Why are orcas suddenly ramming boats?

Getty Images

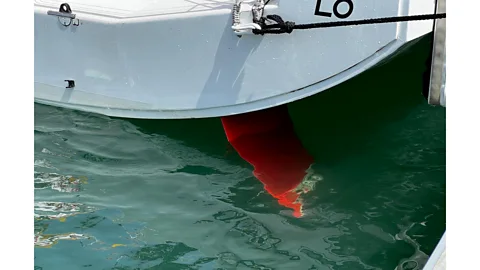

Getty ImagesA group of Iberian orcas have a risky new hobby: chasing sailboats and breaking their rudders. Now scientists are finding out what's really behind the fad.

In the summer of 2022, Andrea Fantini and his crew mates were sailing towards Tangier on the Moroccan coast at the start of a global regatta, the Globe40 race, when one of them suddenly shouted: "Orca! Orca!"

Fantini saw a tail in the distance, and then a huge orca rushing straight towards them. "We saw the first orca coming, then the second, then the third, and then we were surrounded by orcas," he recalls. "There were seven orcas all around us, and they started to attack the rudder. It was super weird, and a bit scary."

Orcas are commonly known as killer whales but are actually part of the dolphin family, and have never been known to be aggressive towards humans in the wild. Since 2020, however, the strange new behaviour of a group of them living in the waters around the Iberian Peninsula, in south-western Europe, has been baffling sailors, scientists and now a global audience. The cetaceans appear to have invented a risky new game: It involves chasing sailboats and pushing the rudders, breaking them in the process. (Read more about some of the incidents in the Atlantic in this special report by Victoria Gill.)

Last week, it was widely reported that an orca had rammed a boat in the North Sea. A few days ago an orca pod "attacked" racing boats near the Strait of Gibraltar. Scientists prefer to call these clashes "interactions", since the orcas' intention may be playful rather than hostile (more on this later).

It's an unprecedented phenomenon, says Alfredo López Fernández, an orca researcher at the Atlantic Orca Working Group (GTOA), which is monitoring the Iberian orcas. Historically, there have been some reports of orcas diving under boats, or slamming into them and causing them to sink. But López says those cases tended to be isolated and tied to a specific situation: "None of them is similar to what's happening now."

The new behaviour sees the orca touching, pushing and even pivoting boats, according to an analysis of the interactions reported in 2020. López cautions that our own perception of this may be biased. What feels like a ramming may just be the orca moving the boat or rudder with their heads and bodies "because they cannot hold things with their fingers".

A new, ongoing research project by orca specialist Renaud de Stephanis, which involves presenting the wild orcas with dummy rudders and filming them, has revealed fresh insights into these encounters. What appears to be going on is rather than biting the rudders, the orca are pushing them with their noses until they break.

"They're pushing, pushing, pushing – boom! It's a game. Imagine a kid of 6, 7 years, with a weight of three tonnes. That's it, nothing less, nothing more," de Stephanis tells the BBC. "If they wanted to wreck the boat, they would break it in 10 minutes' time." He has been studying Iberian orcas since the 1990s and is the coordinator and president of Conservation, Information and Research on Cetaceans (CIRCE), a marine conservation organisation.

The game appears to be spreading. In 2022, there were 207 interactions, data from the working group showed, up from 197 in 2021, and 52 in 2020. Originally, they mostly happened in and around the Strait of Gibraltar, along the coasts of Portugal, Spain and Gibraltar, but the playing field has widened to include the coasts of Morocco and France. "The interactions follow the orcas' migratory routes," says López.

Only about 35 Iberian orcas have been identified, and the total population is thought to number fewer than 50. Of those, 15 are known to be involved in the boat encounters – it's always the same group, says López.

According to the Cruising Association, three yachts were sunk in 2022 and 2023 after orca interactions. As Fantini says, breaking the rudder completely can open a hole, and water can rush in, sinking the boat. Even those sailing in sturdy racing boats, with back-up rudders and rescue services close by, can find the experience frightening.

"20 minutes ago we got hit by some orcas," says Jelmer van Beek, the skipper of Dutch sailing team JAJO, in a video filmed this summer in the Atlantic Ocean to the west of Gibraltar, during a leg of The Ocean Race. "Three orcas came at us, straight at us, and they started hitting the rudder. Impressive to see the orcas, first of all, beautiful animals, but also a dangerous moment for us and the team."

In Fantini's encounter during last year's Globe40 Race, the team's underwater camera captured the orcas swimming towards the rudder. "It seems that they really have a modus operandi, they have a project, they know what to do. They were really well organised," he says.

As part of a project supported by CIRCE and Spain's Ministry of the Environment, Renaud de Stephanis has been intensely monitoring this group of orcas. He and his team have used a multitude of cameras – underwater, above the water, and even attached to the orca – to understand exactly what's going on between them, and the dummy rudders. "We discovered what happens, the killer whales push the rudder with their nose, this makes the rudder break by leverage," he says. The detailed results are not released yet, but he is hoping to share them publicly soon.

Masa Suzuki and Andrea Fantini

Masa Suzuki and Andrea FantiniWhat started this game? And what can be done to stop it?

In the fourth summer since the trend began, the mystery has still not been fully solved – but scientists are starting to get there. Here's what we know.

