The flawless biscuit that took years to master

Karen Cox

Karen CoxAcclaimed musician Rhiannon Giddens spent years perfecting a flawless recipe for the iconic Southern food. Now, a new festival reveals the similar journeys of Black music and cuisine.

"Womp, womp, womp." That's the sound, according to Grammy Award- and Pulitzer Prize-winning musician Rhiannon Giddens, of a sharp-rimmed glass cutting into just-right biscuit dough. Coming from Giddens' mouth, the timbre translates as a low note plucked from a double bass.

Giddens is an American scholar-musician whose folk, country and blues music illuminates the African lineage of the banjo and celebrates the legacy of the Black string band. But in 2020, at the outset of pandemic lockdowns, Giddens found herself craving something seemingly less academic: biscuits. Not the crisp British variety that Americans call "cookies" and "crackers". Not crumbly, sweetened scones – those she could buy in abundance in her adopted city of Limerick, Ireland. No, what Giddens wanted were flaky, buttery biscuits with a definitive rise, the kind that are ubiquitous across the American South.

Five years later, after tweaking her formula and method, Giddens has landed on what she believes is a near-perfect biscuit recipe. Her pandemic baking obsession even inspired her new Biscuits & Banjos music festival, which showcases the similarly winding journeys of Black music and food.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring the pandemic, Giddens was collaborating with Italian musician Francesco Turrisi on the album They're Calling Me Home. "Francesco and I were thinking about the food that we couldn't get because we couldn't go home," said Giddens, who grew up in Greensboro, North Carolina. "For me, that turned into, 'How do I make biscuits?'"

Living in Ireland, Giddens had to rework basic elements of biscuit composition. How would Irish butter, with its higher fat content, impact the texture and rise? Which European flour would yield a comparable crumb? That's to say nothing of technique. "It turned into an obsession pretty quickly," she said.

World's Table

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

Giddens practiced until she arrived at a flawless variation with an adapted recipe from Southern Living magazine. First, she grates frozen Kerrygold butter into frozen, sifted White Lily flour (the colder the ingredients, the better). Next, she pours in thick buttermilk, and after a cursory stir, she dumps the wet mixture onto a heavily floured counter. "I start folding, turn, fold, turn, fold, turn, pat it out. I don't bother with a rolling pin," said Giddens. "I was doing four sets of folds, and then I threw in an extra one. The biscuits went poof."

Then comes cutting the dough – the womp – before she places the biscuits cheek-to-cheek on pre-cut parchment paper. Meanwhile, there's a sheet pan heating in the oven at 475F, a critical step that yields crispy bottoms. At first, Giddens confessed, she often underbaked her dough. Now, she checks how done it is after 12 to 15 minutes by gently pressing her fingers on top and jiggling a nascent biscuit; too much movement signals a gummy centre.

Karen Cox

Karen CoxGiddens' ideal biscuit has a certain flakiness. It's sturdy enough to hold bacon without crumbling, and tender enough to enjoy with jam. During the years it took her to master biscuit making, They're Calling Me Home won a Grammy Award for best folk album. She also composed and sang in Omar, an opera that earned the Pulitzer Prize, and played banjo and viola on Beyoncé's hit single, Texas Hold 'Em. Along the way, she started to see how biscuits integrated into her life's work of tracing the complex history of music.

"Food and music have similar cultural markers. Like food, music moves with people, and it changes as people move. So, it made sense to connect them," said Giddens. "Biscuits and banjos happen to be two of my obsessions."

The rise of US biscuits

Biscuits, like the banjo, have a complex lineage. Their roots lie in dry, twice-baked breads, or rusks, that the British called "bisquites" after the Latin phrase panis bicoctus, or "twice-baked bread". But in the American South, particularly in the hands of Black cooks, they became soft, leavened symbols of class, skill and Southern identity.

In the book The Biscuit: The History of a Very British Indulgence, Lizzie Collingham writes that biscuits were an "an indispensable tool of empire building". Indeed, these nonperishable breads sustained soldiers and sailors for millennia, and in the early 1600s, English settlers in Jamestown, Virginia, survived on a supply of biscuits brought from the motherland.

