The watercolours that were warnings

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThere is much more to Francis Towne’s sketches of Rome than meets the eye: they were enchanting – and sharp – criticisms of a Britain in crisis, writes Amanda Ruggeri.

In 1780, the British artist Francis Towne left the UK to embark on the journey of a lifetime: a Grand Tour through continental Europe. He was hardly alone. Throughout the Romantic era, the trip was so popular among the English and other northern Europeans that it was seen as the pinnacle of a proper education – one that shaped Keats, Shelley, Byron and many others.

Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/Alamy

Lebrecht Music and Arts Photo Library/AlamyThese travellers, mostly men of means, wanted to go to Italy to learn: to hone their knowledge of history and their skills in sketching, painting or poetry before the great monuments of the Roman Empire. But many also took another lesson from their journeys – how the British Empire could avoid the decline of the Roman one.

Towne’s watercolours were no different. They weren’t meant to merely be pretty Romantic pictures. They were also meant as warnings to the British back home that if they allowed domestic trends to continue, London – like Rome – would fall.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British Museum“The idea that Rome offered a warning to the contemporary world was not a new one, but it had particular power at this moment,” says Richard Stephens, curator of the British Museum’s Light, Time, Legacy: Francis Towne’s Watercolours of Rome, which marks the first time that all 54 of Towne’s views of Rome have been exhibited together.

Decline and fall?

It might be hard to take such a warning very seriously today. But in certain circles, the idea that ancient Rome had collapsed because it had spiralled into moral decay – and that London might be on the same path – was a popular one.

The English historian Edward Gibbon published his first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in 1776. His thesis was that the barbarians ultimately overran the Roman Empire largely because Roman citizens themselves had lost their civic virtues. In particular, they had lost sight of the discipline, industry and toughness that once made them great.

Timewatch Images/Alamy

Timewatch Images/AlamyThis argument had special resonance in Towne’s time. After a relatively prosperous first half of the century, the 1760s had brought economic crisis and civil unrest. Social divides were intensifying. Some felt that the new king, George III, who ruled from 1760 until 1801, was riding roughshod over the civil liberties that had been re-established by William III in 1688.

For critics, the nexus of all of this was London: home of the monarchy and Parliament, aristocratic excess and commercial greed. And with overcrowding issues – the city’s population nearly doubled throughout the 1700s – those who wanted to would, indeed, have seen plenty of signs of social and civil breakdown.

Crime was so rampant that one gang even tried to rob the Prince of Wales in St James Palace itself. Travellers to London remarked that there were more prostitutes than in any other European city. Sewage ran in the Thames.

Frustrations sometimes spilled over into violence: in the infamous Gordon Riots of 1780, rioters attacked members of the House of Lords, sacked their homes, freed prisoners and set buildings on fire – an event that destroyed 10 times more property than was lost in Paris during the entire French Revolution.

Crumbling Colosseum

Some left. The city of Exeter, in particular, became home to a vibrant political and artistic circle whose members believed they carried the torch of traditional English values, including personal liberty, frugality and hard work.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumTowne was one of those artists: by the mid-1760s, he had left London for the western city. Despite routine attempts to be accepted by the London-based art establishment, bidding for election to the Royal Academy no fewer than 11 times, he was consistently rejected. The disappointment likely made him begrudge the capital all the more.

So, like many of his peers, Towne went to Italy not only to educate himself on art, architecture and history. He went to see for himself the place that had fallen into such decline – and to paint images that those back home would understand as moral lessons.

The Trustees of the British Museum

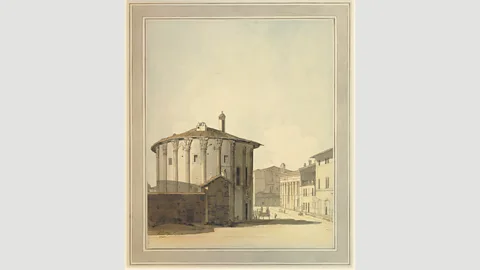

The Trustees of the British Museum“You can look at what did he paint and what didn’t he paint. He doesn’t go to Rome and paint all the great Baroque palaces and piazzas and churches, nothing at all of that,” says Stephens. “And that’s typical of the English artists of that period: they didn’t care about Catholicism and the gaudiness of the modern city. They only wanted the archaeology.”

The Trustees of the British Museum

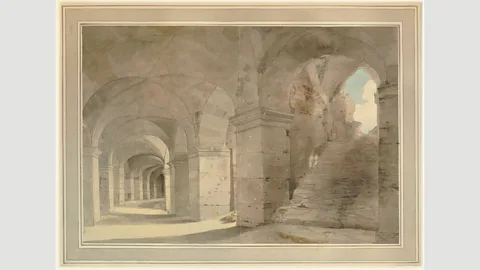

The Trustees of the British MuseumIn one painting, a gallery within the Colosseum crumbles, its floor strewn with mud, weeds poking through the masonry; in another, wild foliage climbs up the cliffs and dominates the view of the once-great Villa of Maecenas in Tivoli.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumArtists from other countries, like the Italians themselves, would paint Rome’s more recent triumphs: its Baroque fountains and opulent palaces, gold-soaked churches and sweeping piazzas.

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/AlamyNot only did Towne tend to ignore the more modern (and Catholic) monuments of Rome, but his paintings often excluded the people who populated the city. In one watercolour of the Roman Forum, he included cattle and herders. But he left the figures filled in with only a grey wash, insignificant shadows compared to the crumbling grandeur of the imperial palaces beyond.

The Trustees of the British Museum

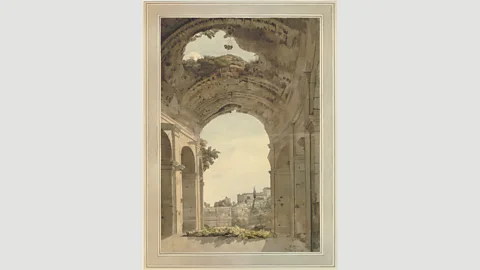

The Trustees of the British MuseumTo make the moral message even clearer, Towne also wrote on the back of his paintings. On his view from the Colosseum to the Arch of Constantine, he transcribed the arch’s wording: “through a Divine impulse with a greatness of mind, and by force of arms he delivered the Commonwealth at once from the Tyrant & all his Faction.”

“His friends at Exeter would have understood the parallel of Constantine and 1688, when William III came,” Stephens says. “It shows how he used these drawings for political purposes.”

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumAlthough none of Towne’s own writing about his work has survived, a letter to him from one of his friends underscores how he liked to present it.

“I must again express to you the Pleasure I rec’d from yr Views of Rome,” the Exeter writer and army officer Edward Drewe wrote to Towne. “If I declined entering into that historical Investigation you might have expected, it arose from my Perfect Knowledge of that History on which I founded my Military Principles and from my Delight in finding myself in Old Rome by the text & comment of yr Pencil.” Or in other words: ‘I know you were trying to tell me about what your images said about how the mighty empire fell, but spare me – I already know it all’.

As well as carrying a portfolio of his pictures to share with friends and acquaintances, Towne sold dozens of his watercolours to clients. Today, we can imagine them on the walls of Exeter homes, little reminders – and possible conversation starters – of what Britain could become.

But by bequeathing them to the British Museum 200 years ago, Towne ensured that even now – long after those conversations have fallen silent – his views would endure.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.