (which was, in fact, a large flightless pigeon). But disentangling truth from myth is tricky, especially when modern-day research has shown dodos were anything but the dumpy, clumsy, stupid birds so often represented.

University of Southampton

University of SouthamptonThe dodo has long been seen as an iconic image of "our ability to just destroy things", says Neil Gostling, a palaeobiologist at the University of Southampton in the UK. But today, researchers like Gostling – and the occasional artist with a scientific eye, like Fawcett – are probing the past to uncover everything they can about the real dodo, from what it really looked like and behaved, to why it evolved as it did and how it ended up among the first human-caused extinctions in modern times.

What they are discovering is firmly overturning the image of the dodo as a stupid, clumsy animal somehow destined for extinction. These scientists hope that finding out more about the dodo, and even scouring its genetics, could even help to address our current day extinction crisis.

But fascinating as it is to pursue our long-lived obsession with the dodo, can it really tell us anything about wildlife, and how to save it, today?

In unravelling the truth about the dodo, there's long been little to go on. Despite several live dodos being transported to Europe in the 17th Century, there are few remnants left anywhere today: an emaciated, mummified head known as the Oxford dodo along with a piece of skin once attached to this (these are the only surviving soft tissue); the remains of a feather; a head in Copenhagen; part of a beak in Prague; and plaster casts of a mouldy foot, itself lost sometime in the 19th Century.

Julian Hume, an artist and avian palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum in London who has published nearly 40 papers on the dodo, reckons he is the only person to have illustrated all these surviving parts of the bird. As well as these, he says, there are perhaps some 20 or 25 fossilised skeletons with some kind of skull material. But all of these, bar two near-complete skeletons from single individuals and a third partial one, are composite skeletons made from a jumble of bones from different dodos.

Apart from this, all we have are paintings from the time the dodo was alive, largely from taxidermy or captive birds. We also have a lot of inherited misbeliefs.

The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, LondonThe dodo began capturing imaginations almost as soon as it was discovered in the 16th Century. "It's just a weird, weird bird," says Gostling. "It would have stood nearly a metre tall (3.3ft)… No one would have seen anything like it in Europe, just this remarkable animal. I think people took to it."

The biggest misconception of the dodo is "that it's sort of fat, stupid and deserved to go extinct", says Gostling. "It wasn't. It was adapted to its environment, and it had been doing very well… The thing that it wasn't adapted to were rats, cats, pigs and goats, and obviously people."

And it's only really in the last decade that people have started to question the negative image of the dodo, says Gostling. "It's so pervasive." Fawcett's sculpture, he says, is the most accurate model yet made.

Before she began on it in 2019, Fawcett spent years finding out all she could about the dodo. She soon learned that many depictions were best left avoided. Among them was the famous dodo painting by Dutch artist Roelant Savery, painted in the 1620s. "I can tell you, there's lots wrong with that," she says. "It's more [like a] swan", she says: pigeons don't have "this bulbous, sticky-out bit at the front" of the neck. "And the belly on it... it's just obese, basically."

Savery is thought to have worked off a bad taxidermy bird, and apparently wildly exaggerated some features, but his depiction became the world's most well-known dodo image. It was the basis for the Alice's Adventures in Wonderland dodo illustration in 1865, which propelled the dodo to even more fame in the Victorian era. "That [idea] continued to the present day," says Gostling. "You can ask anybody, they'll know what a dodo is, and they'll draw this round bird with a funny beak and waddly feet… And it's absolutely wrong."

It didn't help, of course, that the first detailed scientific description of the dodo was only published in 1848, centuries after it went extinct. And even this was still 10 years before the theory of evolution was published, the first step to understanding how the dodo was, in fact, expertly adapted to its environment. A lot of scientists at the time took the exaggerated illustrations "as actual fact, because there was nothing else to go on", says Hume. The first reconstruction of a dodo's skeleton, for example, squeezed it into the outline of Savery's painting.

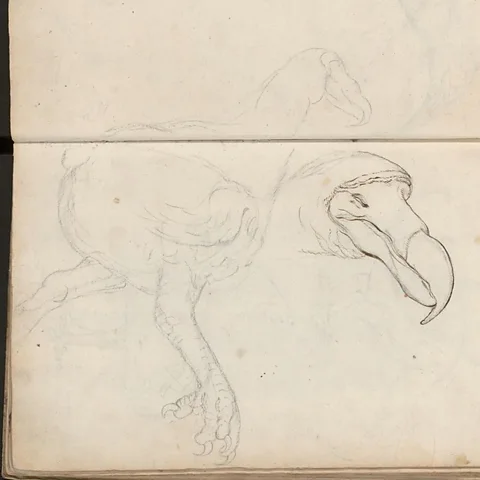

Julian Hume

Julian HumeA few apparently accurate – but less famous – contemporaneous depictions do exist, though. Some were drawn by a Dutch sailor in the first decades of the 1600s. "They are the best drawings ever of dodos, and they were the only drawings done on Mauritian soil," says Hume.

