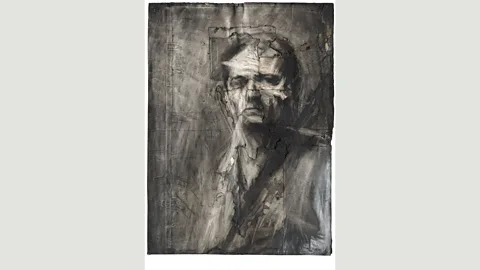

Frank Auerbach: Britain’s greatest living artist?

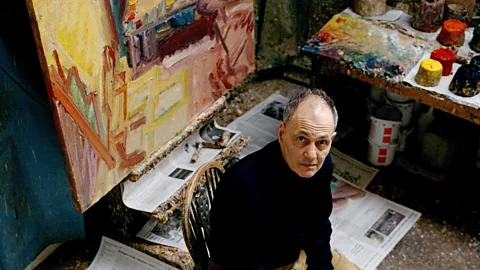

Eamonn McCabe/Getty Images

Eamonn McCabe/Getty ImagesThe celebrated 84-year-old artist Frank Auerbach paints the same subjects time and again in a tiny studio. What is it like to sit for him? Alastair Sooke goes behind the scenes.

Every Friday afternoon, as it approaches five o’clock, the art historian Catherine Lampert walks down an alleyway near a former cigarette factory in Mornington Crescent in north London, and heads towards a brick building. Her destination: a modest studio, measuring just 9m x 9m (30ft x 30ft), which the celebrated 84-year-old British painter Frank Auerbach, the subject of a new retrospective at Tate Britain, has occupied since 1954.

Lampert is one of only a handful of trusted friends invited by Auerbach to sit regularly for their portraits. Agreeing to be painted by Auerbach, it should be understood, is a daunting commitment, since it can take the artist many months, or even years, to finish a single work. A staunch perfectionist, Auerbach is rarely happy with the results of a painting session, and will often finish by scraping off all the fresh oils before beginning again, from scratch, the following week.

For nearly four decades now – since 1978 – Lampert has been visiting Auerbach on a weekly basis, almost without fail. “Sometimes I miss a Friday because I’m travelling,” she says, “but then I make up for it when I come back. You have to be there as much as you can. He’s very upset if you aren’t.”

The sitting room

Inside, the studio hasn’t changed much over the years. Though Auerbach has the wealth to transform it (his pictures sell for hundreds of thousands of pounds), he is not interested in redecorating: “There is paint peeling off the walls,” Lampert says. The only significant change that he made to the space after buying it outright was to install a “very small toilet” and a “little mezzanine bed”, where, Lampert reveals, “he spends several nights a week”.

There is a single, high window, which everybody struggles to open aside from Auerbach’s tall son, Jake, who is another regular sitter. Other faithful sitters include Auerbach’s wife, Julia, the art historian and businessman David Landau, and the art critic William Feaver.

A few postcards occupy a ledge, while on the walls reproductions of famous artworks have remained, without interference, for decades: Hogarth’s Shrimp Girl, Dürer’s portrait of Conrad Verkell, a picture by Picasso of his lover Dora Maar, “with a very jagged profile”, and a painting by Matisse of his daughter, Marguerite.

Upon her arrival, Lampert is offered a fruit juice, before the two-hour session begins. She sits wearing a T-shirt, rather than nude. During the first hour, she and Auerbach chat, but only intermittently: “I compare it to when someone is driving a car,” she says, “and you might suddenly come out with a comment, but it can relate to something you talked about last week.”

Gradually, though, the small talk recedes: “The sitters get deep into their own thoughts,” Lampert explains. “It’s nice to have that quiet, especially during the second hour. Besides, by then he’s working with such intensity that I wouldn’t want to interrupt.”

How does Auerbach approach the physical act of painting? “Abandoned,” Lampert says. “He’s moving around, scooping up paint, turning the picture upside down, looking at it in the mirror.

Sometimes he recites poetry – he could have been an actor, because he can memorise long passages very easily. Then suddenly he asks a question or makes a comment: he’s funny. Often, though, he’s just talking to himself, swearing because it’s not working. One of the reasons he has constant sitters is because he’s not at all inhibited with us. We’ve seen it all so many times – so he can shout.”

