An ancient oasis in China’s remote desert

Asia File/Alamy Stock Photo

Asia File/Alamy Stock PhotoAlthough not as widely known as the Great Wall, the karez – and its vast maze of underground tunnels – is one of China’s most recognized ancient engineering feats.

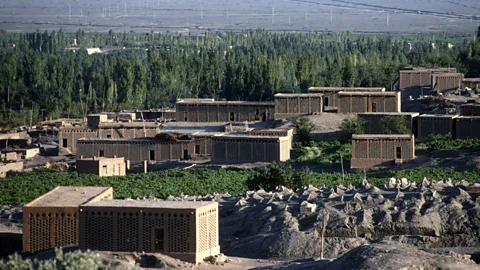

The air here has a matte gold colour, a reflection of the rugged, desert landscape. Far on the horizon, the peaks of the Tianshan Mountains shimmer, while in the foreground, China’s Turpan Basin is dotted with chunches, the Uyghur name for the small, square buildings where grapes are dried.

Despite the harsh climate, the Turpan soil is fertile and vineyards flourish throughout the area. More than a dozen different types of grapes are grown here, and the water the grapes need to grow is brought to their vines by an ancient irrigation system called the karez, or ‘well’, in the Uyghur language.

Reza/Getty Images

Reza/Getty ImagesAlthough not as widely known as the Great Wall, the karez is one of China’s most recognized ancient engineering feats. Constructed by the Uyghur people who long ago settled this remote part of northwest China, the system once carried water throughout all of what is now the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Powered only by gravity, the irrigation method carries glacial groundwater to the Turpan Basin from the eastern base of the Tianshan Mountains. To avoid evaporation in the burning summer sun, the water streams through a maze of underground tunnels that connect more than one thousand wells across the area. Each individual tunnel stretches anywhere from three to 30km.

At its peak in 1784, the karez spanned 5,272km, with 1,237km running through the basin. The water flowed directly to the farms and vineyards, while residents drew cool, crisp drinking water from one of 172,367 wells.

Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty Images

Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty ImagesA similar system – called the qanat – had been built a century earlier in Persia. It is believed that traders from what are now Iraq, Iran and Kurdistan brought their engineering knowledge to the western part of China, before continuing east along the Silk Road.

After the development of the karez, the Turpan Basin became an oasis along the ancient trade route. With access to the karez, communities in the Turpan Basin flourished.

When I arrived at the Turpan train station, I hired a local guide, Ahmat. Like other members of Turpan’s Uyghur population, Ahmat is proud of his Chinese and Turkish heritage, which is reflected in the region’s historical sites, like the 3rd-Century Thousand Buddha Caves in Bozkrik and Tuyoq, an ancient Muslim pilgrimage site located just outside the village of Turpan.

Asia File/Alamy Stock Photo

Asia File/Alamy Stock Photo“Buddha's followers looked for a quiet place to meditate, which brought them to these mountains,” Ahmat explained.

However, the karez is arguably the most essential historical site in this remote region. But global warming and the industrialization of the region over the past several centuries has caused the mountain glaciers to melt more quickly and the water to evaporate.

“The drought is something of recent centuries,” said Ahmat. “A thousand years ago, the Taklimakan – the desert – wasn't here. It is not mentioned by the famous writers of that time.”

Meanwhile, high demand for water from an increasing number of factories has further strained the region’s resources.

Asia File/Alamy Stock Photo

Asia File/Alamy Stock PhotoWhat’s left of the ancient karez remains a lifeline for the Uyghur people, who contend with freezing cold winters and almost unbearably hot summers. Without the underground canals, life here would be impossible. Grape vines, apricot trees, cotton and melons would not grow. Pipes bringing in water from outside the desert could be a solution. But where the government already replaced the karez with pipes, residents claim the water doesn't taste the same as the naturally filtered water.

Instead, motivated by the site’s potential to become a Unesco World Heritage Site, the Chinese government has devoted 45 million yuan to protect the ancient irrigation system. Since 2009, more than 600km of tunnels have been cleared of silt, and many of the crumbling wells have been repaired.

Reza/Getty Images

Reza/Getty ImagesAfter driving all day through the surreal landscape, Ahmat and I stopped to purchase a bag of Turpan’s famous dried grapes for 10 yuan. They’re surprisingly juicy and noticeably more sugary than other raisins I’ve tried – the product of the extreme desert heat, the basin’s low altitude and the 40-day drying process.

Today, Turpan is the world’s largest producer of green raisins. But there was something about eating them here, as cool mountain water coursed through ancient tunnels below my feet, that made them taste especially sweet.

Join over three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.