The drawings depict a more upright and slender bird than in Savery's paintings. Fawcett used these sketches to create her dodo's head, along with a replica of the mummified Oxford dodo's head and some cast skulls. Unlike some depictions, they also show a particularly hooked beak, says Fawcett (it's thought to have been a formidable weapon).

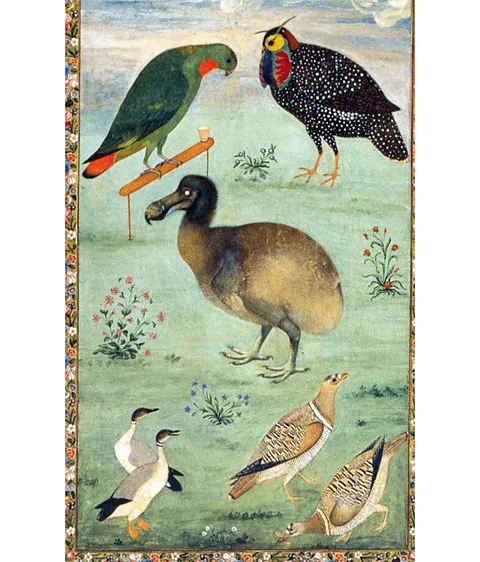

Hume, 2006

Hume, 2006Another good source was the 1625 painting by Mughal artist Ustad Mansur of a live dodo kept in a Hindustan emperor's menagerie which Fawcett used for features like colouration (it shows the dodo as having a brownish-grey colour). As the painting includes other birds still found today in the menagerie, she was able to cross-reference for accuracy.

For other details, live pigeons themselves were a handy source, adds Fawcett. "I often looked at Pidge," she says of her daughter's pet pigeon, useful in modelling finer details like how the eyelids look on a pigeon. She also used baby pigeons to model how the flightless dodo's tiny vestigial wings may have looked. Scientists now think dodos used these for balance when moving at speed.

Despite all the work to evidence her model, Fawcett acknowledges that "any form of palaeoart is a form of guesswork". It's a situation familiar to dodo researchers trying to scratch the surface of what the real dodo was like. "For probably one of the most famous birds in the world, we really don't know a lot in terms of facts," says Hume. Their ecology and population levels before humans arrived, for example, remain largely a mystery, he says. "There's so little to go on…It was such a short period of time when humans interacted with dodos."

Institute for Eastern Studies

Institute for Eastern StudiesIn a project launched last year, Hume, Gostling and a set of collaborators are now hoping to find out the truth about the dodo. To start things off, in a 2024 paper they assessed some 400 years of dodo literature, principally in an effort to classify it correctly.

The task involved disentangling centuries of folk and sailors' stories from the truth. "You've got to remember, the sailors at the time would have been recording things like mermaids," says Gostling. At some point a completely fictional "white dodo" supposedly living on nearby Reunion island was invented. "There's all sorts, dodos here, there and everywhere," says Gostling. "No there weren't. The dodo [was] on Mauritius, and it's only ever been on Mauritius."

It doesn't help that when the dodo did disappear, it was not even noticed until a century later. Even then people had trouble understanding it, says Hume. "This could not be, you know – it was God's creation," he says. Amidst the confusion it became common to believe the dodo had been a myth, he adds. "Suddenly dodos were no longer around, and people started going, well, was it a made-up bird?"

The truth of how the dodo really disappeared continues to unravel to the present day. Diaries from the Dutch sailing vessels which encountered the dodo in its home territory show it was eaten by humans, but likely seldomly, as it was considered tough and less tasty than other available game on Mauritius.

John Tenniel

John TennielIt's now believed it was animals brought by sailors that ultimately caused the dodo's demise. "The dodo laid a single egg in a nest on the ground, which made these eggs particularly vulnerable to predation by introduced species like rats and pigs, which arrived on Mauritius at the same time as people," says Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California-Santa Cruz. Rats would have also been serious competition for food, says Hume.

It's not known how many dodos lived on Mauritius before people arrived there, says Hume, but accounts from the time tell us something of how the dodo behaved in its home habitat, with one noting "they could run very fast".

Dodos, like other birds on the island, appeared relatively unafraid of people, and were easy for humans to catch when out in the open. But accounts say that the dodo was incredibly agile when it got between the rocks and the trees and would apparently "stand upright and run incredibly fast, and you couldn't catch it", says Gostling.

Modern-day research is backing this up. In 2016, Hume and colleagues used laser surface scanning technology to digitally recreate – and correct the position of – the dodo skeleton housed in the Natural History Museum in Port Louis, Mauritius' capital. "I put the bones together, worked out the angles they would have been, and it brings the dodo up into that more upright, natural shape," he says.

K F Rijsdijk

K F RijsdijkHume and Gostling also both say their ongoing (as-yet unpublished) analysis of dodo's ankle bones has shown it has large scars where apparently large tendons and ligaments were attached. “When we look at birds that have this giant tendon in their foot today… they're very fast runners, they're climbers," says Gostling. "And that's what the dodo was doing."

