'It didn't express the real horror': The true story of The Great Escape

Alamy

AlamyOn 24 March 1944, 76 allied officers broke out of a German prisoner-of-war camp, Stalag Luft III – a mission that was memorialised in a classic film, The Great Escape. In 1977, a key member of the escape team, Ley Kenyon, was interviewed on the BBC's Nationwide.

On a snowy moonless night in 1944, more than 200 allied officers attempted to break out of a German prisoner-of-war camp. It was the culmination of an incredibly ambitious plan that entailed more than a year of bribes, tunnelling, and the assembly-line production of equipment, uniforms and documents, all of which had to be painstakingly hidden from the camp's guards and spies.

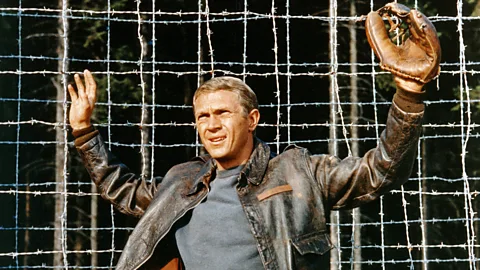

The Great Escape, John Sturges's 1963 film about the breakout, is a much-loved classic starring Steve McQueen, Richard Attenborough and James Garner. But it contains many inaccuracies. Jem Duducu, historian and presenter of the Condensed History podcast, described it in an interview in Metro as "a strange mixture of fastidious creation and pure Hollywood fantasy".

The story was first told by Paul Brickhill, one of the people who helped with the escape attempt, in his 1950 book, The Great Escape. He describes Ley Kenyon, who illustrated the book, as the mission's "star counterfeiter". Discussing the film with Dilys Morgan on the BBC's Nationwide in 1977, Kenyon said: "It was good entertainment, but it certainly didn't express the real horror of being a prisoner of war, the horror being, of course, in one's personal feelings about being behind barbed wire – the boredom, the hunger. The hunger was pretty grim."

Other ex-prisoners had a different view of the film. Charles Clarke, who was in the camp at the time, and had aided the plot as a look-out, told the BBC in a 2019 radio interview: "Even after all these years, I've always thought what a remarkable film it was."

One major change that the film made was to the personnel involved. While the events of The Great Escape are mostly rooted in fact, names were changed, and various people were combined into composite characters. At the time of the escape, no Americans remained in the compound, and the man who was said to be the model for McQueen's Virgil Hilts, William Ash, did not take part. The plan was spearheaded by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell – who in the film was renamed Bartlett, and played by Attenborough. First captured in 1940 after being shot down, Bushell had an impressive record of escape attempts, once getting within 100 yards of neutral Switzerland.

Stalag Luft III was the Germans' attempt at an escape-proof camp, specifically for air force officers from the UK, Canada, Australia, Poland and other allied countries. It was built and run by the Luftwaffe as a secure place to hold people they believed were escape risks. What they had not done, however, was consider the ramifications of trapping so many escape experts in one place.

Months of preparation

The camp was built over sandy soil that was difficult to tunnel through. This subsoil was also lighter and more yellow than the dark topsoil, making it obvious if any appeared on the ground of the camp. Huts were perched on brick legs to make tunnels down from them obvious. Brickhill describes in his book a "double barbed wire fence nine-feet (2.75m) high", just outside of which were 15-ft (4.5m) high "goon-boxes" every 100 yards or so, manned by sentries with searchlights and machine-guns. Additionally, microphones were buried in the ground around the wire so that they could pick up the sounds of any tunnelling.

As you might expect from a plan hatched by soldiers, the tunnel-digging enterprise was run with military efficiency. Bushell – also known as "Big X" – was in charge, and delegated certain parts of the organisation to other men. The planning began even before Stalag Luft III was built: Bushell and others knew it was coming, and volunteered to help build it. As a result, they were able to map it out and pick the best spots for a tunnel. Bushell had the idea that they would dig not one tunnel but three simultaneously. The logic was that if the Germans found one of them, they would never suspect that there were two others. They were to be referred to only by their codenames of Tom, Dick and Harry. Bushell threatened to court-martial anyone who even uttered the word "tunnel".

