Why are these masterpieces at risk?

Ian G Dagnall/Alamy Stock Photo

Ian G Dagnall/Alamy Stock PhotoOver the past few decades, Britain's public art has been thrown out, bulldozed, melted down or sold off. A new campaign seeks to track down what’s missing – and protect what remains

In 2014, a school in the English town of Market Harborough sold off a sculpture from its courtyard. The children had nicknamed the piece "the broken glasses" because of its twisted shape. No one knew what it was actually called or who had made it, and the school’s administrators wanted to make room for more buildings. At auction, the sculpture fetched only £360 ($520).

Last year, the school received a call from a curator desperately trying to track down the piece. The anonymous pile of steel was in fact Astonia, a 1970s work by Bryan Kneale, one of Britain's leading sculptors. It was worth an estimated £30,000 ($43,200).

The case of the forgotten Kneale is far from unusual. Over the past few decades, Britain's public art has been thrown into skips, bulldozed over, melted down for scrap metal or sold to private collectors. Some of it, such as a 300m-tall aluminium-and-steel beacon made for the 1951 Festival of Britain, simply vanished.

Historic England

Historic England"It's part social history, part detective story. This week, something else is probably disappearing," said Sarah Gaventa, the curator of a new exhibition on post-war public art at London’s Somerset House. Gaventa was the person who called the school about Kneale’s sculpture – and her exhibition is part of a campaign to record and protect public art by the heritage organisation Historic England.

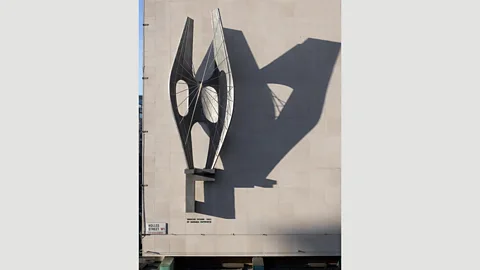

Historic England

Historic EnglandPart of the threat to Britain’s public art is that many of the pieces are outdoors. Winged Figure, a 1963 sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, graces the side of the John Lewis store on London's busy Oxford Street. Henry Moore’s Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 5 is near Kenwood House on Hampstead Heath; his Knife Edge Two Piece sits outside the Houses of Parliament. Willi Soukop's Donkey has served as a play sculpture in a housing scheme in Harlow since 1955, proving so popular that its back is now worn to a shine.

Andy Lovell/Alamy

Andy Lovell/AlamyBut even works inside buildings have been at risk.

Among the Historic England exhibition’s highlights are two architectural reliefs that were narrowly saved from destruction. A 1963 abstract relief by British artist Trevor Tennant, created for the entrance hall of a hospital in Welwyn Garden City near London, was rescued by a doctor when the building was redeveloped last year. In Cornwall, a 1984 relief by the British artist Paul Mount covered the side of a supermarket until the building’s 2009 refurbishment. A local resident rescued 60 panels – the maximum number he could fit into his garden. About 160 more ended up in a landfill site.

The contemporary artists Bob and Roberta Smith made a series of paintings in 2013 to campaign against the planned sale of Henry Moore's Draped Seated Woman, which is owned by local authorities in London’s Tower Hamlets. Nicknamed Old Flo, the sculpture was based on a woman sheltering in London's East End during the war. As a result of the backlash, it will now remain in public ownership.

Historic England

Historic England"These works become very vulnerable if we're not telling the story behind them," Smith said.

The evolution of Britain's public art is tightly intertwined with its post-war history. As the country rebuilt its destroyed cities, generous funding for the arts formed a crucial part of the political agenda. Art in parks, hospitals and social housing estates was meant to foster social values and a sense of civic pride. In some English counties, a piece of art was commissioned for every new school.

Keith Ramsden/Alamy

Keith Ramsden/AlamyEuropean artists who had fled to Britain during the war also infused the creative scene with fresh ideas. Britain became the place to be for sculptors.

"It was that moment of optimism: new schools, free healthcare, the idea that ordinary people should have the best," said Gaventa.

Public protection

But even in its post-war heyday, public art faced challenges – often from the very people for whom it was intended.

In 1972, 16 sculptures by emerging artists were loaned to different cities. Each city then had the option to buy them. The project was a disaster. A local vicar called one of the pieces "revolting" and suggested it be blown up. Except for one, all of the works were rejected.

Arnolfini Gallery

Arnolfini GalleryMore recently, soaring scrap metal prices have posed a new threat to outdoor art. In 2011, Hepworth's Two Forms (Divided Circle) was stolen from Dulwich Park in London. Police believe the 1969 sculpture was melted down for scrap. The same fate likely met a Moore bronze that was stolen in Hertfordshire in 2005: according to the police, it was melted down and sold for some £1,500 ($2,160).

As a sculpture, it was valued at £3m ($4.3m).

Diamond Geezer - Creative Commons

Diamond Geezer - Creative CommonsOne way to protect these works would be to move them inside – for example into one of Britain's free museums. Gaventa argues that this would undermine their role as everyday masterpieces.

"If you pass a work of art every day it has a much bigger impact than if you see it in a gallery," she said. "It's about our everyday journeys, about quality of life, about lifting the spirits."

Thierry Bal

Thierry BalEllen Harrison, head of campaigns at Historic England, calls public art our "forgotten national collection". The key to protecting it was not to lock it away, she says, but to make the general public feel a sense of ownership.

"If people understand what they have, then we'll all care about it more," she said.

Historic England's campaign to raise awareness includes a Twitter hunt for missing pieces as well as an attempt to catalogue all the works.

Justin Kase z12z/Alamy

Justin Kase z12z/AlamySo far, there has been no comprehensive survey on how much has disappeared. In January, the government listed 41 post-war sculptures, including pieces by Hepworth, Moore and Antony Gormley, as heritage assets – a move which grants them extra protection. An online map shows their location.

Gaventa also hopes that the drawings, models and sculptures shown at Somerset House will encourage people to go out and explore the open-air collection.

"The real stars aren't in the exhibition," she said. "They're out in the public realm."

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.