The origins of Silicon Valley’s office playgrounds

Alamy

AlamyThe office playgrounds at today's tech giants have some surprising origins writes Richard Donkin

The relaxed, colourful work environments of Silicon Valley have come to define the creative atmosphere of the internet age.

Casual dress, flexible working hours and quirky job titles at internet giants such as Google and Facebook suggest a laid-back work culture. But that belies a high intensity work environment where pressure for improvement is often self-imposed.

These companies focus on empowering employees to bring their best efforts and thinking to work, free from bureaucracy and heavy-handed management. But where did this informal culture obsessed with technological innovation originate?

Many of the leaders of today’s biggest technology firms will say the answer lies in their humble beginnings. Apple, Amazon, Hewlett-Packard and Microsoft can all trace their genesis to suburban garages, often in the homes of one of their founders.

Alamy

AlamySuch origin stories – tales of young inventors working around the clock to grow their businesses and change the world – are baked into the culture of these tech giants.

But step back in time by another century or so, to America’s great age of industrial invention, and you’ll find another tech hub with striking cultural similarities to the internet giants of today.

Wave of invention

In the mid-19th century, a revolution in electronic communications set the foundation for a wave of invention on the East Coast of the United States, sparked by the invention of electrical telegraphy during the 1830s by Samuel Morse and others.

Alamy

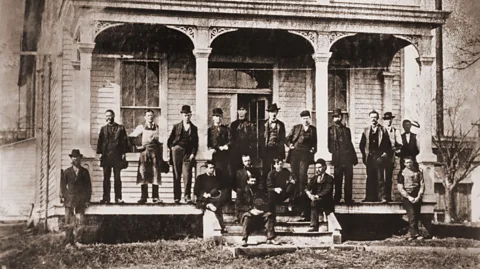

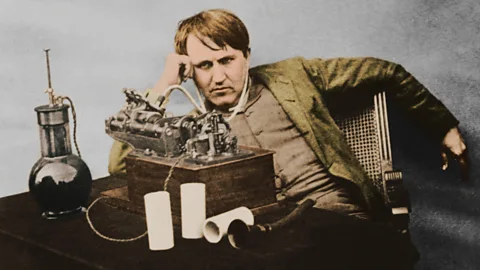

AlamyThis new form of long-distance communication quickly became essential technology, and skilled operators, so-called “Knights of the Key” were highly prized by employers. Working alone or in pairs, they developed an independent mindset and a deep understanding of the technology. The most successful of these itinerant artisans was Thomas Alva Edison.

At the age of 12, Edison began to print and sell newspapers to train passengers, working out of the baggage cars. He learned code from railway telegraphers and set up his own telegraph system at home. At 19 he joined the Western Union as a telegrapher but worked separately in his spare time on telegraph-related projects.

Alamy

AlamyThis led to his first inventions, an electronic vote-recording machine that failed to find a market, and a stock ticker that sold for $40,000, around $700,000 today. The sum was enough to establish his first workshop in an old factory in Newark, New Jersey, and a nucleus of assistants to build a research business.

‘The Wizard of Menlo Park’

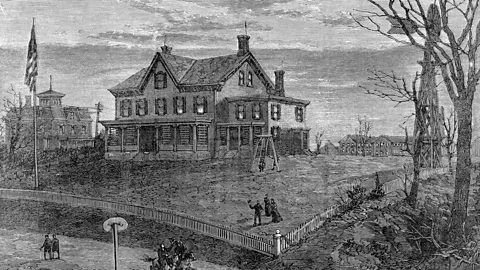

As the business grew – mostly selling systems to telegraph companies – it needed more space. So, in 1876 it moved to a purpose-built laboratory with machine-shop, library, carpentry shop and glass-blowing house on a 34-acre site in Menlo Park, New Jersey.