Alamy

AlamyThe aim was for 200 men to escape. This was a colossal undertaking. Each man needed a set of civilian clothes, forged passes, a compass, food, and more. Some passes needed photographs, so a camera was smuggled in by a guard who had been bribed. In the film, Donald Pleasence's character is in charge of the forgery. In reality, Kenyon was one of the forgers who had to counterfeit the thousands of pieces of paperwork necessary. In the Nationwide interview, he recalled how they made it happen: "We made a printing press, for one thing, and each letter had to be hand-carved out of rubber which we got from the cobbler – rubber heels – or bits of wood cut with razor blades." Every document had to be perfect. They replicated passes and paperwork that they had either stolen from the guards or persuaded the guards to show them. "Something like 7 or 8,000 pieces of paper were produced," he said.

The tunnels themselves were also miracles of engineering and ingenuity. An air pump was made with kit-bags and wood, and air was pumped through a line made of empty milk tins that had been sent by the Red Cross. A major issue was the dispersal of the soil that had been dug up, so bags that hung inside trousers were fashioned from long underwear and used to drop the sand around the camp, where it could be kicked into the ground.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Of the three tunnels, Tom was discovered by the guards only a short while before it would have been completed. After a break, the decision was made to continue only with Harry. This tunnel was finished in the winter of 1943, and sealed up until conditions were suitable for a breakout. That time finally came on the night of 24 March 1944. Many things went wrong, but ultimately, of the 220 people chosen, 76 made it out before the 77th was spotted by a guard.

A massive operation was mobilised to recapture the 76. They all knew that it was likely that they would be caught, but many viewed it as their duty to attempt escape. Another goal of the men was to make the Germans pull resources from their war effort to guard and search for them. According to Brickhill, five million Germans were involved in the search for the escaped prisoners. All but three of the 76 were recaptured. Two managed to make it to Sweden, and one to Spain.

Hitler wanted all 73 of the recaptured prisoners to be shot. Those around him managed to talk him out of it – after all, the British held German prisoners of war, and would not take kindly to the massacre of their officers. Still, Hitler declared that 50 of them should die. Ken Rees, who was in the tunnel when it was discovered, recounted hearing that those murdered were "taken out in twos and threes, and shot", in a BBC Witness History podcast in 2010.

Brought to justice

In the fictionalised version, all of the men are driven to a field and shot by a machine-gun, but the reality involved more deceitful measures. Brickhill's book notes that the men were taken in small groups in the direction of the original camp and shot on the way. He wrote, "The shootings will be explained by the fact that the recaptured officers were shot while trying to escape, or because they offered resistance, so that nothing can be proved later." All of the bodies were cremated, and, as Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden pointed out in a parliamentary speech given in June 1944, the only reason for this would have been to hide the manner of death.

Bushell was one of the men caught and murdered. He died aged 33. Details of his death came out in the investigation afterwards: along with his escape partner, he was shot in the back by Gestapo officers. His ashes were returned to the camp with the rest of the dead, but, according to his niece, the casket was broken when armies advanced on the camp, and so, more than 80 years later, he remains there.

Two of the men who managed to avoid execution were Jimmy James and Sydney Dowse. In a 2012 documentary, Dowse gave his perspective as a survivor. "You rather wonder why the hell you yourself weren't shot. That's what Jimmy and I felt, anyway. Why we weren't shot. We could have been. It was just luck. And… pretty terrible."

The execution of 50 prisoners of war caused outrage in the UK. Eden said in his speech to Parliament: "His Majesty's Government must, therefore, record their solemn protest against these cold-blooded acts of butchery. They will never cease in their efforts to collect the evidence to identify all those responsible. They are firmly resolved that these foul criminals shall be tracked down to the last man wherever they may take refuge. When the war is over they will be brought to exemplary justice." After the war, a huge effort was put into investigating the killings. As a result, the details emerged, and 13 Gestapo officers were hanged for their part in the executions.

It was only six years after the escape, in 1950, that Brickhill published his account of it, which was subsequently adapted into the famous film. When Charles Clarke was asked about his opinion of the Hollywood version of events, he said, "Without the film, who would remember what a magnificent achievement it was?"

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.