Los Angeles: Why tens of thousands of people sleep rough

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLos Angeles is known worldwide as a city of glamour but on a visit this week, US President Donald Trump said its growing homelessness problem could "destroy" it. So how did LA end up in this situation?

What is the scale of the problem?

You do not have to walk far in Los Angeles to see people sleeping rough. Many spend their nights in temporary shelters, or other places not meant for human habitation - on the street, in an abandoned building, or a transport hub.

The number of homeless people in Los Angeles has grown by 33% over the past four years. Every night, nearly 60,000 Los Angeles County residents are homeless, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority has found.

A total of 85% of Los Angeles's homeless people are adults without children, 70% are male, and 44% are black, even though they account for only 8% of Los Angeles residents.

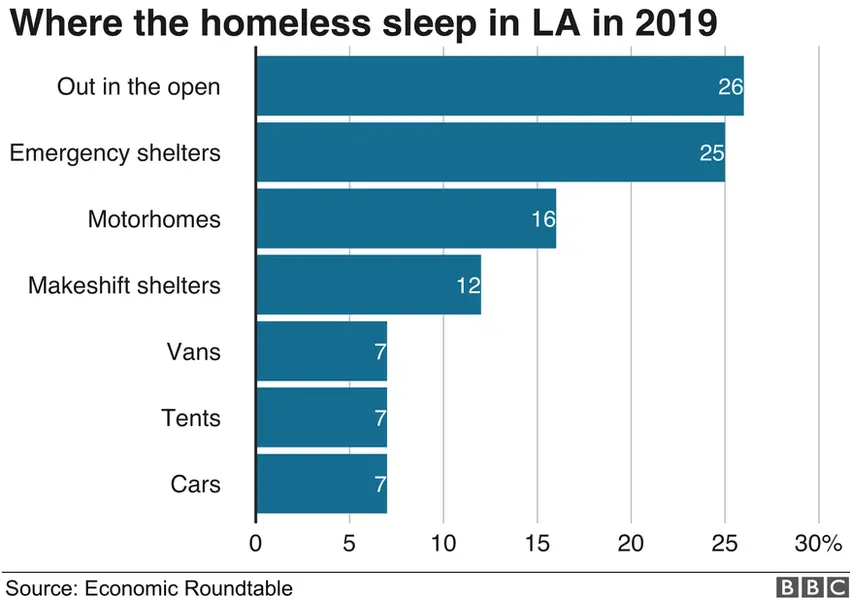

And Los Angeles has the largest number in the United States of homeless people who do not sleep in emergency shelters:

- a fifth sleep in tents and makeshift shelters

- a quarter sleep in the open

- 30% sleep in vehicles that are often decrepit and inoperable

What are the key causes?

Money is at the root of the city's homeless crisis - jobs that pay too little and housing that costs too much. Half of homeless people say they do not have housing because they lost their jobs and cannot pay rent.

Only 21% of new homeless people in the city report having a mental disability compared with 55% of those who have been homeless for longer, suggesting rates of mental illness go up as people are homeless for longer.

Blue-collar workers in Los Angeles were able to earn middle-class wages and buy homes until the Cold War ended, nearly 30 years ago. The government cutting back on military expenditure meant the national defence industry, which was centred in Los Angeles, shrank by more than half.

Well paid jobs were replaced by minimum-wage jobs.

Little new housing - especially lower-cost rental housing - has been built over the past 30 years, even though Los Angeles's population has grown by 15%.

The result has been steady rent increases that have made housing unaffordable for many working-poor families.

Only a small percentage of housing is subsidised by government. The vast majority of rental housing is privately owned and rents are set at the free-market rate.

More than 780,000 people in Los Angeles spend more than 90% of their income on rent - and these precariously housed individuals are at high risk of homelessness.

What is Skid Row?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHomeless people are now seen in nearly all neighbourhoods and business districts throughout Los Angeles. This was not the case a decade ago, when most of the homeless population was contained in an area known as Skid Row.

Skid Row is still a 1-sq-km (250-acre) area located only 500m east of City Hall, although it is no longer as tightly contained as it used to be.

