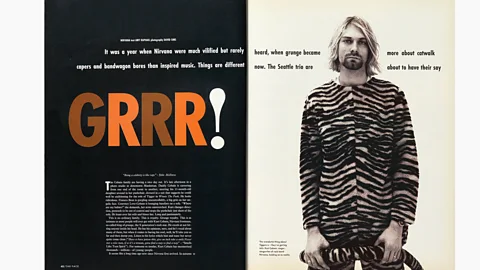

How The Face magazine captured the spirit of Gen X

The Face was the UK ‘style bible’ that encapsulated the 80s and 90s. Lindsay Baker, who worked there, looks back at the iconic magazine.

Can a magazine not only reflect culture, but even influence it and predict its trajectory? So argues the author of The Story of The Face, a new book which tells the tale of the UK music-and-style print publication of the 80s and 90s. It was known as a ‘style bible’ and an ‘almanac of cool’, and was launched on a shoestring by maverick publisher Nick Logan in May 1980. For the next two decades the forward-thinking monthly magazine blazed a trail of visual innovation and sheer energy, combining inventive photography and design with smart writing and a dry sense of humour.

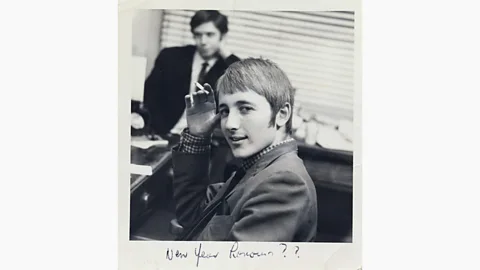

Alamy/ Nick Logan/ The Archive

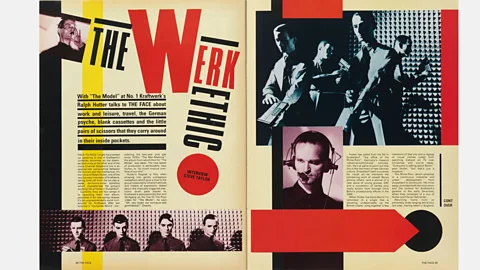

Alamy/ Nick Logan/ The ArchiveIn his book, Paul Gorman writes that the publication had a deeply influential effect on “visual culture, from broadcast media, fashion, film and graphics to interiors, as well as photography, retailing and street style.” It’s true that the magazine’s early neo-Constructivist typography and edgy graphics were copied by advertising agencies, and Levi’s used the most famous Face model at the time, Nick Kamen, for a TV ad (with an 800-per-cent jump in sales).

Although it’s hard to envisage now, in 1980 there was simply no other media besides the music press that reflected what was going on in youth culture. And of course no internet either. Because of The Face’s wide distribution, it attracted readers and contributors from all over the world, all sharing an almost tribal sense that here, finally, was a publication that ‘got them’. It helped spawn other publications, too, among them iD and Blitz, US magazine Details, and later many more.

Nick Logan/The Face Archive

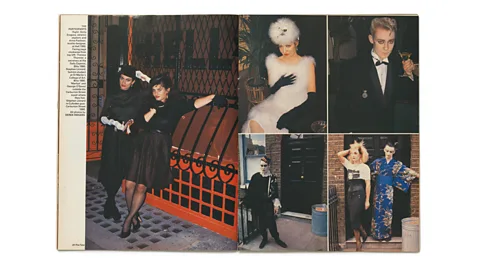

Nick Logan/The Face ArchiveThe publication introduced readers around the world to Britain’s most vibrant, street-level subcultures and most original taste-makers. Among them were the early 80s, politically-minded, multi-racial 2-Tone ska scene; the flamboyant, gender-fluid New Romantics; and the egalitarian, insurrectionary rave scene. Ideas always emerged from the ground up, which gave The Face an unusually authentic feel for the time. And despite being produced in its first decade at an analogue typesetters and on printing presses, the magazine had an unusually fast turnaround, which gave it an agility lacking in other magazines. Now in the digital era, of course that sense of rapid response and immediacy is normal.

Nick Logan/The Face Archive

Nick Logan/The Face ArchiveMany notable figures cut their teeth there – from creative directors Phil Bicker, Neville Brody and Robin Derrick to photographers such as Nick Knight, Juergen Teller and Corinne Day. There was some serious journalism in it, too, exploring social issues around Thatcherism, the implications of the Criminal Justice Bill, and the rise of neo-Nazi groups in Europe, for instance. The magazine even won an Amnesty International Media Award for a feature by Gavin Hills on child soldiers in Somalia. Big-name writers such as Julie Burchill also contributed.

