The young Koreans pushing back on a culture of endurance

Innovative projects are allowing Korean millennials to escape social and workplace norms that leave them always struggling to succeed. But is it only for the rich?

Kim Ri-Oh was working as a photojournalist at a magazine in Seoul when the mental stress of being the most junior employee brought her to a breaking point. Working weekends and overtime shifts that didn’t end until after 11pm was the norm. Around her two-year anniversary at the company, Kim found out that she was being paid considerably less than a male colleague who was new to the company.

“I started losing sight of what used to bring me joy. Death was on my mind often. I had done everything asked of me. Graduated from high school, college, and found a stable job that my family approved of. But what meaning did it have for me? It was my life, but I couldn’t find me in it.”

And she’s not alone. Young Koreans, many experiencing similar disillusionment, are pushing back against conventional ideas about professional success and social responsibilities. And a number of projects and businesses are springing up to support this.

Read more like this:

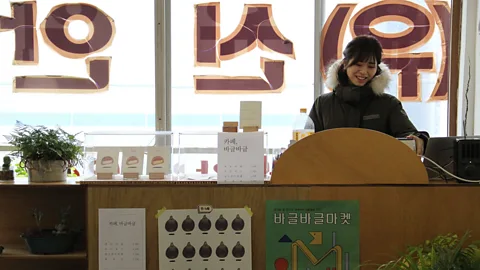

Kim, 26, now works at one such project called Don’t Worry Village. Situated in the rapidly depopulating port city of Mokpo in southwestern Korea, Don’t Worry Village was set up in 2018, with help from government funding to redevelop unused buildings, and is currently operated by a group of 20 and 30-something-year-olds. Its slogan is: “It’s okay to rest. It’s okay to fail.”

Grace Moon

Grace MoonThe village is made up of once-empty units scattered in corners of Mokpo repurposed into spaces where young creatives are running restaurants and cafes, showcasing artwork and producing documentaries.

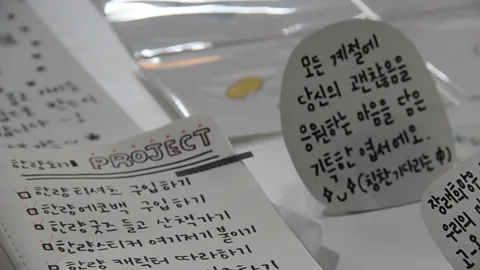

During a six-week retreat, young South Koreans, exhausted by the efforts of job-hunting, come together to embrace their previous failures and experiment creating their own projects. Some feel it’s their second chance at life. The agenda is guided by residents’ personal goals but is loosely structured around: recovering a lost sense of community, communal eating and rest time.

Park Myung-Ho, 33, who co-founded the project with Hong Dong-Woo, 34, says the village aspires to embody what is known as “sohwakhaeng”, a Murakami-inspired idea that encapsulates small but certain moments of happiness.

“Rather than obsessing over big milestones, younger Koreans are searching for sohwakhaeng,” said Park. “Whether that be indulging in a slice of cheesecake at your local bakery, writing a song or a book. Something that is small but wholly yours.”

Grace Moon

Grace MoonSouth Korea has been experiencing a population paradox in recent years, with a rapidly ageing demographic in contrast with the lowest fertility rate in the world and plummeting marriage rates. Buried underneath the glamour of the country’s K-pop and K-beauty industries, which has cultivated millions of ardent fans across the globe, lies a bleaker reality: soaring youth unemployment rates and the most demanding work hours among any developed nation.

Korean millennials refer to themselves as part of the Sampo generation, a neologism that translates to the “three sacrifice generation” – one where young Koreans must relinquish relationships, marriages and children to survive the cut-throat economy. The list quickly expanded to include four, five, seven and eventually “n”, or numerous sacrifices, like social life, home ownership.

“Young people who see themselves as part of this ‘N-Po generation’ are skeptical,” said Kim Ri-Oh. They are looking for a way to gain satisfaction from their lives outside of traditional measures of success.”

Yoon Duk-Hwan, who co-authored 2019 Korean Trends, explains that Korea has traditionally revolved around a “gathering culture”. Annual class reunions, or Dongchang-hweh, are a common example where the personal lives of classmates – from engagements and marriages to who has and hasn’t secured a job yet – become social currency.

“These gatherings reinforce an authoritarian culture that an increasing number of younger South Koreans are choosing not to partake in anymore,” Yoon says. “They’re realising that it’s possible to have a social life unattached to these circles. One that isn’t dictated by a pre-written script.”

And projects like Don’t Worry Village and a number of so-called “salons” are part of a growing number of spaces in which to do just that.