In 1976, city officials established Skid Row as an unofficial "containment zone", where homeless people, shelters and services would be tolerated. As a result, most visitors to the parts of Los Angeles that attracted visitors from around the world never saw a homeless person.

The recession of 1981 saw soaring unemployment and the beginning of the crack cocaine epidemic in Los Angeles. The number of homeless people in Skid Row grew beyond the capacity of shelters and even the streets to accommodate them. Many moved to other areas but generally ones out of view of the police.

Outside Skid Row, police vigorously enforced the city's laws, making it a criminal offence to sit, lie down or sleep in a public space.

Subsequent recessions and the ongoing loss of unskilled jobs spurred continuing growth in homelessness.

What is happening elsewhere in the US?

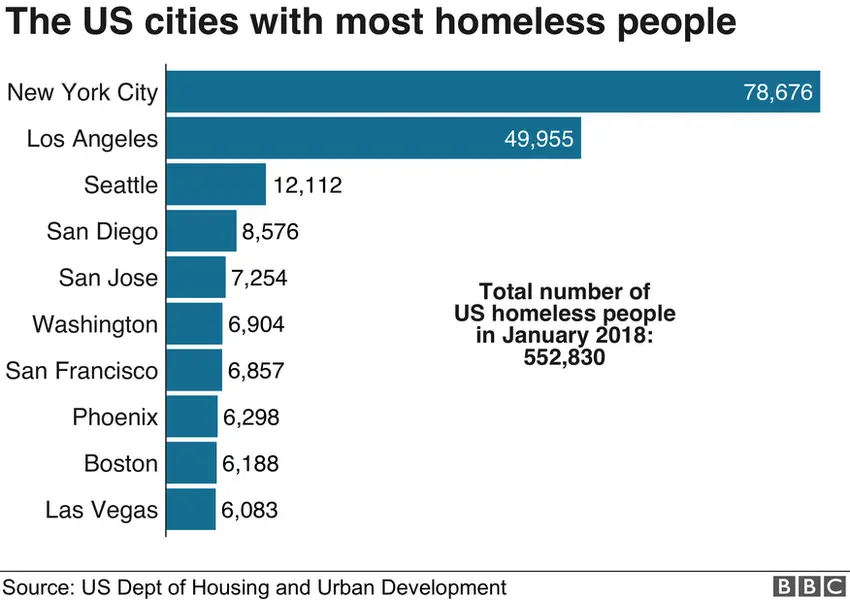

Although New York has more homeless people, it is the number not in emergency shelters that makes Los Angeles stand out. Only about one in seven homeless adults in Los Angeles has access to a temporary shelter bed - and one-fifth of all unsheltered homeless people in the United States live in Los Angeles County.

Other major US cities have fewer homeless people on the streets because they provide more housing. For example in Boston, only 3% of homeless people are unsheltered and in New York only 5%.

How do the people of Los Angeles feel about homelessness?

The reaction of housed Angelenos has been mixed. On the one hand, in 2016 and 2017, voters overwhelmingly approved new taxes to pay for more housing and services for unhoused people. But there have been few visible signs of progress since then, in part because of homeowners not wanting homeless housing or services anywhere in their communities.

One of the tax measures approved by voters provided $1.2bn (£964m) to build 10,000 housing units for homeless people. However, recent projections indicate it may be enough for only 7,000. Meanwhile, homelessness has continued to grow and both housed and unhoused residents are expressing frustration and anger.

Organisations that serve homeless people are urging the public to be patient and to recognise housing and services need to be provided in every community.

However, both the city and county of Los Angeles are considering legal measures to drastically limit where people can sleep to avoid arrest. Those working on behalf of homeless people say this would remove the only protection they have.

An approach supported by both supporters of homeless people and labour unions is to address homelessness as an income problem rather than only a housing-supply problem and to provide jobs for employable adults.

Work is being done to identify adults who will become long-term homeless. And they are given housing and trained for jobs that are held open for them.

Los Angeles's spike in homelessness has been years in the making. The question is how quickly this tide can be turned and how.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for outside organisations.

Daniel Flaming is president at non-profit research organisation Economic Roundtable. You can follow him on Twitter.

Gary Blasi is professor of law emeritus at UCLA Law School.

Edited by Ian Westbrook