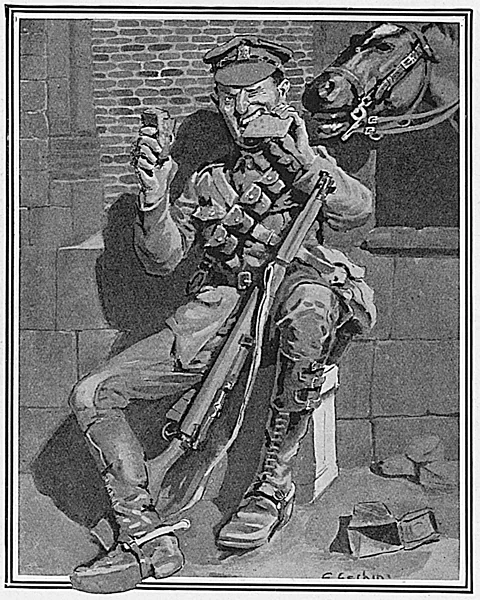

Alamy

AlamyA distinctly Southern biscuit began to emerge in the 18th Century. On Royal Navy ships, tough, dry biscuits had earned the nickname "purser's nuts". But in finer settings on both sides of the Atlantic, bakers added sugar, citrus and spices. The Virginia Housewife, an 1824 cookbook by Mary Randolph, includes a recipe for Tavern Biscuits, whose ingredients included flour, sugar, butter, mace, nutmeg, brandy and milk. It also shared a recipe for beaten biscuits.

"[Beaten biscuits] were the most common biscuit in the South," said Michael Twitty, a James Beard Award-winning food writer and historian. "The lore behind them is true. A Black child, normally a little boy, would sit there with the back of an axe or a club, and on a clean log, he would literally beat this dough over 1,000 times."

The thin, crunchy beaten biscuit closely resembled what Americans consider a cracker, but this violent, repetitive thrashing – only possible with enslaved labour – produced a slight rise and delicate crumb onto which diners would drape slices of country ham. White flour was still a luxury in the antebellum South, and beaten biscuits were an edible stamp of wealth.

"Biscuits have been a demarcation line in terms of class and race," said Toni Tipton-Martin, a food journalist and historian whose work includes the book The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. "African Americans have traditionally been known for making cornmeal and more coarse grain breads. Wheat flour was not available in early America, and it was an expression of affluence to be able to make biscuits."

Melanie Wilkerson

Melanie WilkersonHowever, it was chemical leavening agents that created the soft, layered Southern biscuit as we know it today. At first, bakers used saleratus (potassium bicarbonate) and soda (sodium bicarbonate). The buttermilk in Giddens' recipe dates to these early leavening agents, which required an acid to activate. Then in 1856, Eben Norton Horsford patented baking powder, officially giving rise to the poof of the Southern biscuit.

As milling technology improved in the late 19th Century, Southern-grown soft winter wheat, (which was better for so-called "quick breads" than sturdy loaves) gained popularity. When flour prices dropped, biscuits became a marker of social mobility across racial lines, transforming a Sunday treat into an everyday staple.

American food industrialised in the 20th Century, and so did biscuits. An unnamed Black cook for Pullman Company trains used a premade flour mix to produce biscuits on the fly; his work inspired Bisquick, the first commercial biscuit mix. In 1931, Lively Willoughby patented canned refrigerated biscuit dough. Biscuit diversity flourished, too, such as cathead biscuits and North Carolina's hoop cheese-filled variety. Bakers embraced efficient drop biscuits and airy angel biscuits, which use baking powder, baking soda and yeast.

Biscuits had transformed from a seafaring staple to a luxury good made by enslaved cooks to a food of the working class. Farmers and labourers carried biscuits slathered with jam or stacked with ham in their lunchpails. Twitty recalled a line from South Carolinean journalist Ben Roberston's memoir, Red Hills and Cotton: "To fry chickens, to boil coffee, to boil rice and to make good biscuits were the four requirements we demanded of cooks."

Zwelis

ZwelisThe year of Giddens' birth, biscuits broke into America's fast-food pantheon. In 1977, Bojangles, a fried chicken and biscuits counter, first opened in Charlotte, North Carolina; there are now 800 Bojangles across 17 states. The same year, a single location of Hardee's added ham and sausage biscuits to its breakfast menu. Across Hardee's franchises, workers bake more than 100 million biscuits annually. In the 1980s, Kentucky Fried Chicken and McDonalds took biscuits nationwide.

Buttered, dotted with blueberries, smothered in sausage gravy, split and sandwiched, biscuits had become wholly American without losing their Southern accent. "I see this food as graduated British, even if there's nothing like it in the British Isles, not even scones. You can't find them in Africa," said Twitty. "So they're this combination of all those different streams and elements that make America what it is."

