The forgotten bard who shaped pop

Alamy

AlamyJohn Dowland’s songs were massively popular in the Elizabethan era. They played into an idea of English melancholy that continues today, writes Andrea Valentino.

Stumble into any grimy club, or any taxi, or any supermarket in Britain and chances are that you’ll hear the same music: the same songs, the same chords, the same lyrics. Ed Sheeran has been top of the pile lately. His latest album has sold over a million copies in the UK alone, and the quaking sentimentality of Castle On The Hill is almost a new national anthem.

But if Sheeran’s floppy red hair and catchy love songs are obsessing modern Britain, he was hardly the first to grab the national mood. Back in the 16th Century, the composer and lutenist John Dowland was similarly popular – pressing into a vein of moping soppiness that made him famous, and has served English musicians ever since.

Alamy

AlamyFor such an influential musician, we know surprisingly little of Dowland’s own life. He was born about 1563, probably in London. He travelled widely, first working for Queen Elizabeth I, then for the Danish King Christian IV. Scandal chased after Dowland: he left Denmark after ‘unsatisfactory conduct’.

He was also rejected from the English court, probably for being a Catholic. And despite considerable fame, Dowland died in poverty, lamenting the “young professors of the lute” who “vaunt themselves to the disparagement” of old timers like him. This poignant end is dappled with mystery: even now, there are rumours that Dowland was a spy, and a traitor.

The beauty of sadness

If Dowland’s life remains enigmatic, personality explodes out of his songs. Just their titles – Burst Forth My Tears, Rest A While You Cruel Cares – are stickily evocative. His lyrics, meanwhile, still scrape against the heart of anyone who listens. “Burst forth my tears, assist my forward grief,” starts one, “and show what pain imperious love provokes.”

Alamy

AlamyElsewhere, Dowland sang that “down, down, down I fall, and arise I never shall.” The composer himself seemed to paddle happily about in all this. “His motto was semper Dowland, semper dolens. This means ‘always Dowland, always doleful’”, Pierre Huard, an early music performer and researcher, tells BBC Culture. Like Leonard Cohen or Tom Waits, in other words, John Dowland the angsty musician was sometimes indistinguishable from his music.

Dowland’s distinctive music was not just a personal affectation, though. Sixteenth-Century England was obsessed with “melancholy”, seeing it as. “fashionable”, says Olga Hernandez Roldan, a lecturer in music history at the Madrid Superior School of Singing. Ted Libbey, a music critic, agrees. “Melancholy was the sign of a superior individual,” he wrote, in an article for NPR. It was typical of someone “who was mature and capable of deep feeling.” These ideas seeped into 16th Century life. One scholar wrote a Treatise on Melancholy while Shakespeare cast Hamlet as bubbling with existential worries. Like all the best modern musicians, meanwhile, Dowland tapped into these feelings. If Ed Sheeran’s Galway Girl sates modern teenagers desperate for tipsy nostalgia, Dowland filled his songs with the passions of his time.

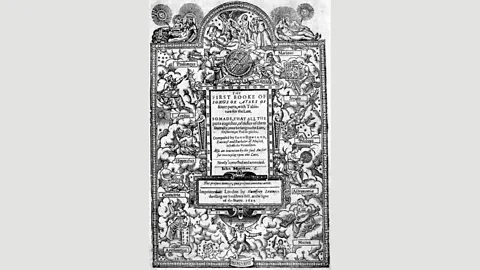

Alamy

AlamyDowland’s music was strikingly modern in other ways, too. He was one of the first composers to popularise the lute in England, spreading his music to a mass audience. Like the piano a few centuries later, it could be produced cheaply and made music accessible “to the bourgeoisie,” explains Hernandez Roldan. “The lute allowed people to play printed music at home on their own,” she adds. Dowland’s music soon became wildly popular, and one of his song books was reprinted four times during the late 1500s and early 1600s. Together with his instrument, moreover, Dowland pushed for a new kind of music. Unlike the dense Italian madrigals of the previous century, many of Dowland’s songs were “organised simply” with just an intimate solo lute as accompaniment, says Huard. “They had a big effect on the public” and helped turn English into a “European language.”

‘Shakespeare of songs’

Given all this, it’s little wonder that Dowland is now known by some as the “first modern singer-songwriter,” although not everyone agrees. “We must root Dowland in his musical context to appreciate the whole,” says Hernandez Roldan. “I feel that to speak about him just ripped out of his world makes no sense.” She has a point: scratching a line right from Dowland to modern musicians risks slipping into anachronism.

Alamy

AlamyStill, if Dowland did not wear a black leather jacket, his gushy self-expression – combined with his simple, intense style – are both hallmarks of modern pop. For Huard, Dowland is nothing short of a timeless “Shakespeare of songs” whose vivid delivery jumps down to us as strong as ever.

And if some historians might hesitate to make the comparison between Dowland and contemporary music, artists have happily adapted his passionate songs. Twentieth-Century composers like Benjamin Britten and Parry Grainger have reimagined pieces by Dowland. The Dowland Project elegantly mixes Dowland’s lute pieces with modern jazz. Dowland’s music has even stumbled back to the pop world. Elvis Costello has sung a version of Can She Excuse My Wrongs? and in 2006 Sting covered an album of Dowland’s songs, even sitting in a smoky Tudor cellar to record In Darkness Let Me Dwell.

Alamy

AlamyThe melancholic twang from John Dowland’s lute has shivered down to generations of English artists indirectly, too. In the early 20th Century, Edward Elgar’s haunting music was called ‘wonderful in its heroic melancholy’. Later, Pink Floyd released trippy songs like Time where they sang that “hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way.” Things went into overdrive as the utopianism of the hippie years quivered and died. By 1976, Joy Division were gripping worn-out kids around the country. A decade on, The Smiths went even further. Songs like Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want and How Soon Is Now? are still benchmarks of teenage worry. John Dowland may not have sung that he was “happy in the haze of a drunken hour, but heaven knows I’m miserable now” – that was Morrissey. But he could have.

Naturally, not all these musicians were influenced by Dowland directly. But starting with John Dowland and his shameless self-expression, his melancholy has proved wonderfully durable. But why do the English seem so drawn to misery? Maybe it reminds us of life’s unfairness. An old English proverb remarks that “he is a fool who is not melancholy once a day.” Or perhaps it’s the weather. As Voltaire put it, “these are the dark November days when the English hang themselves.” Whatever the reason, melancholy has surely scrabbled far enough into our national identity to stay firmly put. Hopefully, anyway. It would be a shame to lose musicians like John Dowland, whose “dainties grief shall be, and tears my poisoned wine.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.