Africa’s path less sailed

The 50-year-old MV Umoja that crosses Lake Victoria operates on no set schedule, offering a nostalgic look back at the way travel used to be – painfully, delightfully slow.

Another hour passed and the engines remained silent. The other passengers lay on their bunks, swatting away flies. A crewman squatted patiently at the stern, fingers steepled into a visor to shield his eyes from the fierce sun. Only the birds seemed anything but listless: swifts chuckled around the papyrus reeds that line the bay; a marabou stork picked through the flotsam that lined the wharves. The dockyard shimmered.

“Maybe at 4pm,” said Kennedy, the engineer, with a resigned shrug.

I began to wonder if we would ever leave.

Lapping languidly at the boat beneath my feet was Lake Victoria, the world’s second biggest freshwater lake and the body of water I’d been hoping to cross for the last three days. It used to be that many ferries criss-crossed the lake, making the 320km journey between Uganda and Tanzania. But decades of accidents and mismanagement had reduced my crossing options to one: the MV Umoja, a 50-year-old Glasgow-built cargo-ship, one in a long line of tireless motor vessels that ply the coasts and channels of Africa’s Great Lakes.

From my vantage point, standing on the quarterdeck, surrounded by Equatorial decay, the Umoja seemed a floating relic. But for people bent on travelling from Kampala, the Ugandan capital, to Mwanza, Tanzania’s second-largest city, it offered a beguiling alternative to the 870km overland journey on a series of packed minibuses. By contrast, I’d heard, the ship voyage was calm and civilized, a nostalgic reminder of the way travel used to be. It was also said to be slow – and exactly how slow was becoming increasingly clear.

“It sometimes seems as though Africa is a place you go to wait,” Paul Theroux wrote in Dark Star Safari, the 2002 travelogue that had indirectly led me to this point. Theroux had stood where I was now, mid-way through the voyage that would form the basis of the book featuring travel writing’s great curmudgeon traversing the African continent by rail, bus and, in this case, very slow boat.

For Theroux, the Lake Victoria crossing embodied the simple pleasure of independent travel. “Here as elsewhere I was the only mzungu traveller,” he wrote (mzungu is a Swahili word used to refer to a white person). “The others stuck to selected routes and travelled in groups, to look at animals… And yet, though I was solitary, all I heard was karibu [welcome].”

Keen to follow Theroux’s lead, I’d quickly discovered that the Umoja doesn’t run on any set schedule. Acting on the ambivalent advice of a hostel receptionist in Kampala, I made my first foray to Port Bell, Kampala’s lakeshore harbour, and found only an empty berth, and no clue from people I spoke with as to when the Umoja would arrive. I returned twice the next day. Still nothing.

In the end, it would be two days – and several fruitless motorcycle taxi trips up and down the Port Bell road – before an idle dockworker pointed promisingly toward the water. There she was – finally – a white-hulled, 90m-long ship with empty cargo bays at each end and two steep stairways leading to living quarters.

I asked the first person I came to, a rangy-looking man sitting on a crate at the boat’s stern, about passage.

Yes, said the man, who identified himself only as Kennedy. I could travel to Mwanza.

“And when does it leave?”

“Maybe 11,” he said, almost as though it were a question. “Come down tomorrow at 10. You can have my cabin.”

The price? 30,000 Ugandan Shillings, with the bed thrown in. It was a bargain for me; a great windfall, one suspected, for him.

I wasn’t wholly convinced by this promise. Transporting passengers, after all, is not the MV Umoja’s official function. It’s more of an ad hoc service that evolved to fill a gap in the market. Yet the next morning, down at the dock I found a man at a desk to stamp me out of Uganda, waving me off with a “thank you for visiting”. I bunged a handful of Ugandan shillings to a supine fellow in a quayside portacabin and stepped aboard, following Kennedy’s lead up a stairway and into a starboard-side cabin. The brass-plate above the door was engraved with the words “Second Engineer”.

I suspected the room inside had changed little since the ship’s debut in 1965. I found it appointed with a timber-framed single berth, a washbasin, a writing desk and small transistor radio tuned to a pair of basso African voices debating the latest European football news. I dumped my bag, flopped down on a cushioned bench by the wall and settled in.

“This was harmony, privacy and the sort of seedy comfort I craved,” I recalled from Theroux’s book. Like him, I didn’t care if the crossing took two days or 20.

By late the following afternoon, we hadn’t budged an inch. Kennedy’s 11am departure time had come and gone with barely a grumble from passengers or crew. The hold up, Kennedy said, was due to the late arrival of the ship’s principle cargo, four lorryloads of maize sacks – World Food Program aid that was now being piled onto the loading bay by muscle-bound stevedores.