Progressive vision

So what was the key to The Face’s success? “I never held a strategy meeting,” says the magazine’s founder and publisher, Nick Logan, at a panel talk organised by MagCulture. “It was about integrity. I wanted to establish something around music and then broaden it out, but I had no idea where it was going, it was open-ended. My only plan was to get the best talent, and establish trust with the writers. I believed that ‘if you build it they will come.’”

Nick Logan/The Face Archive

Nick Logan/The Face ArchiveThough run by a handful of staff and on a low budget, not long after it launched The Face was being courted by the biggest designer fashion brands in the world, all keen to be allied with the magazine’s cool aura. Former Face fashion editor Kathryn Flett recalls visiting Paris during fashion week, sleeping on a friend’s floor, and then being stunned when she was given a front-row seat at Jean-Paul Gaultier’s catwalk show, because The Face was the designer’s favourite magazine. She watched the show sitting between Catherine Deneuve and Anna Wintour. It was, she says, a “peak moment.”

Some derided the magazine as style over substance. British sociologist Dick Hebdige accused it of elitism and described it as “the embodiment of entrepreneurial Thatcherite drive,” accusing it of being “hyper-conformist… [It has] flattened everything to the glossy world of the image, and presented its style as content.” Did Logan take these criticisms to heart? “Not really, we just kept going, there was a momentum to it. I didn’t see why you couldn’t vote for a fairer world and still want a pair of Comme des Garcons trousers.”

Paul Gorman argues that in fact the magazine thrived on its “oppositional” status. He writes in The Story of The Face: “With the exception of the final two years, the existence of [Logan’s] publication – full of liberal attitudes regarding background, diversity, freedom of expression, gender, race, sexual preference, tolerance and youth – was spanned by the dominance of the Conservative Party at its most right wing.”

Thames & Hudson

Thames & HudsonLooking back, the vision presented by the magazine was certainly a progressive one. The diverse, multi-racial aesthetic of Buffalo, an informal style collective, included Ray Petri, Judy Blame and Mitzi Lorenz, models Nick and Barry Kamen, photographers Jamie Morgan and the Lebon brothers Mark and James. Buffalo played a big part in that forward-thinking sensibility, and was a dominant force in the magazine’s mid-80s golden era.

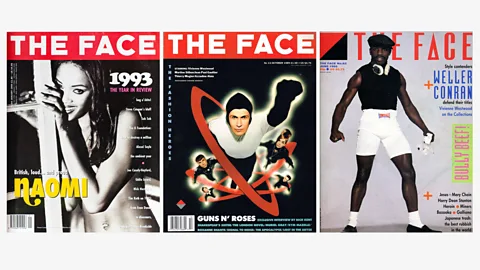

Then there were the cutting-edge, maverick musicians and other talent that the magazine championed early in their careers, from Jazzie B of Soul II Soul in 1989, described as ‘the new, funky face of Britain’, to the underground sound-system scene in Bristol that spawned Massive Attack, Tricky and the trip-hop scene. Neneh Cherry, Grace Jones, Missy Elliott, Madonna, Naomi Campbell (‘British, loud and proud’), Bjork and Courtney Love, were among the groundbreaking women artists celebrated by the magazine, many of them very early in their careers.

Young style rebels

Gorman also points out that The Face was always “inclusive”, never more so than during the late 80s and early 90s, widely viewed as the magazine’s second heyday, when the rave scene swept Britain, cutting across class, racial and regional divides with, for many, an optimistic, idealistic sense of togetherness. The editor at that time was Birmingham-born Sheryl Garrett. As Gorman puts it: “London no longer dominated. It was the music scenes in Bristol, Manchester, Liverpool and elsewhere that were important. The Face was reflecting all culture.” Nick Logan agrees: “It was never about elitism,” he says. “Magazines like [US publication] Interview were like parish magazines. I wanted to be everywhere, which is why we published 75,000. And at that time, at the start of the rave scene, I remember saying, ‘let’s aim it at those people dancing in fields.’”

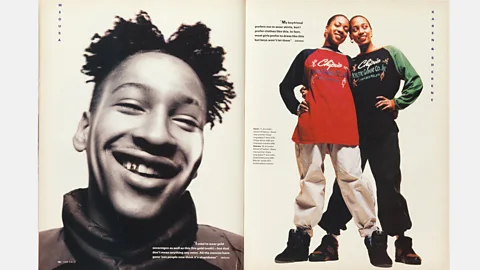

Nick Logan/The Face Archive

Nick Logan/The Face ArchivePhil Bicker, who was art director at the time, did much to propel the magazine into this second golden era, bringing a host of new photographers and stylists into the fold, many of whom went on to achieve global acclaim and commercial success, among them Juergen Teller, Venetia Scott, Corinne Day, Melanie Ward, Stephane Sednaoui, Glen Luchford, Julian Broad, Kevin Davies, Nigel Shafran, to name but a few. Stylists Karl Templer and Derrick Procope were brought in by Logan's son, Christian, who also worked there.