Food and music as culture

With Biscuits & Banjos, Giddens wanted to create a festival that would build community and inspire cross-disciplinary collaboration, and the three-day event in Durham, North Carolina (25-27 April) brought together Black musicians, activists, historians and chefs. Her Grammy-winning band, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, reunited for the first time in a decade, performing songs from acclaimed African American fiddler Joe Thompson and guitarist Etta Baker. New Dangerfield, a Black string band of Giddens acolytes, played a sweet and earnest New Orleans waltz, while Niwel Tsumbu connected the musical traditions of his native Congo to the American South.

By day, festival-goers ate biscuits from restaurants on a downtown Durham biscuit trail and bought tote bags that read: "Well butter my butt and call me a biscuit". They also gathered in an armoury, which had held a square dance the night before, for a talk with Tipton-Martin, Twitty and Dr Cynthia Greenlee on biscuit history and the contributions of Black cooks to one of the US South's most iconic baked goods.

Anthony Mulcahy

Anthony MulcahyGiddens hopes to stage the festival again in Durham in 2026, creating a space where food and music continue to challenge narratives, uplift Black stories and contribute new ideas to storied traditions.

"Food and music are such a great way to talk about culture," says Giddens. "They're disarming. They're innocent. They are shaped by the forces around them, whether that's political or cultural. The more we can understand that, I think, the more we can understand ourselves."

Ingredients

2½ cups self-raising flour (I use White Lily Self Rising flour** that has been in the freezer)

113g (1 stick) unsalted butter (I use salted and Irish*), frozen overnight

1 cup buttermilk, chilled***

2 tsp butter, melted

* – Irish butter has a higher fat content and lower water count than American butter; French and Danish butter is similar. But you must make sure it's good and frozen because, by nature, it's softer and will melt faster when you handle it.

** – White Lily (a regional Southern flour made from soft red winter wheat) has a naturally lower amount of protein and therefore makes an exceptional biscuit. You aren't making biscuits for your health, but try to find the unbleached version.

*** – Make sure it's buttermilk that is just cultured milk and doesn't contain any fillers,

additives or gums. Nice thick buttermilk from local farms is the best.

Rhiannon Giddens' "They're Biscuits, Not Scones" recipe

Adapted from Southern Living magazine

Makes 10-12 biscuits

Method

Step 1

Measure a piece of parchment paper to fit your sheet pan; be sure to make it longer but exactly as wide, so you can use the overhang to lift the sheet when there are biscuits on top. Set aside.

Step 2

Sift the flour into a bowl, then grate in the frozen butter (I use a box grater, the large holes side). Toss together briefly (but no need to work the butter into the dough). Put in the freezer.

Step 3

While the bowl is in the freezer, preheat the oven to 475F. If you have an electric oven, put the pan in the oven and heat it up without the parchment paper. If you have a gas oven, you can keep the pan out of the oven and place the parchment paper in it. This is all in pursuit of nice crispy bottoms.

Step 4

Make a well in the middle of the butter/flour mixture and pour in the buttermilk. Always have more on hand in case you need it – I usually have to add a bit. Stir until it starts to come together. It should be pretty sticky and a bit wet. Turn it out onto a well-floured surface and pat it into a rectangle (you can use a rolling pin if it helps).

Step 5

Fold the dough in thirds like a letter and flatten out, then turn and do it again in the other direction. Do this whole process at least once more, for a total of 4 sets of folds. This is what takes the most experience; you’ll eventually learn how much handling is enough. Aim for handling less, not more.

Step 6

Roll or pat out and start cutting your biscuits; use a biscuit cutter or a glass and be careful not to twist (that is a myth that will end up actually curtailing your biscuit's rise). If the dough is in that sweet spot of not too wet but not too worked, the cutter will not stick to the dough, and if it's a glass it will make a nice little "womp" sound.

Step 7

Place the biscuits on the parchment paper in a honeycomb pattern so that there are no spaces. This will help the biscuits rise. If you like biscuits that are crispy all around and not as tall, you can place them with space around them or only touching on the sides.

Step 8

Move the biscuit-laden parchment with the overhang onto the pan, this will take practice. You may brush melted butter on top of the biscuits at this point.

Step 9

Bake at 475F for 12-15 minutes until lightly browned. You can feel they are done by shaking one with your fingertip on top; if they are too moveable, they aren't quite set.

Step 10

Place them in a basket lined with a tea towel and cover; they will stay nice and moist this way. Put the leftovers straight into the fridge to be reheated in the oven when ready.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.