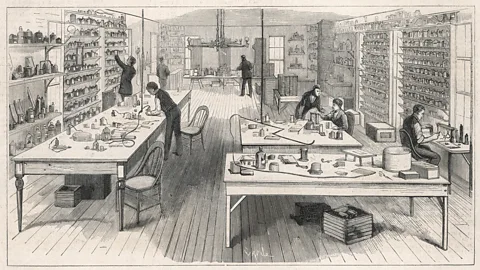

Edison tended to hire high-calibre assistants, often fresh from university, who were drawn to his infectious enthusiasm for experimentation and research.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThey didn’t earn high wages. Edison insisted that they came, not for money, but for “the chance for their ambition to work.”

Many of these assistants went on to forge successful careers in industries such as film and radio that adopted Edison’s innovations.

His researchers worked late into the night, punctuated by weekend drinking and sing-along sessions beside an organ positioned at one end of the laboratory. It was an informal, free-thinking atmosphere and Edison saw himself as one of the boys who he referred to as “muckers”. “Hell, there ain’t no rules in here, we’re trying to accomplish something,” he said.

The campus-like atmosphere of today’s internet pioneers share many features with Edison’s work regime, which mixed long hours and an exhaustive application of trial and error.

Just as long working hours can impinge on family life today, Menlo Park’s intensive work schedules proved corrosive to the domestic lives of Edison and his employees.

But the work produced results. Over 58 years, from 1868 to 1926, Edison and his team filed some 1,600 patents. More than a thousand of these were successful, ranging from the light bulb to the phonograph. More than 400 patents were filed at Menlo Park, including his most important such as that for the microphone, the improved light-bulb filament and the induction coil that improved the telephone.

Edison was a cult figure to his assistants. Others since, such as Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, have exercised unusual levels of influence over their work teams. But none of the employees of today’s business leaders sacrificed their lives in pursuit of their research, as Clarence Dally did, working for Edison. Dally literally gave his right arm for his employer. His limb had to be amputated due to radiation damage resulting from X-ray experiments. Dally succumbed to cancer and the experiments were abandoned by Edison as too dangerous.

Edison could be the fiercest of taskmasters. He “could wither one with his biting sarcasm or ridicule one into extinction,” said one collaborator. Yet, he was idolised by his workers. Electrical engineer Arthur Kennelly said, “The privilege which I had being with this great man for six years was the greatest inspiration of my life.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne of Edison’s greatest attributes was his ability to communicate the potential of his inventions to investors through publicity stunts in the media. On New Year’s Eve in 1879 he ran 40 of his new light bulbs off a dynamo that attracted thousands of visitors. The exhibition drew in backers to fund an electricity distribution station. At the time, power distribution was as important to electric lighting as the world wide web was to the internet.

In 1887, 11 years after setting up Menlo Park, Edison moved to a much larger campus in West Orange, New Jersey. He continued to experiment at home late in life, but spent less time at the laboratory in old age. He died in 1931.

Cultural blueprint

The culture established by Edison’s laboratory directly influenced the next generation of American innovators – companies such as Dupont, Westinghouse, General Electric, General Motors and Bell Laboratories, the former research arm of AT&T (now Nokia Bell Labs) all had flourishing research operations in the early twentieth century and learned both from the methodological approach of Edison and his rejection of military-style chains of command and reporting formalities.

What would have today’s internet companies made of Claude Shannon, a Bell employee who bounced along its corridors on a pogo stick when he wasn’t using his unicycle? While a fan of odd forms of transport, Shannon was also a genius. His 1948 paper, A Mathematical Theory of Communications, laid down much of the theory behind the revolution in information technology.

His fellow scientists at Bell Laboratories produced 16 Nobel Prizes over half a century – in part because they were given free reign to pursue their own research, which led to early developments in computer hardware that would underpin the foundations of Silicon Valley itself.

Little wonder, then, that companies such as 3M and Google provide scope for employees to work on their own projects. This so-called ’20 per cent time’ has led to innovations such as Gmail at Google and The Post It note at 3M.

The culture of curiosity behind today’s internet and software pioneers runs as an unbroken thread from Silicon Valley, through the research engines of many of the world’s great corporations right back to the Menlo Park Laboratory and the ideas that sparked the modern lightbulb.

That metaphor for invention, rooted in work, has enlightened the world.

Richard Donkin is the author of The History of Work and The Future of Work, both published by Palgrave Macmillan.

To comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Capital, please head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.