It all comes together to reveal that the dodo was likely much taller, slimmer, lighter and more upright than commonly thought, with relatively long, strong legs and robust limbs which allowed it to manoeuvre quickly in its dense, rocky forest habitat.

The dodo had no reason to fear humans, Shapiro notes, since it evolved on an island without predators. Much of Mauritius was extremely rocky at that time, adds Hume, and he believes that dodos had to get to the areas where the local giant tortoises, their competitors for food, couldn't. "So they evolved this ability to be manoeuvrable, get over those rocks and get to high peaks."

Gostling, Hume and their collaborators now hope to find out more about how exactly the dodo operated in its environment. "Simply working out how they moved around it is a big question," says Gostling. "We are trying to really uncover this animal. And it's a bit of a detective story."

They plan to build up the first accurate computer model of a moving dodo, recreating its musculature from the scars found on dodo bones – although funding has yet to be found for the project, says Hume.

But even while these scientists are working to find out more about the extinct dodo, a more controversial avenue is pursued to recreate it: the dodo is among the targets of "de-extinction" by gene editing company Colossal Biosciences. (Read more about why scientists are concerned about de-extinction).

The dodo's relations

The dodo's closest living relative today is the Nicobar pigeon which lives across South East Asia and looks decidedly unlike the dodo. But historically its closest relative was the Rodrigues solitaire – an even larger flightless pigeon found on the nearby island of Rodrigues, known to have used its wings as weapons. A similar confusion to the dodo surrounded the solitaire, which never made it to Europe and went extinct sometime in the 19th Century.

(Credit: Alamy)

In 2022, Shapiro, working with Colossal Biosciences, announced the sequencing of the dodo's complete genome, using a degraded DNA sample taken from a dodo skull. The results are as yet unpublished and still undergoing analysis, says Shapiro. She says the team's genetic research is "revealing the underlying DNA sequence variations that gave these birds their unique morphologies and allowing us to learn more about their evolutionary history and adaptation to their island habitats".

The longer-term plan is to use genome editing to engineer the genome of a Nicobar pigeon, the dodo's closet living relative, to "express key traits that defined a dodo", says Shapiro: its larger size, flightlessness and the unique beak suitable for consuming large fruit. The goal, she says, is both to return the dodo to Mauritius and to develop biotechnologies to stop other birds from becoming extinct. (Few tools of modern genome engineering are applicable to birds, notes Shapiro, since they cannot be "cloned" in the same way mammals can due to differences in their reproductive systems.)

Successfully creating a dodo-like bird would allow scientists to see how the dodo interacts with other species in the Mauritian habitats, says Shapiro, as well as learn more about how engineered DNA sequences manifest as differences in physical appearance and behaviour. She notes that the introduction of (non-native) giant tortoises on Mauritius (to replace the extinct Mauritian giant tortoises) has already helped to control introduced plant species and support native plants.

Hume says he'd "love to be first in the queue if they ever bring the dodo back". But he believes it is still a long way off. "I don't think I'll ever see one in my lifetime," he says. "They're looking at ways of manipulating genes and trying to get it into the parent so it actually alters [the genes] before the egg develops. It would almost be a random shot in the dark, will this one come out with a big beak, this one comes out with small wings. And then you start cross breeding, it would never be a dodo, it'd be a mix match."

Gostling also has doubts. "What Colossal is trying to do is take dodo genes and put them into the Nicobar pigeon and make a more dodo-like Nicobar pigeon. I don't know that that's really going to work."

Still, says Hume, understanding the genetics of the dodo can be used "as a basis to understand a lot". "There's a lot of research to be done, and it's all quite exciting stuff." And learning how to tweak genes to increase genetic variability could indeed help other birds, he says. The pink pigeon, for example – the last surviving pigeon on Mauritius – is in dire need of help due to inbreeding, he says: tweaking its genes for more variability could help avoid it being wiped out.

Karen Fawcett

Karen FawcettPerhaps the dodo's most lasting impact on humans is as the emblem of an extinction crisis that continues to accelerate today. What's sad, is that, unlike in the 17th Century, "we know now that we can wipe out species", says Gostling. "We know what the message is…we know what we need to do. We now need to do it."

At this moment, notes Hume, another relative of the dodo, the tooth-billed pigeon on Samoa, is on the verge of extinction. "It's going to become like the dodo, there's so few left it's probably had it as a species, which is a tragedy," he says. Many birds around the world are "on the very edge of hanging on", Hume adds. According to one recent paper, assuming no change in the trajectory of human behaviour, more than 500 bird species could go extinct in the next century.

Back in Fawcett's studio, after cutting a Styrofoam dodo body, altered replicas of the mouldy dodo foot, small wings and a carefully constructed head, she made a resin cast of the whole contraption to produce her final model. The best part, she says, was putting the eyes in. "When you put eyes in something, it gives it life."

* Jocelyn Timperley is a senior journalist for BBC Future. Find her on Twitter @jloistf

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.