Let’s talk

Go Ji-Hyun opened Korea’s first “salon” Chwihyangwan in 2018 after being intrigued by a scene in the popular film, Midnight in Paris. The interior resembles an old-fashioned hotel. The floor and walls are a warm shade of mahogany and upon entering, visitors are greeted by the concierge.

An homage to 18th Century Parisian salons – intimate spaces where people gathered to have an intellectual exchange – Go’s salon sought to challenge the anti-discourse culture of Korea.

“Korea has lacked a culture of conversing with one another in fear of being intrusive – especially with strangers,” says Go. “When I first opened the salon, the most frequently asked question I received from visitors was, ‘How do I talk to a stranger?’”

New conversation topics are introduced every three months and are discussed in intimate settings like Socratic seminars, reading nights, scrapbook-making sessions, film viewings and bar talks. Go describes it as a social-thinking platform where members freely exchange ideas.

Grace Moon

Grace MoonAt Chwihyangwan, people don’t, and are actually encouraged not to, list their age on registration forms – an unusual instruction given how shamelessly prying Korean job application processes are known to be. During salon meetings, members refer to each other using affable nicknames and don’t reveal their real name or occupation. Go says participants range from curious college students to those in their 50s.

“Typically, Korean society pre-determines how you should act and interact with others based on these labels,” Go says. “Rather than labels, our introduction to each other is our way of thinking. Rarely can you meet people in such a way in Korea.”

Money talks

Spaces like this are seeking to democratise social relations in South Korea, where most group dynamics have been beholden to a strict script that dictates when younger Koreans must achieve certain life goals.

In the last year, the number of these types of establishments has grown in South Korea. In reality though, these spaces are inaccessible to many young Koreans, especially those who come from lower socioeconomic households and arguably, those who may need it most.

Chihyangwang

Chihyangwang“People who don’t have financial stability or live outside of Seoul experience barriers,” Kim Ri-Oh says. “Annual membership fees [to salons] are hard to pay when you’re juggling rent. Commuting to the city to go to these gatherings requires paying for a round trip on the bullet train which can cost almost $100.”

A one-year membership to Chwihyangwan costs 1,200,000 Korean won ($1,033 or £786). Whereas at Don’t Worry Village, residents pay a 500,000-won fee ($430 or £327), although the programme was initially free of charge.

Of course, the sheer idea of taking a break, or not working and having any flow of income, may not be an option for these individuals, especially when youth unemployment is swelling.

Depression is at an all-time high among Korea’s youth. According to the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, the number of people in their 20s diagnosed with depression has nearly doubled in the last five years. Communities like those found at salons can be seen as spaces for those who are lonely, says Ha Ji-Hyun, a psychiatrist and professor at Konkuk University’s Medical Centre in Seoul.

Ha says that depression has a disparate impact on low-income youth. It requires spending money on commuting, a meal or a movie ticket, for example. In other words, socialising becomes inherently tied to money and can be more of a burden than a pleasure.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, with roughly 82% of South Korea’s youth using social media, a growing number of Korean millennials who come from low-income families are starting to replace real-life interactions with digital ones.

“At a certain point, they realise that they don’t have to expend money or energy on socialising,” Ha says. “But the satisfaction they obtain from interacting with other users online has a limit… many end up experiencing a heightened feeling of depression after an elongated period of being physically isolated.”

Loneliness stems from a desire to meet and interact with people, he says. Individuals who have the financial means and energy to actively seek out spaces like salons and Don’t Worry Village can combat that loneliness, unlike those who lack the means of doing so – and may fall deeper into depression and social isolation.

Suffering in silence

Korean millennials are turning the tables and changing the power dynamics of the workplace and social settings. And while society must acknowledge that regional and socioeconomic disparities bleed deep in the country, there is an undeniable shift in how young Koreans are advocating for themselves.

Grace Moon

Grace MoonIn the case of Kim Ri-Oh, it was the exposure of a gender pay gap at work that was the catalyst to make her see the bigger picture. “It was an overlooked fact that men at the publication earned on average 200,000 won ($173 or £130) per month more than their female coworkers,” she says. “No one said anything though, and it seemed impossible for me to change things, so I left. I realised I didn’t have to suffer like this anymore.”

South Korea’s government has taken notice of this grim reality. In 2018, the National Assembly passed legislation that would drastically cut maximum weekly working hours from 68 to 52 in hopes of improving living standards.

But change also appears to be happening organically. The resignation rate after working for one year at a company reached its peak at 28% in 2018, a shift that challenged Korea’s traditional idea of the “lifetime workplace”.

In any case, young Koreans understand that suffering is no longer a prerequisite for success. Instead of simply enduring, they are becoming the authors of their own story.