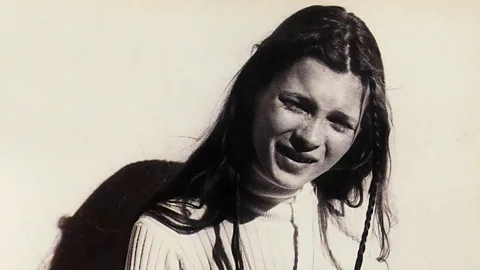

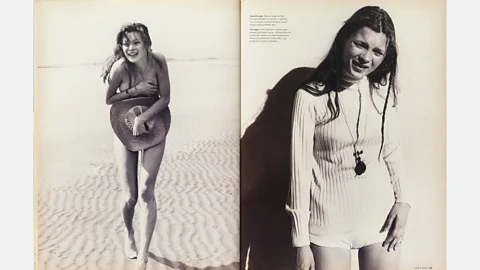

Bicker gives much of the credit to Logan for the perfectly-timed, landmark ‘Third Summer of Love’ issue. At the MagCulture talk he said: “When I showed Nick the Corinne Day photo [of a young Kate Moss in a feathered headdress, which became the cover for the iconic issue] he said ‘It’s a great photo, it sums everything up.’ Even though Kate had been on the cover a couple of months before, he said ‘yes’. Nick is a humble guy so he won’t say it, but it was him, he had the final say.”

Nick Logan/The Face Archive

Nick Logan/The Face ArchiveAt the start of the 1990s, there was an optimistic, idealistic, egalitarian sense about the decade ahead. A cover story, Young Style Rebels, featuring a slightly bedraggled Rosemary Ferguson on the cover and other unorthodox-looking models on the inside, including a waifish but defiant Kate Moss. The feature described the departure from the 80s’ glossy, glamazon model type and interviewed ‘five faces for the 90s’, all diverse and unorthodox. “After the supermodels, a new generation is coming through with new ideas and attitude,” went the intro.

‘Cultural pioneers’

The Face does feel ahead of its time – it was arguably the first ‘gender-blind’ and multi-racial magazine, aimed neither exclusively at men or women, black or white, nor at any particular sexual orientation. The new editor-in-chief of British Vogue, Edward Enninful, who came from iD magazine, cast as his first Vogue cover star Adwoa Aboah, the mixed-race model, activist and founder of digital initiative Gurls Talk. Judging by the positive response the magazine has attracted it seems that readers agree. The magazine’s new fashion director is former Face contributor Venetia Scott.

Nick Logan/The Face Archive/Alamy

Nick Logan/The Face Archive/AlamyThe intuitive, authentic, inclusive – and occasionally insurrectionary – sensibility of The Face chimes remarkably well with the current mood in publishing, online and, it could be argued, with the wider culture. Or maybe it’s just that what was the ‘counterculture’ has become more like the norm now. Either way, it’s perhaps no surprise to hear that The Face title has been acquired by a publisher, MixMag, which is planning to re-launch it online and in print next year. How does Logan feel about that? “Well, it’s not me anymore. But it might be interesting, to see the possibilities. Politically the time is fascinating, it’s fertile ground, people are thinking more deeply about politics.”

“The Face has a huge stature in the history of magazines,” says Jeremy Leslie of Mag Culture, who hosted the recent discussion with Nick Logan and Paul Gorman at London’s Central St Martin’s School of Art. “Cultural pioneers neither hold strategy meetings,” says Leslie. “Nor do they have a business plan. They do taste-making without setting out to do so. Their decisions are guided by instinct and genuine enthusiasm for what they do. This makes their businesses unique and their formula not easy to copy for competitors.”

The Face certainly reflected youth culture. You could even argue that it embodied or encapsulated a particular generation – later described by the Canadian author Douglas Coupland as ‘Generation X’. Did it change culture significantly? Well, it certainly helped nudge the counterculture along, and it has achieved an undeniably iconic status.

Nick Logan/The Face

Nick Logan/The FaceAnd although a magazine is by its nature an ephemeral thing, The Face has nevertheless remained a model that today’s independent publishers, both online and print, are echoing. There has been “a revival of interest among style-obsessed consumers of all ages in physical magazines dedicated to the latest developments in visual culture,” says Gorman. The Gentlewoman launched in 2010, and other additions to the indie-print-mag scene include Buffalo Zine, Mushpit and gal-dem, all offering a visually cutting-edge, subversive sensibility, and an intelligent encapsulation of cultural energy, just as The Face did. “There is a direct line to The Face from such titles,” says Paul Gorman. “Their touchstone is The Face. It’s still the model for moving things forward.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.