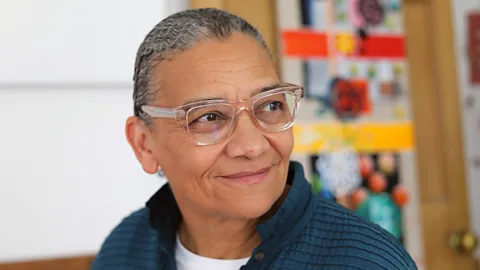

Lubaina Himid: The artist who skewers white privilege

Private collection/ Lubaina Himid

Private collection/ Lubaina HimidThe painter's satirical work has always blazed a trail – reclaiming cultural histories and identities. Precious Adesina talks to the artist – and explores an extraordinary career.

Painter Lubaina Himid says her work is not about making something pretty. "I don't expect you to attend a show of mine and go: 'It's very beautiful'. That's not what it is," she tells BBC Culture over a video call. Instead, her paintings are designed to make people think about their relationship to history, and what gets left out of textbooks.

More like this:

Himid is among the most influential black British artists alive today, and has been creating art for more than four decades. "Himid's work has encouraged many to take risks – to re-think the places we inhabit, and incite the changes we want to see," says Amrita Dhallu, co-curator of Himid's retrospective at the Tate Modern, which opens this week. "She invites us to consider the kinds of spaces that inspire our creativity, and the materials we need to imagine and make freely. Works in the exhibition, which include paintings on canvas, furniture and textiles, are brought to life with sound and poetry."

Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush Gardens

Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush GardensHimid was born in Zanzibar in 1954, and moved to England before her first birthday. As an adult, she studied theatre design at Wimbledon College of Art, and obtained a masters degree in cultural history at the Royal College of Art. But despite her studies, her art has predominantly taken a different turn. "I became more interested in drumming up real life [than making sets for plays]," she says.

In 2010, she was appointed MBE for her services to black women's art; in 2017, she won the Turner Prize; and, in 2018, she was made a CBE. Her emotive artworks have also been purchased by high-profile people, including Italian art collector Valeria Napoleone, who has Her Prints on Me (2017) hanging in her home, as seen in W Magazine. Curator Zoé Whitley and artist Joy Labinjo have both cited her as a source of inspiration. "A key lesson I learned is one that Himid taught me early on: Listen to artists," Whitley told Artsy.

"In the beginning, I was trying to fill in some of those gaps in history, and talk about individuals who had made cultural contributions in Europe," Himid says of her early work, noting that she also looked at stories about Europe's economy. The artist is soft spoken and measured in her responses, her hair scraped back in her signature loose bun. "I made a series of paintings around a French ship called the Rodeur, which sailed with captured Africans from west Africa to the Caribbean."

Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush Gardens

Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush GardensOn the ship, an untreatable eye disease spread rapidly through the enslaved people and the crew, and the "cargo" was drowned so that the traders could claim insurance. "Rather than paint hundreds of people in great distress and dying, I wanted to create something that conveyed a sense of absolute inability to understand what was happening."

Himid's painting Le Rodeur: Exchange (2016) depicts a group of well-dressed black individuals gathered in a contemporary architectural space. One figure has the head of a bird, while another holds a small piece of patterned fabric. The Tate exhibition's co-curator Michael Wellen writes in the catalogue: "[The bird-like woman] rests her hand on the shoulder of a seated man, who seems lost in thought – yet her presence is not necessarily reassuring or protective. Her alert yellow eyes look at us.".

Wellen also points out that the tailored jacket of one of the other characters caused him discomfort. "On her jacket, a small eye – like a button – stares outwards," he writes. "The detail of the eye on the woman's jacket makes me want to back away, but it's too late, I'm already in the scene, sensing the tension between the figures and wondering about my own relation to them."

The big picture

Himid considers her oeuvre activist art. "There's something that I'm trying to provoke you into being part of changing," she says. She was one of the founding artists of the UK's Black Arts Movement in the 1980s. Also known as BLK Art Group, the collective were all of African-Caribbean descent. They exhibited conceptual art across the country that critiqued the lack of diversity in the art world and commented on the social politics of the time they lived in. Class, race and gender played an integral part in Himid's work both then and today.

Nottingham Contemporary/ Andy Keate/ Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush Gardens

Nottingham Contemporary/ Andy Keate/ Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush GardensHimid often uses 18th-and-19th-Century caricature as a tool to get her message across. Her paintings reference satirists such as William Hogarth and Thomas Rowlandson who regularly featured people of colour as a way to exemplify the wealth of the white Britons in their paintings. "I want to make work that you don't feel anxious getting close to," she says, explaining that her work doesn't require an exhaustive amount of knowledge to understand. Instead, she uses different techniques to spark a conversation. "I use colour, I use text, I use pattern, I use humour – the kind of vicious British humour found in caricatures."

One of the pivotal pieces of work Himid produced in the 1980s was the installation A Fashionable Marriage (1984-6), titled after Hogarth's Marriage A-la-Mode: 4, The Toilette, (1743). Hogarth's painting mocked the cultural practices of the 18th-Century elite. Similarly, Himid's Marriage, which features 11 life-size cutouts, remarks on racism and sexism in the art world and also the relationship between the UK and the US at the time. In Himid's work, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan take the place of the lovers in Hogarth's original painting and the two black figures, almost insignificant in the 18th-Century artwork, have become key characters in Himid's piece.

Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush Gardens/ Photo Stuart Whipps

Courtesy the artist/ Hollybush Gardens/ Photo Stuart WhippsBut, it was her painted cut-outs made two decades later that won her the Turner Prize, making her the oldest person – and first black woman – to win the award. The installation Naming the Money (2004) showcased 100 life-sized cut-out figures. The people represent enslaved Africans in the royal courts of 18th-Century Europe. Himid gives each cut-out a name, identity and profession, such as drummer, dancer or map maker.

Additionally, an accompanying soundtrack gives voices to the figures, who speak of their identities before and after being forcibly taken to Europe. Through this work, Himid offers a history that highlights the creative contributions of people of colour in society at the time, beyond their role as servants.

Magda Stawarska-Beavan

Magda Stawarska-BeavanWorking with the cut-outs allows Himid to draw on different parts of her artistic knowledge. "It brings together all those things that I know about audience and drama," she says. The cut-outs are often placed in a manner that exposes the raw wooden back of the painted characters to spectators. "I'm very interested in you knowing how I did it, you being able to see around the back of it," Himid adds, further emphasising that her work isn't about beauty. As Dhallu puts it: "This expanded way of storytelling places the audience in the centre of the action, encouraging us to build new futures and think through new ways of moving through landscape, life and conflict."

Instead of creating art that leaves you ogling at its magnificence, what Himid highlights is that ground-breaking painting is about creating something that leaves a potent message with the viewer – and might just make the world a better and more knowledgeable place.

Lubaina Himid is at The Tate Modern from 25 November to 3 July 2022

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.