Creature of habit

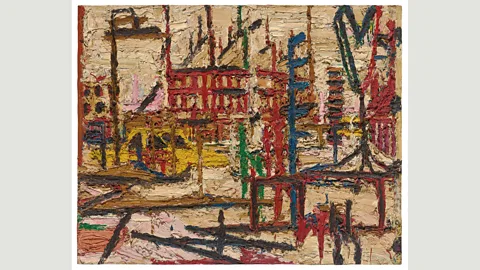

Auerbach – who was born in Berlin in 1931 but was sent, eight years later, to school in England, where he has lived ever since – is famous for his impasto portraits and landscapes depicting the environs of his studio, including buildings around Mornington Crescent Underground station, as well as vistas of Primrose Hill, a 15-minute walk away. The surfaces of his pictures are often clogged with pigment in deep, muddy layers.

Yet, Lampert says, one of the misconceptions about Auerbach is that he only applies paint thickly. “Sometimes he paints quite delicately using a small brush,” she says. “It’s not all high velocity. But it is always on his feet. I’ve never known Frank to sit down for a minute and look at the picture. It’s always active and physically arduous, and occupies practically the whole space. The time goes really quickly.”

When the session ends, Lampert lingers for 20 minutes or so, sipping an eau-de-vie brandy while Auerbach cleans his brushes and clears up the mess of splattered paint and scrunched-up newspaper. “Then we gossip,” she says.

Auerbach is notorious for adhering to an ironclad routine of painting every day, including Christmas morning: “He hates interruptions,” Lampert says. “He feels time is running out. He hardly sees any friends anymore.” He also rarely goes out: now that he’s in his eighties, even his occasional trips to the cinema and theatre have dwindled.

As a result, he relies upon those few confidantes he does see to provide him with information and diversion. Often Lampert fills him in on exhibitions opening in London, or passes on tittle-tattle about Britain’s art world. She used to be the director of the Whitechapel Gallery in east London, and they have many friends in common, including a number of the so-called ‘School of London’ painters with whom Auerbach (who shared the prestigious Golden Lion prize at the 1986 Venice Biennale) is commonly associated. Several of these artists, including the painters Michael Andrews, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, are no longer alive – but they still provide topics of conversation.

Portraits of a lady

Lampert met Auerbach in 1978 when she organised the first retrospective of his work, at the Hayward Gallery in London. “At that point,” she recalls, “he had quite a few sitters, so it might just have been a couple of drawings or whatever. But we got on really well, and I’ve always liked to have that little break in my own week, so there was no reason to stop. Frank kept saying, ‘Well, can we do another picture? Could I just do a drawing?’ But now you know it isn’t going to stop after a particular picture, unless one of us isn’t strong enough to sit or work.”

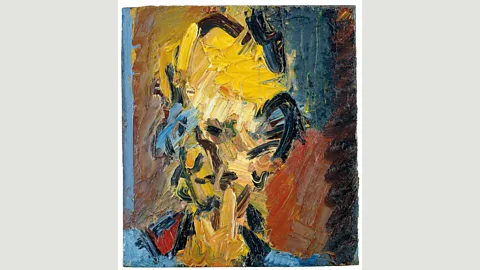

How many portraits of Lampert has Auerbach completed? “I haven’t counted,” she says. “Maybe two or at most three a year since ’78 – so more than 60, I think. I have a few – he has generously given me some. People sometimes tell me, ‘Oh, I have a picture of you!’ Or one passes through auction.” The highest price achieved at auction for one of Auerbach’s portraits of Lampert is £299,000 ($463,000).

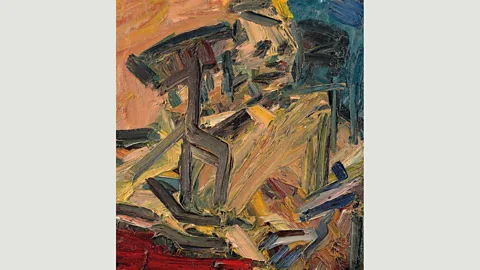

Although Auerbach is a figurative painter, his style is so gestural and intense that many of his portraits appear semi-abstract. Certainly, they could never be called conventional likenesses: they seem as emblematic of the artist’s emotional and psychological state as they do of that of the sitter. Does Lampert feel that Auerbach’s portraits of her capture anything of her personality?

“Sometimes,” she says. “One or two, I know what happened that day, what I was thinking and what was going on in my life, and he certainly has captured a lot of that. And people who know me well see my gestures.” She pauses. “But, you know, 37 years: you see yourself getting older, as life passes by. It’s great to share that as time goes on. I really think Frank’s painting is very good: resonant, gorgeous – and tough. The way he puts things is so direct. So it’s a very special friendship. I feel so lucky.”

Alastair Sooke is Art Critic of The Daily Telegraph

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and Twitter.