We were facing the sort of never-ending delay that would have provoked universal apoplexy back home in London. But here, no one on board seemed remotely flustered. While the crewmen sat in the galley eating meat stew with fistfuls of ugali, a maize porridge, the passengers congregated along a handrail overlooking the action. Most were Tanzanian families heading home; others were Ugandan banana traders – the fruit they were exporting lay in green clusters beneath the life-boats. The only other mzungu travellers on board were two young Floridians who had been prompted to seek passage because they’d read about the journey in a guidebook and “figured it would be cool”. “We were never much for flying,” said Charles, who together with friend Cory were headed for a Peace Corps mission. “Besides, who wouldn’t want to take a freighter across Lake Victoria?”

Our postponed departure had left ample time for an additional million or so other wayfarers to smuggle themselves aboard. Sea-flies, harmless mosquito-sized insects, now squatted on every surface, stupefied into stillness by the gathering heat of the afternoon. And yet, the prevailing atmosphere among the passengers was one of optimism, thanks to the short-term solidarity that sometimes accompanies long-distance travel. There was laughter and shared food, bottles of Nile Gold bought from the makeshift stalls in the dockyard – in Swahili, Umoja means “unity”.

Suddenly, there was a flurry of activity: the maize lorries, now disgorged, rumbled back onto the jetty; oddly, the smashed-up front half of a Toyota HiLux was hauled aboard. And then the deck began to shake as the old engines kicked into gear; men hurried to release the mooring ropes. Finally, at around 5pm, 30 hours after our expected departure, we chugged out of port, past the lonely outcrop of Bulingugwe Island and into Murchison Bay.

Six hours later, in the dead of night, I awoke in my cabin to the ship’s roll and electric blue flashes illuminating the window. A small puff of sea-flies took off about my head. Outside, a storm was strobing across the port bow, intermittently illuminating our surroundings – no land in any direction, just the all-encompassing water of an inland sea.

This was disconcerting, not least because the lake’s maritime history was littered with massive disasters. In the most catastrophic of all, the MV Bukoba foundered in 1996, leading to the drowning of as many as 1,000 souls. Little wonder that passenger ferry services had been suspended here. By contrast, the Umoja seemed defiant and dogged, a lone survivor sailing a route she’d travelled 10,000 times before.

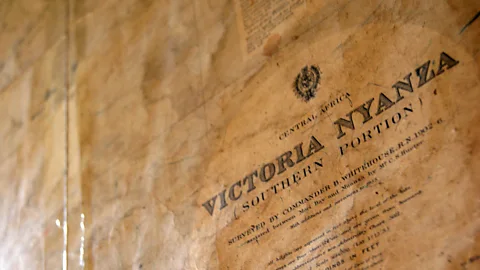

In the morning I set out to explore. I snooped through the clamorous engine bay, then up to the navigation room, a time capsule of antique equipment and yellowing, colonial-era maps captioned with the words, “Surveyed by Commander B Whitehouse, 1902-6”. Up on the bridge, a young pilot sat on a stool at the helm, casually steering with one hand on the wheel. He nodded hello before returning his gaze to the empty horizon. All of the crewmembers seemed happy to have me up here on the bridge enjoying the view as the Umoja serenely ate up the remaining miles.

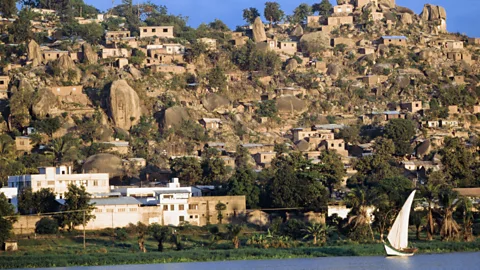

Sometime around mid-afternoon, the faint silhouette of Tanzania’s shoreline began to appear in the distance. The boulders that line the shore of Mwanza grew ever bigger beyond the gunwales. I savoured the simple joy of forward progress, and thanked Theroux for showing me the way.

“As African time passed,” the author wrote, “I surmised that the pace of Western countries was insane, that the speed of modern technology accomplished nothing, and that because Africa was going its own way for its own reasons, it was a refuge and a resting-place, the last territory to light out for.”

A refuge. As we pulled up to Mwanza’s dilapidated dock, it struck me as a fitting way to describe the Umoja. So what if we arrived two days later than planned? So what if I was about to discover that the train I’d hoped to catch across Tanzania hadn’t run in six months? I shouldered my bag, walked down the gangplank and stepped onto Tanzanian soil in no hurry at all.