Even before 2020, the orca communities in and around the Strait of Gibraltar had developed a feeding strategy that involved swimming up to tuna fishing boats to snatch the hooked fish from the lines. In 2020, nine orcas began approaching sailboats, pushing or bumping them, and at times, breaking the rudder. There were three "ringleaders" who were most involved in these interactions: an adult orca called White Gladis, and two young ones, Black Gladis and Grey Gladis. (Scientists chose a name for all interacting orcas: "gladis", based on one of the species' old names, "orca gladiator"). Over the years, more orcas have joined them. They have consistently focused on sailboats, rather than all types of boats, López says.

López cautions against describing the behaviour as attacks: "They are being judged socially before we even understand what they're doing."

In his view, their intention is not hostile. "The orcas are not showing an aggressive attitude in all of this, even though they may break something," he tells the BBC in an email. "We know that it's a complex behaviour that has nothing to do with aggression (they don't want to eat anyone, nor harm humans) nor revenge (orcas are not resentful)."

Once the rudder is broken, the orcas swim away – as they did in the case of Fantini, whose boat had two rudders: "Luckily, they broke just one. And then they went away. They disappeared," Fantini says.

This leads to the trickiest question: what exactly is their motivation?

Masa Suzuki and Andrea Fantini

Masa Suzuki and Andrea FantiniThe working group has come up with two hypotheses, according to López.

One might be called the "fun or fashion hypothesis". As López puts it, it's the idea that the orcas "have invented something new and are repeating it". This behaviour would be more typical of young orcas, he says. In a 2021 report, the working group notes that young orcas have occasionally they have been observed approaching ships, peering at them, following their wakes and jumping on the waves they cause.

The other might be called the "trauma hypothesis". According to this explanation, "one or more individuals had a bad experience and are trying to stop the boat in order to prevent a recurrence", he says. In his view, this would be more in line with adult orca behaviour.

"We don't know which one of these is correct, and even if it's the second one, we don't know what might have been the triggering event," says López. However, he lists a few points that support the second, trauma-related explanation.

Firstly, White Gladis, an adult, was probably the one who started the interactions. At the time, in 2020, she was the only adult who did this, amid a group of young orcas. Secondly, in 2021 she continued the interactions even though she had her newborn daughter with her, which in his view suggests that "her drive to interact is even stronger than her protective maternal instinct".

As for what this traumatising experience might have been, he points out that many fishing boats put their lines out at the stern of the boat, which attracts orcas, who come to inspect the lines and snap up some fish. There have been cases of orcas getting tangled in and injured by these lines. It's possible that something like this happened to White Gladis, he believes. Meanwhile, Black Gladis had injuries that may have been caused by humans, and "we know that Grey Gladis witnessed a friend getting tangled in fishing lines in 2018", says López.

"All of this makes us think that human activities are at the origin of these behaviours, even if it's in an indirect way," says López. What we can learn from their new habit is "that they are very intelligent, and that we are bothering them a lot".

Lori Marino, a neuroscientist, cetacean expert and president of the Whale Sanctuary Project, says the "fun" theory makes the most sense to her. "These are highly intelligent and inquisitive animals and they seem to be attracted to the underside of the boats and parts that are sticking out. Orcas are cultural beings and they often will start a fad and that fad will spread through the group."

Such cultural traditions include distinctive call types, which have been described as dialects, as well as different feeding strategies.

These different behaviours "all start as fads", says Marino. "The fad, if it continues, can become part of their culture and be passed down from one generation to the next," she says. Their ability to work in groups helps develop such complex fashions and traditions: "For instance, they may coordinate their behaviour to wash a seal off an ice floe or enter into different defensive swimming patterns if being chased by a predator… So the capability is there. Orcas show impressive levels of organisation in many other activities," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSailors and orca experts agree that it would be best for the risky trend to stop. But how?

Unfortunately, there doesn't seem to be a sure-fire way of preventing or even shortening the interactions. The Orca Working Group recommends avoiding the orcas by checking regularly updated maps of their movements. Renaud de Stephanis' top recommendation is also to avoid the areas where the orcas are, with the help of updated maps based on satellite-tracking the orcas – this is starting to help reduce the interactions, he says. Sailors have also tried scaring them away by banging things. However, this doesn't seem to make much of a difference.

Trying to escape them is futile. According to the working group's 2021 report, orcas usually swim at speeds between 8-11 knots but can reach speeds of up to 29 knots, making them hard to shake off (the boat sailed by Team JAJO, the Dutch team, was doing 12 knots when the orcas struck, and according to the sailors, the animals seemed to find the speed exciting). There is no evidence that other tricks used by some sailors, such as pouring sand on orcas to confuse them, work – and throwing things at them is not a good idea given that Iberian orcas are endangered.

Leaving the area quickly helps, says de Stephanis (not because one can out-speed an orca, but because they are less likely to follow the boat once it's outside their preferred area).

In Fantini's case, the orcas stayed for around 30 or 40 minutes: "It felt like forever." The team waited until the orcas had broken the rudder and left. They knew there was no point trying to speed away: "They were very fast. Even if you try to go as fast as you can with the boat, they will always be faster. So going fast is not a solution. I don't actually know what the solution would be. Right now, If I have to go again, I don't know what to do." He laughs. "Except to bring a spare rudder."

--